You’ve seen them in the back of old Bibles or hanging in a dusty hallway at your aunt’s place. A messy sprawl of names. Lines going everywhere. Most people think a diagram of a family tree is just a simple Sunday afternoon project, but honestly, once you start digging into census records from 1880, you realize it’s more like a forensic investigation. It's a map of how you got here. But it’s also a giant puzzle where half the pieces are missing or, worse, someone intentionally hid them a century ago.

Genealogy isn't just for retirees with too much time on their hands anymore. Since the explosion of DNA testing kits like AncestryDNA and 23andMe, millions of people are trying to visualize their "bloodline." But here is the thing: a diagram is only as good as the paper trail behind it. If you’ve ever tried to draw one out, you know the immediate frustration of hitting a "brick wall." That's the industry term for when a relative just... vanishes from the historical record.

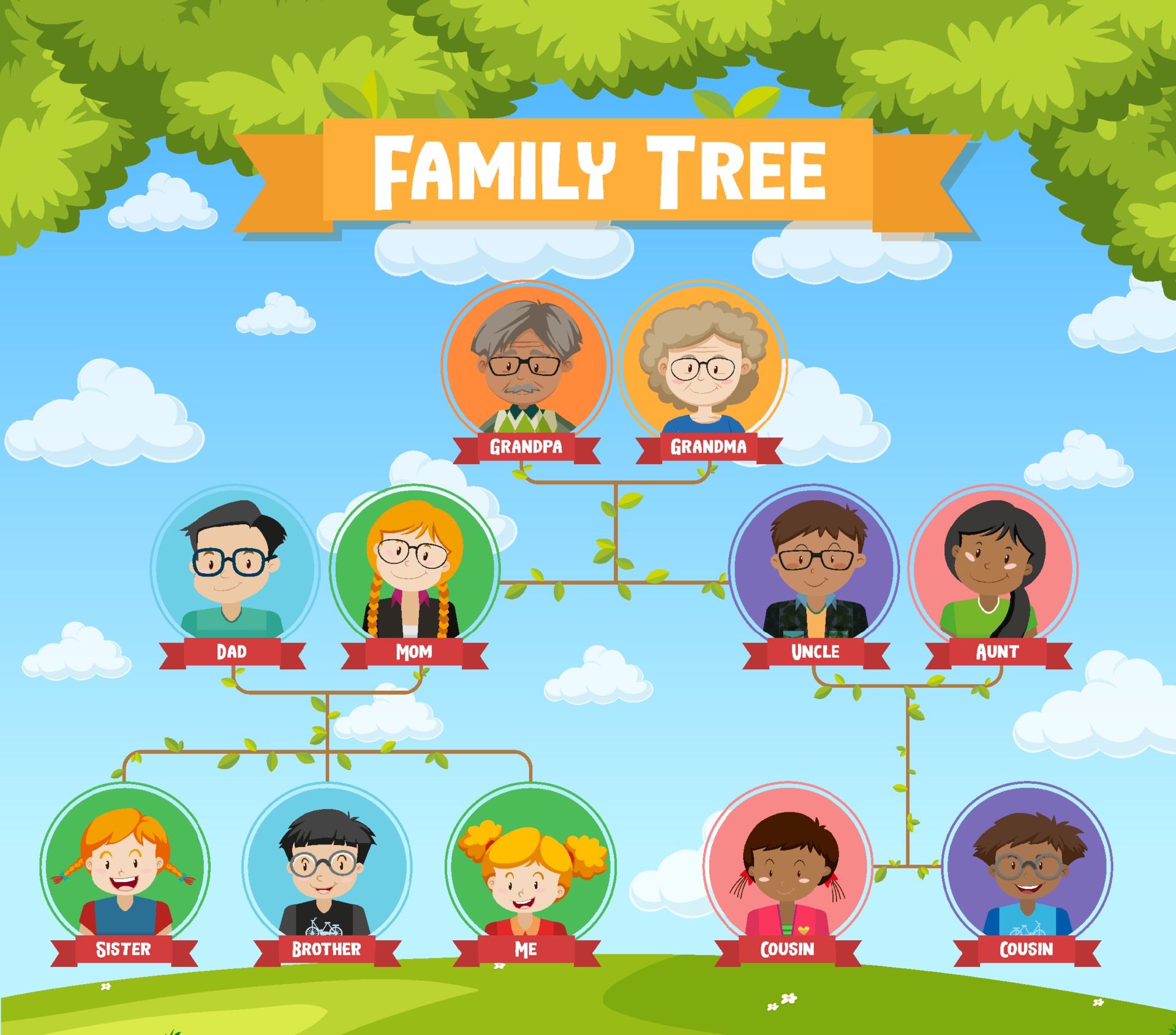

The basic anatomy of a family tree diagram

Basically, you start with yourself at the bottom or the center. You are the "progenitor" of this specific search. From there, you branch upward. Most beginners use a pedigree chart. This is the standard view. It shows your parents, their parents, and so on. It’s a clean, geometric expansion. 1, 2, 4, 8, 16. It doubles every generation. By the time you get back ten generations, you're looking at 1,024 ancestors.

Think about that for a second.

That is over a thousand people whose specific life choices, survival instincts, and random meetings led directly to you sitting here reading this. If one of them had stepped left instead of right during a thunderstorm in 1740, you wouldn't exist. That’s the weight of a diagram of a family tree. It’s not just names; it’s a statistical miracle.

But wait. There’s also the descendant chart. This is the opposite. You pick an old ancestor—say, a Great-Great-Grandfather who fought in the Civil War—and you map every single person who came from him. These diagrams get massive. They look like a web. If you’re doing this for a family reunion, you’re going to need a lot of poster board. Or, more realistically, a high-end software like Family Tree Maker or RootsMagic because doing this by hand is a recipe for a headache.

