You probably remember it from seventh grade. That neon-green poster on the classroom wall showing a "typical" cell that looked vaguely like a fried egg or a lumpy brick. Most of us just memorized the parts to pass a quiz and then deleted that data from our brains forever. But honestly, if you look at a diagram for plant and animal cell structures today, you’ll realize it’s not just biology homework. It is the literal blueprint of how life stays alive.

We are made of trillions of animal cells. The salad you ate for lunch? That was a collection of plant cells. Understanding the tiny, mechanical differences between them explains why humans can’t photosynthesize (bummer) and why trees don't need a skeleton to stand up straight. It’s all down to the architecture.

The Basic Anatomy: What’s Inside the Bag?

Think of a cell like a tiny, high-tech factory. Both types have a "management office" (the nucleus) and a "shipping department" (the Golgi apparatus).

Every animal cell is wrapped in a flexible, oily skin called the cell membrane. It’s soft. It’s squishy. This is why you are soft and squishy. Because animal cells lack a rigid outer wall, they can bunch up into complex shapes like neurons or muscle fibers. Plant cells, on the other hand, are like tiny cardboard boxes stacked on top of each other. They have a cell wall made of cellulose—the same stuff in your cotton t-shirts—which gives them that signature "crunch" when you bite into a carrot.

The Powerhouse Debate

Everyone loves to shout "the mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell!" at parties to sound smart. And yeah, it’s true. Both plant and animal cells have mitochondria. They take glucose and turn it into ATP, which is basically cellular gasoline.

But plants have a secondary power source that we don’t. Enter the chloroplast.

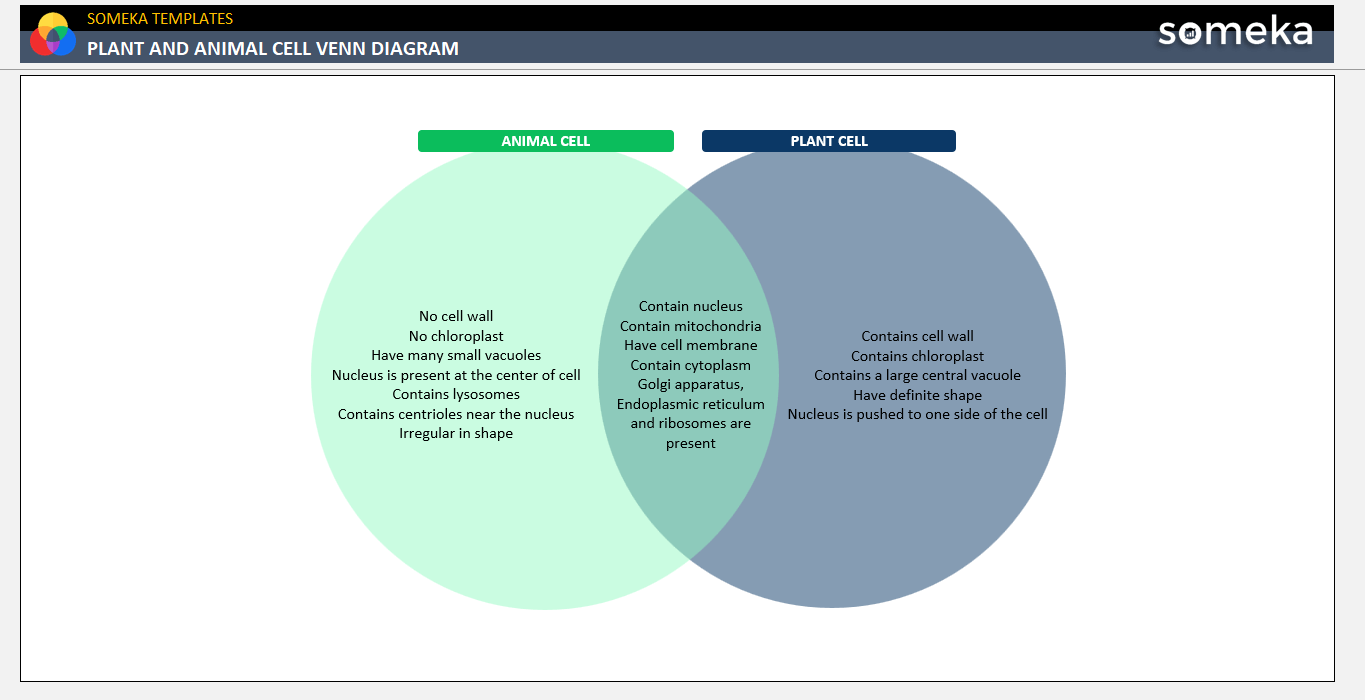

If you look at a diagram for plant and animal cell side-by-side, the chloroplast is usually the green, bean-looking thing in the plant section. These little guys contain chlorophyll, which captures sunlight. It’s essentially a solar panel. While we have to go find a sandwich to get energy, plants just stand in the sun and make their own. It’s an incredibly efficient system that keeps the entire planet’s food chain from collapsing.

