It is loud. It is bright. It is honestly quite sickening. When Stanley Kubrick unleashed A Clockwork Orange film in 1971, he didn't just make a movie; he set off a cultural bomb that is still ticking. You’ve probably seen the poster. The one with Malcolm McDowell’s eye pinned open by a cold, metallic speculum. It’s an image that has become shorthand for cinematic rebellion, but the actual experience of watching the film is much more complicated than a cool t-shirt design.

People walked out. They really did. In the UK, the backlash was so visceral—including reports of "copycat" crimes—that Kubrick himself eventually pulled the film from distribution there. It wasn’t available legally in Britain for decades. That kind of aura doesn't just happen. It comes from a director who was obsessed with the thin, fragile line between civilization and the lizard brain.

The Ultra-Violence That Broke the Rules

We have to talk about the "ultra-violence." That's the term Alex DeLarge uses, and it’s become part of the lexicon. But Kubrick doesn't film it like a standard action movie. He uses Gene Kelly’s "Singin' in the Rain."

Why? Because it’s terrifying.

By layering a joyful, iconic American showtune over a brutal assault, Kubrick forces the audience into a state of cognitive dissonance. You want to tap your foot, but you want to vomit. It’s a masterful, if cruel, manipulation of the viewer. Most directors want you to identify with the hero. Kubrick, however, makes his protagonist a rapist and a murderer, then asks you to care when the state starts messing with his brain. It’s a trap. A brilliant, philosophical trap.