💡 You might also like: Apartment Decorations for Men: Why Your Place Still Looks Like a Dorm

Why vertical lines are a lie

Real life is messy. Standard diagrams use straight, clean lines to connect couples. But what about "informal" adoptions? What about the "cousin" who was actually a half-sibling? In the 19th century, record-keeping was... let’s say, flexible. You’ll often find that a diagram of a family tree needs to account for multiple marriages, step-children, and common-law situations that don't fit into a neat little box.

Professional genealogists, like those certified by the Board for Certification of Genealogists (BCG), often use "dashed lines" to indicate relationships that are suspected but not proven. It’s about intellectual honesty. If you don't have a birth certificate or a baptismal record, that line on your chart is just a guess. A "theory."

The DNA revolution changed the shape of the tree

Everything changed when we started spitting into tubes. Before DNA, a diagram of a family tree was based entirely on what people said was true. Now, it’s based on what your centimorgans (cMs) say is true. A centimorgan is just a unit of genetic measurement. If you share 3,400 cMs with someone, that’s your parent or child. No doubt.

But sometimes, the DNA doesn't match the paper.

This is what researchers call an "MPE"—a Non-Paternity Event or a Misattributed Parentage Experience. It happens way more than you’d think. You might have a perfectly inked diagram showing your Great-Grandfather was a certain man, but your DNA matches a completely different surname in the same county. Suddenly, your diagram is wrong. You have to redraw the whole branch. It’s jarring. It’s emotional. It’s why many people find genealogy to be a bit of a roller coaster.

📖 Related: AP Royal Oak White: Why This Often Overlooked Dial Is Actually The Smart Play

Common mistakes in your family diagram

People rush. That’s the biggest issue. You find a name that matches—"John Smith" born in 1850—and you click "add to tree." Stop.

- Same-Name Syndrome: There were probably five John Smiths in that county. If you attach the wrong one, every single person above him in your diagram of a family tree is a stranger to you. You're researching someone else’s family.