The Weird Stuff: Vacuoles and Trash Cans

One of the biggest visual differences in any diagram for plant and animal cell is the "large central vacuole."

In a plant, this is a massive, water-filled balloon that takes up almost 90% of the interior space. Why? Turgor pressure. When the vacuole is full, it pushes against the cell wall, making the plant stand up straight. When you forget to water your peace lily and it wilts, it’s because those vacuoles have deflated.

Animal cells have vacuoles too, but they’re tiny and temporary. We use them more like little storage bins or trash cans.

Speaking of trash cans, let’s talk about lysosomes. For a long time, textbooks said only animal cells had them. We thought plants just used their big central vacuole to break down waste. Recent research, including studies published in Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, suggests that some plants might have lysosome-like structures, but for the most part, the lysosome is the "stomach" of the animal cell. It’s full of enzymes that melt down cellular debris. Without them, our cells would basically turn into tiny hoarding houses full of broken proteins.

Why the Shape Isn't Just for Show

If you’ve ever looked at a slide under a microscope, you’ll notice animal cells are messy. They’re irregular. They’re blobs.

Plant cells are almost always rectangular or cubic.

This geometric difference is why wood is hard and your bicep is soft. The cellulose in plant cell walls is a structural masterpiece. In fact, Robert Hooke, the guy who actually coined the term "cell" in 1665, did so because he was looking at cork (plant cells) under a primitive microscope and thought they looked like the small rooms—or cella—where monks lived.

Cytoplasm: The Jelly that Holds it All Together

In any diagram for plant and animal cell, there’s a lot of "empty" space. Except it’s not empty. It’s filled with cytoplasm. This isn't just water; it's a thick, protein-rich gel.

Imagine trying to swim in a pool filled with fruit-flavored Jell-O. That’s what it’s like for an organelle. This jelly provides a medium for chemicals to move around. In animal cells, the cytoskeleton—a network of tiny protein tubes—acts like a scaffolding to keep the cell from collapsing. In plants, the cell wall does most of the heavy lifting, but the cytoskeleton still helps move things around internally.

The Genetic Command Center

The nucleus is the VIP lounge. Inside, you’ll find the DNA.

Whether it’s an oak tree or a golden retriever, the nucleus operates similarly. It’s surrounded by a nuclear envelope that has tiny pores. These pores are like bouncers; they only let specific molecules in and out. This is where the instructions for making "you" are kept.

When you see a diagram for plant and animal cell, notice the rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER) hugging the nucleus. It’s "rough" because it’s studded with ribosomes. This is where proteins are built. It’s the literal factory floor of life.

Real-World Nuance: It’s Not Always Black and White

Biology is messy. While we use these diagrams to teach the basics, there are always exceptions.

For instance, did you know some animal cells have cilia (tiny hairs) to help them move, while most plant cells don't? But then you have moss sperm—yeah, that’s a thing—which actually has flagella to swim through water to reach an egg.

Also, the "typical" cell diagram usually ignores specialized cells. A red blood cell in your body doesn't even have a nucleus! It kicks it out to make more room for oxygen. A xylem cell in a tree is actually dead at maturity; it’s just a hollow tube used for plumbing.

When we look at a diagram for plant and animal cell, we’re looking at a generalized "average." It’s like looking at a drawing of a "typical house" to understand how a skyscraper or a yurt works. It gives you the foundation, but the reality is way more diverse.

Practical Insights for Your Everyday Life

Understanding this microscopic world actually changes how you interact with the planet.

- Nutrition: When you eat "fiber," you are literally eating the cell walls of plants. Since humans lack the enzyme (cellulase) to break down that tough cellulose, it passes through us, keeping our digestive tracts moving.

- Medicine: Many antibiotics work by attacking the cell walls of bacteria. Since animal cells don't have cell walls, the medicine kills the bacteria without hurting you.

- Agriculture: Understanding how the large central vacuole handles salt can help scientists develop crops that can grow in poor soil conditions.

Next Steps for Mastering Cell Biology

If you want to actually use this knowledge or help a student nail their next exam, don't just stare at a static image.

First, try to draw a diagram for plant and animal cell from memory. It’s the "testing effect"—a proven psychological phenomenon where the act of retrieving information makes it stick way better than just reading it.

Second, if you have a child or just a curious Saturday afternoon, build a 3D model. Use Jell-O for the cytoplasm and different candies for the organelles. Use a sturdy plastic container for the plant cell (the cell wall) and a flexible Ziploc bag for the animal cell (the cell membrane).

Finally, look up high-resolution "fluorescence microscopy" images. Real cells aren't neon green and purple; they are complex, glowing, moving machines. Seeing the actual movement of a mitochondria traveling along a cytoskeletal "highway" will make that boring textbook diagram feel a lot more like the miracle it actually is.

Explore the world of microbiology by using a home microscope kit to look at an onion skin versus a cheek swap. You will see the "bricks" of the plant and the "blobs" of the animal right before your eyes.