You’ve seen them in every doctor's office. Those glossy posters of a flayed human, skinless and maroon, looking like a weirdly fit anatomical nightmare. Most people glance at a diagram of body muscles and think, "Okay, cool, there’s my bicep, there’s my six-pack."

It’s actually way more complicated. Honestly, most diagrams are kinda lying to you. They show muscles as these isolated, distinct rubber bands. In reality? Your body is a messy, interconnected web of fascia and overlapping fibers. If you’re looking at a map of your muscles to fix a back ache or get stronger, you’ve gotta look past the surface-level drawings.

The Problem With Your Standard Diagram of Body Muscles

Most anatomical charts are based on the "average" human. But here’s the kicker: humans are anatomically diverse. For example, some people are born without a muscle called the palmaris longus in their forearm. Seriously. If you touch your thumb to your pinky and tilt your wrist back, and you don't see a tendon pop up in the middle? You’re one of the 14% who just doesn't have it.

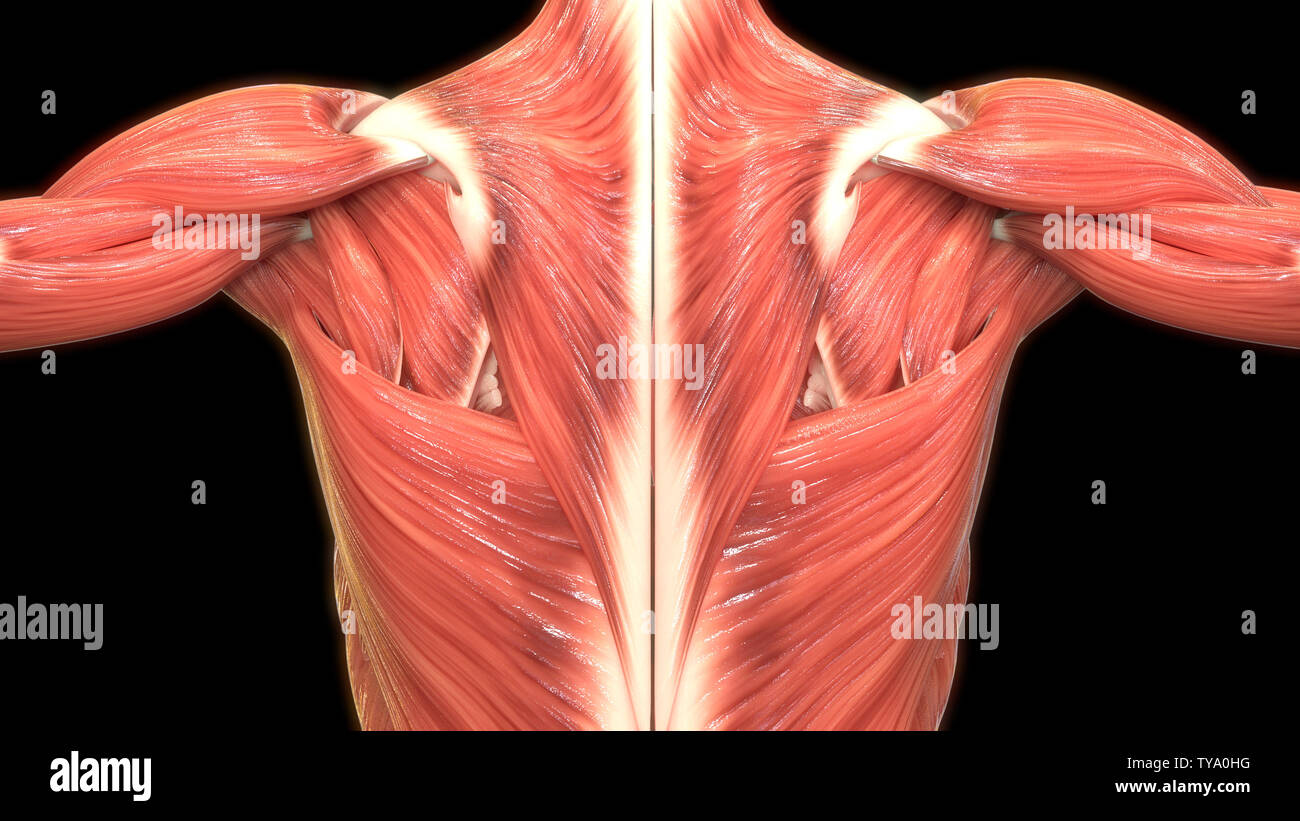

A standard diagram of body muscles won't tell you that. It also won't show you how muscles actually look in 3D. They aren't flat. They wrap. The latissimus dorsi—the big "wing" muscle in your back—actually twists as it attaches to your arm bone (the humerus). It’s a spiral, not a straight line.

When you look at a diagram, you're seeing a snapshot. It’s static. But muscles are never static. Even as you sit here reading this, tiny motor units in your postural muscles are firing just to keep your head from flopping onto your chest.

Why the Posterior View Matters More Than You Think

Everyone loves the front view. Mirror muscles. Pecs, abs, quads. But the "posterior chain"—the stuff on the back of the diagram—is where the real magic happens.

Take the gluteus maximus. It’s the largest muscle in the human body. On a diagram of body muscles, it looks like a big fleshy slab. But its fibers run diagonally. This allows it to stabilize your pelvis while you walk. If that muscle stops firing correctly because you've been sitting on it for eight hours a day, your lower back (the erector spinae) starts trying to do its job.

That’s how "gluteal amnesia" happens. Your brain literally forgets how to efficiently signal the glutes, so it overloads the small muscles in your spine. Look at the diagram again. See those tiny muscles snaking between the vertebrae? They aren't meant to lift heavy grocery bags. Your glutes are.

