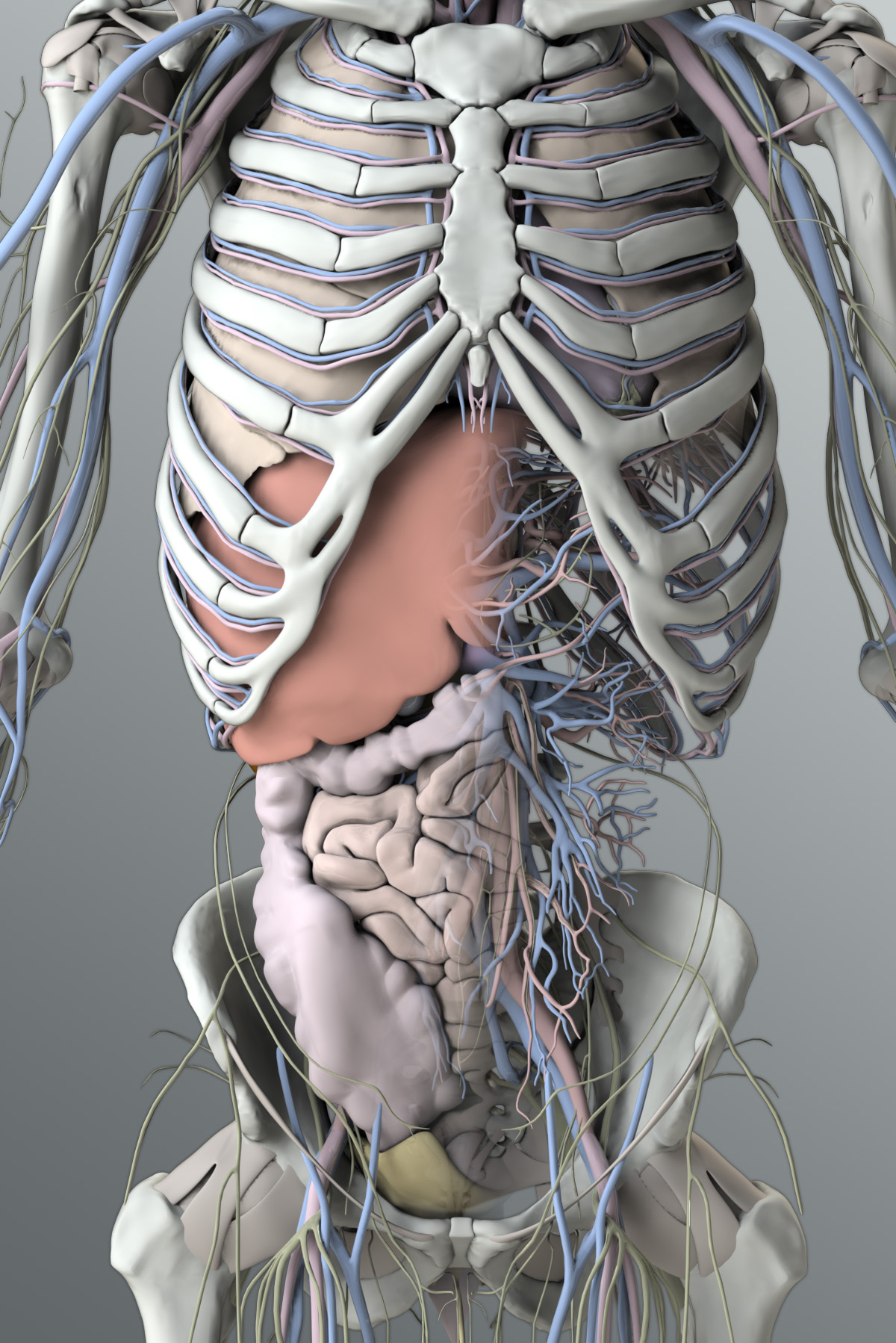

Ever looked at a high-res picture of the human anatomy with organs and felt like you were staring at a cluttered subway map? It’s messy. Honestly, it’s a miracle anything works at all. We like to think of our insides as these neatly tucked-away packages, but the reality is much more cramped. Everything is touching everything else. Your liver is basically hugging your diaphragm, and your small intestine is coiled up like a panicked garden hose in a space way smaller than you’d think.

Most people see these diagrams in a doctor's office or a textbook and assume they're looking at a static "map." But that's not how it works in a living, breathing person. Your organs shift. They move when you inhale. They relocate slightly during pregnancy. Understanding the geography of your own torso isn't just for medical students; it’s about knowing why a pain in your "stomach" might actually be your gallbladder or why your "back pain" is actually a kidney stone making a slow, miserable exit.

The Crowded Reality of Your Core

If you peel back the skin and the abdominal wall, you don't find empty space. It’s tight in there. The "classic" picture of the human anatomy with organs often hides the fascia—that thin, cling-wrap-like tissue that keeps everything from just sloshing around.

Take the liver. It's the heavy hitter. Literally. It weighs about three pounds and sits mostly on your right side, tucked under the rib cage. It’s so big that it actually forces the right kidney to sit a bit lower than the left one. Most people don't know that. They think kidneys are a perfectly symmetrical pair, like earrings. Nope. Biology is asymmetrical and weirdly pragmatic.

