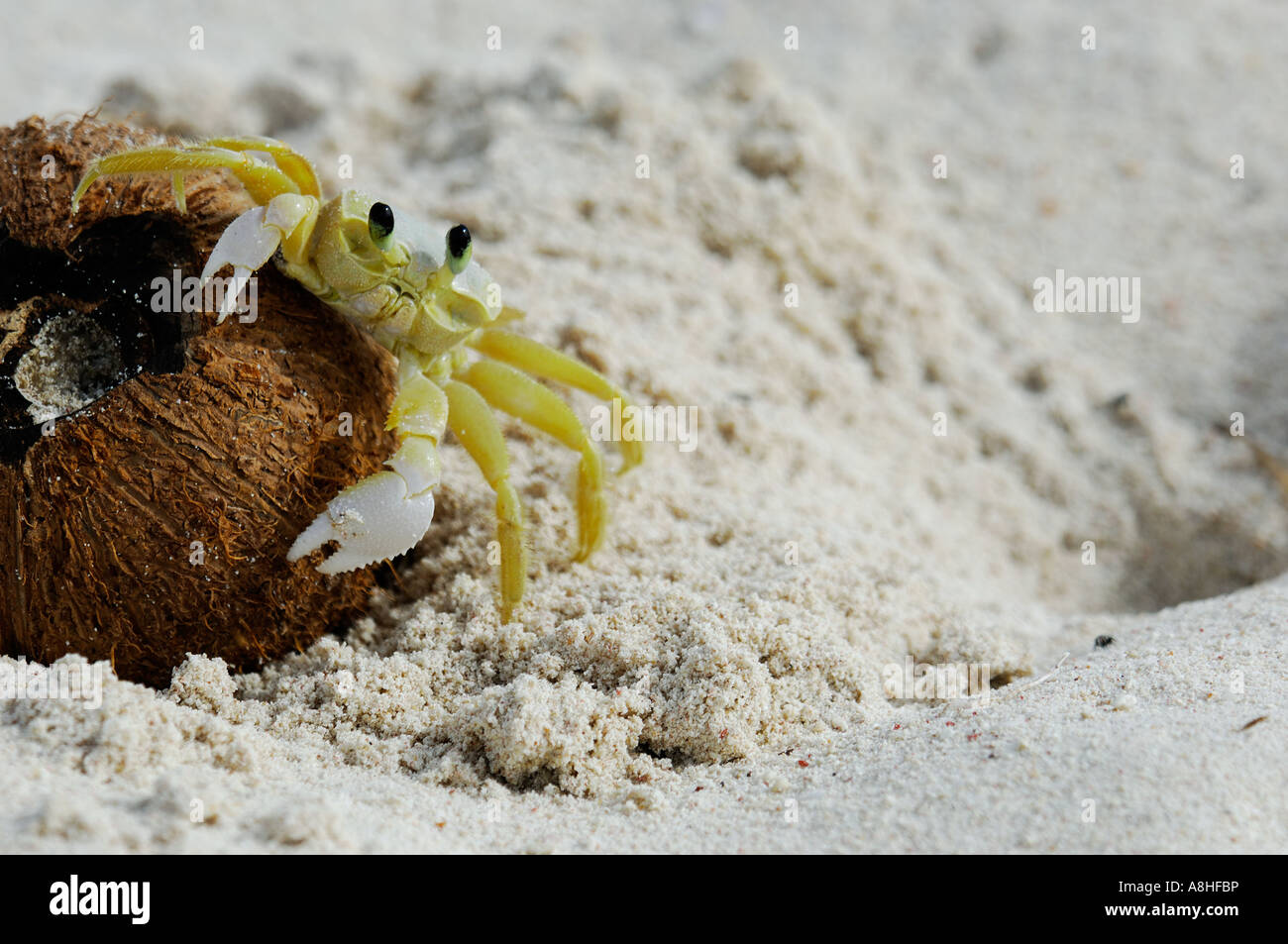

They are massive. Honestly, if you saw a three-foot-wide crab crawling up a tree in your backyard, you’d probably lock the door and call someone. But for the Birgus latro, better known as the coconut crab, that's just a Tuesday. These giants are the largest land-living arthropods on the planet, and their relationship with their namesake fruit is way more complex than just a hungry animal finding a snack. It’s a multi-day engineering project.

Most people think a coconut crab eating a coconut is a quick affair. It’s not. It’s a test of endurance and sheer physical power that no other crustacean can match.

💡 You might also like: Why the Loewe x Suna Fujita Collaboration is Actually Worth the Hype

The Ridiculous Strength Required to Crack a Nut

Imagine trying to open a coconut with your bare hands. You can't. You’d need a machete or a drill. But these crabs? They have evolved specialized pincers that can exert a force of up to 3,300 Newtons. To put that into perspective, that is roughly ten times the grip strength of an average human male and actually exceeds the bite force of most land predators, including leopards.