🔗 Read more: Exercises to Get Big Boobs: What Actually Works and the Anatomy Most People Ignore

Deep vs. Superficial: The Layers Most People Miss

The muscle diagrams you see on Google Images usually only show the "superficial" layer. That’s the stuff right under the skin.

But there’s a whole world underneath.

- The Transverse Abdominis: This is your "inner corset." It’s buried under your rectus abdominis (the six-pack). You can’t see it on a surface diagram, but it’s the most important muscle for spine health. It wraps horizontally around your midsection.

- The Multifidus: These are tiny, finger-like muscles that live deep against the spine. They are responsible for "proprioception"—telling your brain where your back is in space.

- The Psoas: This one is a nightmare for office workers. It connects your lower spine to your thigh bone. It’s the only muscle that connects your upper body to your lower body directly.

If you only look at the top layer of a diagram of body muscles, you’re missing the engine room. It’s like looking at the paint job of a car and trying to figure out why the transmission is slipping.

The Myth of Isolated Muscle Work

Bodybuilding popularized the idea that we can isolate one specific muscle. "Today is bicep day." "Tomorrow is calf day."

Biologically? That's kinda nonsense.

Your body operates in "slings." The Anterior Oblique Sling, for instance, connects your internal oblique on one side to the opposite adductor (inner thigh) via fascia. When you walk, these muscles work together to rotate your torso and swing your leg. A diagram of body muscles usually shows them as separate entities with different names, which makes us think they act alone.

They don't.

💡 You might also like: Products With Red 40: What Most People Get Wrong

Dr. Thomas Myers, the author of Anatomy Trains, revolutionized this thinking. He showed that muscles are essentially just "pockets" within a single continuous sheet of fascia. If you pull the "string" in your foot (the plantar fascia), it can actually create tension all the way up your hamstrings and into your neck.

How to Actually Use an Anatomy Chart for Training

If you’re using a diagram of body muscles to improve your gym routine, stop looking at the names. Look at the fiber direction.

Muscles can only pull; they can't push. They pull in the direction the fibers run.

Take the chest. The pectoralis major isn't just one big hunk of meat. The upper fibers (clavicular head) run diagonally upward. The lower fibers run straight across or slightly downward. If you want to grow your upper chest, you have to move your arm in the direction those specific fibers run.

- For upper pecs: Move your arm across your body and upward (like an incline press).

- For mid pecs: Move your arm straight across (like a flat bench).

- For lower pecs: Move your arm downward (like a dip).

It’s basic geometry. But if you just stare at a static diagram without understanding fiber orientation, you're just guessing.

The Often-Ignored Lower Leg

Most diagrams show the "calf" as one thing: the gastrocnemius. That’s the heart-shaped muscle that pops out when you wear heels or sprint.

But tucked underneath is the soleus.

📖 Related: Why Sometimes You Just Need a Hug: The Real Science of Physical Touch

The soleus is a powerhouse. It’s mostly slow-twitch fibers, meaning it’s built for endurance. While the gastrocnemius helps you jump, the soleus keeps you standing for hours. Fascinatingly, the soleus is often called the "second heart" because its contractions help pump venous blood from your legs back up to your chest.

If you're looking at a diagram of body muscles because your shins hurt, don't just look at the calf. Look at the tibialis anterior—the strip of muscle on the front of your shin. Most people have incredibly weak "tibs" because we never train the movement of pulling our toes toward our shins. This imbalance is a leading cause of shin splints.

Real-World Application: Assessing Your Own Map

The next time you see a diagram of body muscles, don't just memorize the Latin names like sternocleidomastoid or sartorius. Instead, try to visualize the layers.

Think about the muscles you can't see.

Think about the diaphragm. It’s a dome-shaped muscle sitting right under your ribs. It’s the primary muscle of respiration. Most of us are "chest breathers," meaning we use our neck muscles (scalenes) to suck in air. That’s why your neck feels tight after a stressful day. Your neck is trying to do the diaphragm’s job.

Check the diagram. See how the diaphragm is basically the floor of your ribcage? When it drops, your belly should expand. If it doesn't, you're misusing your anatomy.

Actionable Steps for Better Body Awareness

Stop treating your body like a collection of parts. Start treating it like a system.

- Identify Fiber Direction: Look at a high-quality diagram of body muscles and trace the lines of the muscles. If you’re stretching your hamstrings, realize there are three distinct muscles there, and they don't all run perfectly straight. Rotating your foot inward or outward during a stretch hits different parts.

- Address the "Antagonists": For every muscle that shrinks (contracts), there is one on the other side that must lengthen. If your chest is tight from slouching at a desk, your back muscles are stuck in a "long and weak" position. You don't need to stretch your back; you need to strengthen it and stretch your chest.

- Don't Ignore the Feet: There are 20 muscles in the human foot. Most diagrams skip them or lump them together. But your "foot core" is the foundation for everything else. If your foot muscles are weak, your knees and hips will pay the price.

- Use 3D Apps: Static 2D posters are okay, but 3D anatomy apps (like Complete Anatomy or Muscle & Motion) let you peel back layers. You can see how the rotator cuff sits deep inside the shoulder socket, protected by the deltoid.

Understanding your musculature isn't about passing a biology quiz. It’s about knowing how to move without pain. When you look at a diagram of body muscles, you're looking at the blueprint of your potential. Just remember that the map is not the territory. Your body has its own unique kinks, attachments, and imbalances that no generic drawing can ever fully capture.

Start by palpating—actually touching—the muscles you see on the screen. Feel the tendon of your bicep near the elbow. Feel the hardness of your quad when you lock your knee. Connect the visual image to the physical sensation. That is how you bridge the gap between "studying anatomy" and actually owning your body.