Then there’s the stomach. It’s not down by your belly button. It’s actually quite high up, tucked under the left side of your ribs. When people point to their lower abdomen and say "my stomach hurts," they are usually pointing at their large intestine or their bladder. It’s a common mix-up.

Why the "Standard" Map is Kinda Lying to You

The diagrams we see are usually based on a "textbook" male or female of average height and weight. But real human bodies vary wildly. Some people have "situs inversus," where their organs are literally mirrored. Their heart is on the right, and their liver is on the left. It’s rare—about 1 in 10,000 people—but it proves that the picture of the human anatomy with organs we all study is just a general suggestion, not a universal law.

📖 Related: Products With Red 40: What Most People Get Wrong

The Plumbing: It’s Longer Than You Think

Let’s talk about the intestines. This is where the "map" gets really complicated. If you were to unspool the small intestine, you’re looking at about 20 feet of tubing. Twenty. Feet. It’s packed into the central abdominal cavity through a series of complex folds.

- The Duodenum is the first part, right after the stomach. It’s short but vital for chemical breakdown.

- The Jejunum and Ileum do the heavy lifting of nutrient absorption.

- The Large Intestine (colon) wraps around the small intestine like a frame.

It’s not just about length, though. It’s about the blood supply. The mesenteric arteries feed this whole system, and if you saw a real picture of this vascular network, it would look like a dense, terrifying bird’s nest.

The Lungs and Heart: The High-Pressure Zone

Up in the chest (the thoracic cavity), things are even more compressed. Your heart isn't on the "left side" of your chest; it's mostly in the middle, just tilted to the left. This tilt means your left lung is actually smaller than your right lung. It has to make room for the heart’s "cardiac notch."

The right lung has three lobes, but the left only has two. It’s a compromise. Space is the most valuable real estate in the human body, and the heart is the tenant that gets whatever it wants.

Misconceptions That Actually Matter

People often get the "where" and "what" wrong when looking at a picture of the human anatomy with organs. For instance, the appendix. Everyone knows it's on the lower right, right? Usually. But it can actually be tucked behind the large intestine (retrocecal), which makes diagnosing appendicitis a total nightmare for surgeons.

👉 See also: Why Sometimes You Just Need a Hug: The Real Science of Physical Touch

And the pancreas? Most people couldn't point to it on a map. It’s tucked deep behind the stomach, crossing the midline of the body. Because it’s so deep, issues with the pancreas often feel like "deep" back pain, which leads to people ignoring it for far too long.

Then there's the spleen. It sits on the far left, protected by the lower ribs. It’s soft, like a sponge filled with blood. In a car accident, this is one of the most commonly injured organs because it’s so fragile and tucked right against the rib cage, which can fracture and pierce it.

Digital vs. Physical: How We See Inside Today

We’ve moved past the hand-drawn sketches of Andreas Vesalius. Today, we have 3D renders and MRI reconstructions. But even these high-tech images are just snapshots. A real picture of the human anatomy with organs in a living person would show constant movement. Pulsing. Peristalsis (the wave-like contraction of the gut). The diaphragm sliding up and down.

When you look at a static image, you’re seeing a "dead" version of a "living" system. Experts like Dr. Gunther von Hagens, famous for the Body Worlds exhibits, showed us what the body looks like when preserved, but even those "plastinated" specimens are rigid. In you, right now, your organs are slippery, wet, and constantly shifting.

The Bio-Mechanical Connection

The way these organs are stacked affects your posture and vice versa. If you’re constantly slouching, you’re literally compressing your digestive organs and your lungs. This isn't just some "wellness" talk; it’s physics. Your diaphragm needs space to drop down so your lungs can expand. If your "internal map" is squished by bad posture, your organs can't function at 100%.

✨ Don't miss: Can I overdose on vitamin d? The reality of supplement toxicity

Practical Steps for "Anatomy Literacy"

You don't need a medical degree, but you should know your own layout. It saves time and anxiety.

- Locate your landmarks. Find your lower rib cage. That’s the "roof" for your liver and stomach.

- Understand "Referred Pain." Know that heart issues can feel like jaw pain, and gallbladder issues can feel like right shoulder pain. The nerves in our internal "map" get crossed easily.

- Trace the flow. Visualize your digestive tract. When you eat, it goes down the esophagus (behind the windpipe), into the stomach (top left), through the small intestine (middle), and out the large intestine (the "frame").

- Check your breathing. Put your hand on your belly. When you breathe in, your belly should move out. That’s your diaphragm pushing your organs down to make room for air. If that's not happening, you're "chest breathing," which is way less efficient.

The Reality of the "Internal Map"

The human body is an incredible feat of spatial engineering. We have miles of vessels, dozens of organs, and hundreds of bones all fitting into a skin-tight suit. Next time you see a picture of the human anatomy with organs, don't just look at it as a diagram. Look at it as a high-stakes puzzle where every piece is vital, and space is the ultimate luxury.

Knowing where things are—and more importantly, where they actually sit versus where we think they sit—is the first step in better health communication. When you can tell a doctor, "I have a sharp pain in my right upper quadrant, right under the ribs," you're speaking their language. You're using the map correctly. And in a medical emergency, that clarity is worth more than any textbook diagram.

To get a better handle on this, start by palpating your own rib cage. Feel where the bone ends and the soft tissue begins. That's the border of your thoracic and abdominal worlds. Notice how your breath changes that boundary. That's your anatomy in motion. It's not a static picture; it's a living, shifting reality.