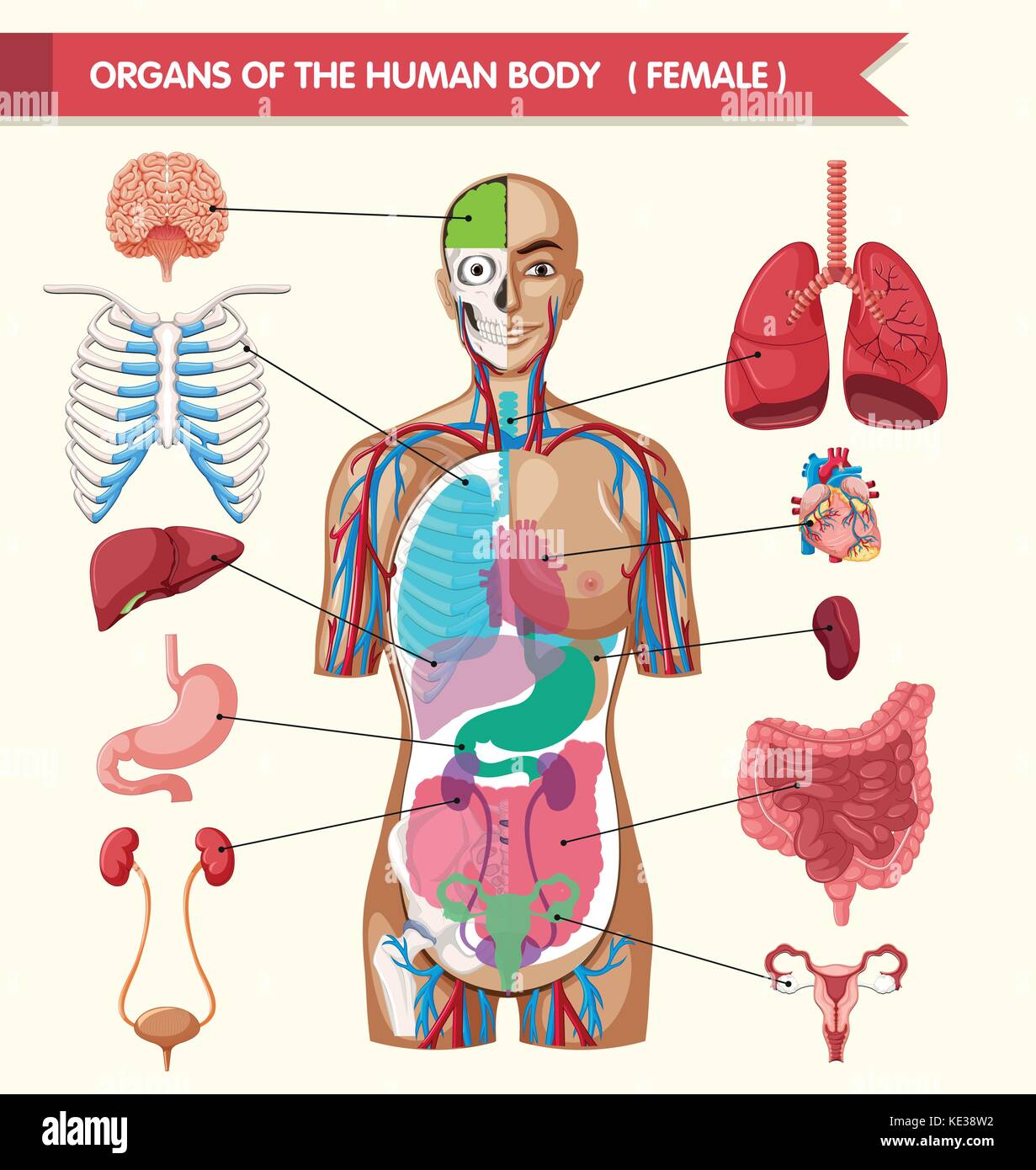

You’ve seen them since third grade. Those neon-colored posters in the nurse's office or the glossy pages of a biology textbook showing a diagram inside human body cavities. They look clean. Everything is color-coded—blue veins, red arteries, bright yellow nerves. It’s all very tidy.

But honestly? Real anatomy is a mess.

If you actually looked inside a human being, you wouldn't find those crisp lines. You’d find a wet, pulsating, crowded space where organs are squished together, held in place by a cling-wrap-like substance called fascia. Most people think their stomach is behind their belly button because of a simplified diagram inside human body layouts. It’s actually much higher, tucked under your ribs on the left. We grow up with these mental maps that are basically the "London Underground" version of our guts: useful for navigation, but geographically lying to us.

The Evolution of Mapping the Internal Self

We didn't always have high-resolution 3D renders. Early anatomical drawings were kind of a guess. In the 2nd century, Galen was the authority, but he mostly dissected pigs and monkeys. He just assumed humans were the same. It took over a thousand years for Andreas Vesalius to come along in the 1500s and say, "Hey, maybe we should actually look at a person."

His work, De humani corporis fabrica, changed everything. It wasn't just a diagram inside human body structures; it was art. He showed muscles peeling off the bone like layers of an onion. Even then, it was stylized. Today, we use Netter’s Atlas of Human Anatomy. Frank Netter wasn't just a doctor; he was an artist. His illustrations are the gold standard for med students, but even he had to make choices about what to leave out to make the "map" readable.