Researchers like Shin-ichiro Oka have spent years measuring these forces in the field. They found that the pinching power of a large coconut crab is comparable to the bite of a lion. This isn't just for show; they need every bit of that pressure to get through the husk.

The process is slow. Methodical. A crab will first strip away the fibrous outer husk, fiber by fiber. This can take hours, or even days depending on the size of the nut and the persistence of the crab. They use their smaller walking legs to probe the "eyes" of the coconut, searching for the weakest point. Once they find a soft spot, they begin the heavy lifting. They don't just "crack" it—they systematically dismantle it.

Why Do They Even Bother?

Coconuts are hard work. If you're a crab, why not just eat some rotting fruit or a dead bird? Well, they do that too. Coconut crabs are famous generalist scavengers. They've been known to eat kittens, chickens, and even—as some gruesome theories suggest—the remains of Amelia Earhart (though that remains an unproven legend).

But the coconut is a high-fat, high-energy prize. In the tropical Indo-Pacific islands where they live, resources can be scarce. A single coconut provides a massive caloric payout. It’s the difference between surviving and thriving. Interestingly, despite their name, they don't need coconuts to survive. Crabs on islands without coconut palms grow just fine, but they usually don't reach the monstrous sizes of their nut-cracking cousins.

The Myth of the Tree-Climbing Thief

You might have heard that these crabs climb trees just to drop coconuts and break them. That is mostly a myth. While they are incredible climbers—reaching heights of over 30 feet with ease—they don't intentionally "drop" the fruit to crack it. Gravity isn't their primary tool; their claws are.

When you see a coconut crab eating a coconut high up in a palm, it’s usually because they found a nut that was already partially damaged or they are simply hiding their prize from competitors. These crabs are notoriously "crabby." They will fight each other over a single nut, and the loser often ends up losing a limb in the process.

They have a specialized sense of smell, too. Their antennae work more like an insect’s than a typical crab’s, allowing them to detect the scent of a ripening nut or a decaying carcass from a significant distance.

A Biological Oddity: Why They Drown

It’s weird to think about a crab that can’t swim. But if you toss a coconut crab into the ocean, it will drown. Evolution took a strange turn with these guys. While they start their lives in the sea as microscopic larvae, once they transition to land, they develop "branchiostegal lungs."

These are essentially a halfway point between gills and lungs. They need to keep these organs moist to breathe, which is why you’ll often find them lurking in damp crevices or coming out at night when the humidity is higher. They are the ultimate land-dwellers, fully divorced from the ocean except for the brief moment the females return to the shoreline to release their eggs.

Conservation and the Reality of the "Giant"

The sight of a coconut crab eating a coconut is becoming rarer. In many parts of their range, like Guam and parts of the Cook Islands, they are considered a delicacy. Because they grow so slowly—taking up to 50 years to reach their full size—they are incredibly vulnerable to overharvesting.

🔗 Read more: Why your tree of life tattoo means way more than you think

They are also remarkably curious and bold. They aren't afraid of humans. This "fearlessness" makes them easy targets for hunters. In places like the Christmas Island (the Australian territory, not the one in Kiribati), they are protected, and you can see them wandering around like prehistoric tanks. But elsewhere, habitat loss and invasive species are thinning their numbers.

The complexity of their behavior is still being studied. We know they "cache" food. We know they can remember where they found a meal. We even know they are capable of complex problem-solving when it comes to navigating obstacles. They aren't just "bugs"; they are intelligent, long-lived animals with a very specific niche in their ecosystem.

How to Observe Them Responsibly

If you ever find yourself on a tropical island in the Indian or Pacific Ocean and want to see this spectacle, keep a few things in mind:

- Look, don't touch. Those 3,300 Newtons of force can easily snap a finger.

- Flashlights are your friend. They are primarily nocturnal to avoid desiccation.

- Check the local laws. In many regions, it is strictly illegal to disturb or capture them.

- Watch the trees. They blend in remarkably well with the bark of a coconut palm.

Seeing a coconut crab eating a coconut is a reminder of how specialized evolution can get. It’s an animal that has literally adapted its entire body to crack one of the hardest natural shells in existence. It’s not just a meal; it’s a feat of biological engineering.

If you’re interested in supporting their conservation, look into organizations like the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which monitors their population status. Supporting sustainable tourism in places like the Seychelles or the British Indian Ocean Territory also helps ensure that the local economies value these giants more as a tourist attraction than as a menu item.

Next time you struggle to open a jar of pickles, just remember there’s a crab out there that could crush that jar into powder without breaking a sweat. It puts things in perspective. Just keep your distance and admire the grip.

Actionable Next Steps

- Verify Local Regulations: If traveling to the Indo-Pacific, check the IUCN Red List or local wildlife agency websites to see the protection status of coconut crabs in that specific territory.

- Support Habitat Preservation: Donate to or follow organizations like the Island Conservation group, which works to remove invasive species (like rats) that compete with or prey on young coconut crabs.

- Educational Outreach: Share factual information about their growth rates. Many people don't realize that a large crab might be 40+ years old, making their removal from the wild a significant blow to the local population.