- The "Royal" Trap: Everyone wants to be related to Charlemagne or a Mayflower passenger. While mathematically, most people with European descent are related to Charlemagne, proving it line-by-line is nearly impossible for the average person. If your tree suddenly jumps from a farmer in Ohio to a Duke in England without five layers of proof, your diagram is likely fiction.

- Ignoring the Women: For centuries, records focused on men. Land deeds, tax rolls, military records—they all highlight the patriarch. A good diagram makes a concerted effort to find maiden names. Without the mother's line, you're missing 50% of the story.

Beyond the paper: Making it visual

If you want a diagram of a family tree that actually looks good on a wall, you have to move past the software-generated boxes. There are amazing artists on sites like Etsy who take your data and turn it into literal trees, with roots and branches. Or "fan charts."

A fan chart is a semi-circle. You are the center, and the generations radiate outward in colorful wedges. It’s the best way to see where your research is lacking. If one side of the fan is full of names and the other side is white space, you know exactly where you need to spend your next Saturday at the library.

Tools of the trade

You don't need a PhD, but you do need a system. Honestly, if you're just starting, use a free tool like FamilySearch. It’s a "collaborative" tree, meaning everyone works on one giant global diagram of a family tree. It’s great for finding photos others have uploaded, but it can be annoying when a random stranger changes your data.

For a private, "don't touch my stuff" approach, Ancestry.com is the king. Their "hints" (the little shaking leaves) are helpful but dangerous. They’re suggestions, not facts. You have to verify them.

👉 See also: Anime Pink Window -AI: Why We Are All Obsessing Over This Specific Aesthetic Right Now

Then there’s the "Genogram." This is a more clinical version of a family tree used by therapists and doctors. It doesn't just show who people were; it shows their relationships. Were they close? Did they have a rift? Did they struggle with heart disease or alcoholism? A genogram is a diagram of a family tree with a soul. It maps the trauma and the triumphs. It’s incredibly useful for health history. If you see a pattern of early heart attacks on the paternal side of your diagram, that’s actionable information for your own doctor.

The "Brick Wall" and how to break it

Eventually, you will hit 1800, 1750, or 1700, and the records will just... stop. Maybe the courthouse burned down (a common tragedy in the Southern US). Maybe your ancestors were illiterate and didn't leave diaries.

To keep your diagram of a family tree moving, you have to look at "FANs." That stands for Friends, Associates, and Neighbors. People traveled in groups. If your ancestor disappears, look at who lived next door to them in the previous census. Usually, those families moved together. Find the neighbor's records, and you’ll often find your ancestor mentioned in a will or a land boundary dispute.

It’s about being a detective. It’s about looking at a name on a page and realizing that was a living, breathing person who felt the cold, loved their kids, and worried about the harvest. When you look at your diagram, try to see the people, not just the ink.

Actionable steps for your tree

Don't try to do it all at once. You’ll burn out.

- Start with the living. Interview your oldest relatives today. Not next month. Today. Record the audio. Ask about the "black sheep." Ask about the stories they heard as kids. These clues are more valuable than any database.

- Verify one link at a time. Don't add a generation until you have at least two pieces of evidence linking the child to the parent. A census record and a birth certificate. A death record and a will.

- Use a standard naming convention. Write dates as "Day Month Year" (e.g., 12 May 1910) to avoid confusion between US and European formats. Use maiden names for women.

- Organize your digital files. If you download a death certificate, name the file something useful like "SMITH_John_Death_1892.pdf" instead of "download_123.pdf." Your future self will thank you.

- Look for the "unwritten" clues. Check the back of old photos for handwriting. Look at the names of sponsors on baptismal records—they are almost always close relatives who belong on your diagram of a family tree.

Building this isn't about being fancy or finding royal blood. It’s about knowing your place in the timeline. It’s a way to make sure that a hundred years from now, your name isn't the one people are struggling to find. Get it on paper. Make it permanent.