Why Color Coding is a Lie (But a Useful One)

In a standard diagram inside human body systems, the colors are there for your brain, not for accuracy.

✨ Don't miss: The Spanish Flu Epidemic 1918: What Most People Get Wrong About the Deadliest Year in History

- Arteries are red because they carry oxygenated blood.

- Veins are blue, which is weird because in real life they are more of a dark maroon or purple.

- Nerves are yellow, though they actually look like white, frayed pieces of string.

If a surgeon saw a bright yellow nerve glowing in your arm, they’d probably be terrified. This abstraction is necessary because, without it, everything just looks like various shades of pinkish-beige.

The Crowded Reality of the Torso

Let’s talk about the "void." There isn't one.

When you look at a diagram inside human body cross-sections, there seems to be air or space between the liver and the stomach. There isn't. Everything is packed in with zero tolerance. If you’ve ever tried to pack a suitcase that’s too full and had to sit on it to zip it up, that’s your abdomen.

Your small intestine is about 20 feet long. Think about that. Twenty feet of tubing shoved into a space smaller than a shoebox. It’s constantly moving, a process called peristalsis. A static diagram can’t show that rhythmic, snake-like churning. It makes the body look like a machine with fixed pipes, but it’s more like a bag of very active eels.

The Fascia: The Part Diagrams Forget

One huge flaw in almost every diagram inside human body collection is the omission of fascia. Fascia is the connective tissue that wraps around every muscle, organ, and nerve.

For a long time, medical students were taught to just cut it away to get to the "important" stuff. But recently, researchers like those involved in the International Fascia Research Congress have realized it’s a massive communication network. It’s not just "packing peanuts" for your organs. It’s a sensory organ in its own right. When you see a diagram where the liver is just floating in mid-air, you’re seeing a lie. It’s anchored by a complex web of translucent, incredibly strong webbing.

Mental Maps and Diagnostic Errors

Why does this matter? Because your mental diagram inside human body regions affects how you describe pain.

I’ve talked to doctors who say patients often point to their hip bone when they say their "kidneys hurt." Your kidneys are actually much higher up, nestled against the muscles of your back, protected by your lower ribs. If you rely on a simplified map, you might ignore a serious symptom or obsess over a benign one.

👉 See also: How to Make My Stomach Stop Hurting: What Actually Works and Why

Then there's the appendix. We always see it in the lower right. But some people are born with "situs inversus," where their organs are mirrored. Their heart is on the right, liver on the left. A standard diagram inside human body would be completely backwards for them. Even in "normal" people, the appendix can be "retrocecal," meaning it’s tucked behind the large intestine instead of hanging off the bottom.

Technology is Changing the Map

We’re moving away from the 2D poster. We have the "Visible Human Project," where a cadaver was literally sliced into thousands of thin layers and digitized. Now, surgeons use AR (Augmented Reality) to overlay a digital diagram inside human body directly onto a patient's skin before the first incision.

It’s like GPS for the gallbladder.

But even with this tech, the "map is not the territory." Every body is a unique mess of scars, fat deposits, and slightly-off-center plumbing.

How to Use Anatomy Diagrams Without Getting Confused

If you’re looking at a diagram inside human body for health reasons, keep a few things in mind. First, check the "view." Is it anterior (front), posterior (back), or sagittal (side-slice)? Most people get turned around looking at CT scans because they don't realize they are looking at their body from the feet up.

Second, remember that size is relative. A diagram inside human body often blows up the size of the endocrine glands—like the pituitary or the adrenals—so you can actually see them. In reality, your adrenal glands are tiny little hats sitting on your kidneys, easily missed if you aren't looking for them.

Real Actionable Insights for the Curious

Don't just stare at a static image. If you want to understand your own "internal diagram," try these steps:

💡 You might also like: Finding Your Next Pair: Why Visionworks Silver Spring Square Is Actually Worth the Trip

- Palpate correctly: Find your lower rib cage. Your liver is mostly tucked under the right side. Take a deep breath; your diaphragm pushes it down, and you can sometimes feel the edge of it.

- Use 3D Apps: Download something like Complete Anatomy or BioDigital. Unlike a flat diagram inside human body, these let you rotate and peel away layers. It's much more intuitive.

- Trace the path: If you’re tracking digestion, don't just look at the stomach. Realize the path goes from the esophagus, through the cardiac sphincter, into the stomach, through the pyloric sphincter, into the duodenum, and so on.

- Acknowledge the Fascia: When you stretch, realize you aren't just stretching a "muscle" like a rubber band in a diagram. You are stretching a continuous suit of connective tissue that links your neck to your toes.

The human body is an incredible, crowded, wet, and chaotic masterpiece. A diagram inside human body is a great starting point, but it's just a sketch of a much more complex reality. Stop thinking of yourself as a collection of separate parts and start seeing the interconnected, squished-together truth.

To really understand your health, you have to look past the clean lines of the textbook and embrace the beautiful, functional clutter of the actual human form. Turn the page, rotate the model, and remember that you are not a poster on a wall.