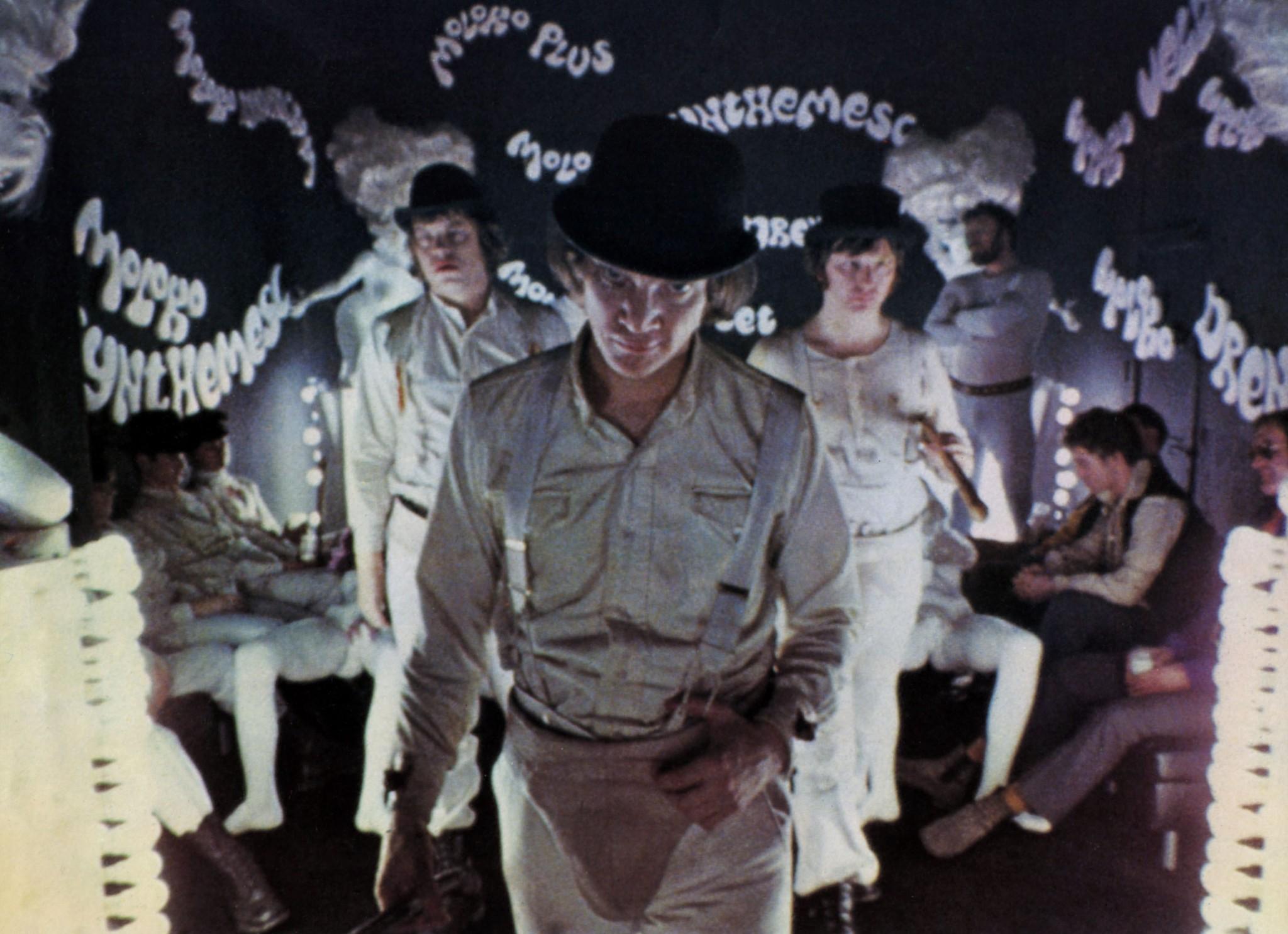

The visual language here is pure pop-art nightmare. Working with production designer John Barry, Kubrick created a world that feels like a futuristic 1970s. The Korova Milkbar, with its fiberglass nude furniture and "moloko plus," wasn't just a set. It was a statement on the objectification of the human form. Everything in the world of A Clockwork Orange film is transactional or predatory. There is no middle ground.

The Ludovico Technique and the Death of Free Will

The heart of the story—and the part that usually sparks the most late-night dorm room debates—is the Ludovico Technique.

👉 See also: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

Basically, the government decides that instead of just locking Alex up, they’ll "cure" him. They strap him into a chair, keep his eyes open, and force him to watch horrific imagery while drugged so that he becomes physically ill at the mere thought of violence.

Is a man still a man if he can no longer choose to be bad?

That’s the question Anthony Burgess asked in the original 1962 novella, and Kubrick leans into it with clinical precision. The prison chaplain is the only one who seems to get it. He argues that when a man cannot choose, he ceases to be a human being and becomes a "clockwork orange"—something organic and living on the outside, but mechanical and programmed on the inside.

The Missing Final Chapter

If you’ve only seen the movie, you’re missing the ending. Well, the original ending.

Anthony Burgess wrote 21 chapters. Kubrick based his screenplay on the American edition of the book, which only had 20. In that version, the story ends on a cynical, dark note: Alex is "cured" of his cure, and he’s back to his old self. "I was cured all right," he says, with that predatory glint in his eye.

But the 21st chapter? It’s completely different.

✨ Don't miss: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

In the final chapter, Alex simply gets older. He gets bored. He starts thinking about having a son and settling down. It’s a "maturation" ending. Kubrick hated it. He thought it was a cop-out, a weak attempt at redemption that didn't fit the character. Most film scholars agree that Kubrick's bleaker ending is what gave the film its staying power. It doesn't give you the "out" of a happy ending. It leaves you sitting in the dark, feeling the weight of Alex's return to power.

Sound and Fury: The Carlos Connection

The music isn't just background. It's a character. Wendy Carlos, using early Moog synthesizers, reimagined Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in a way that sounds both ancient and alien.

Alex’s obsession with "Ludwig van" is his only redeeming quality, yet it’s also his undoing. When the government conditions him, they inadvertently make him sick when he hears his favorite music. This is a specific kind of tragedy. The state doesn't just take away his ability to hurt people; it takes away his ability to experience beauty. It’s a nuance that often gets lost when people talk about the film’s "cool" aesthetic.

Why It Flooded the Cultural Zeitgeist

Think about the costumes. The white jumpsuits, the codpieces, the bowlers, the single eyelash. It’s high-fashion fascism.

Milena Canonero, the costume designer, created a look that has been parodied and paid tribute to by everyone from The Simpsons to David Bowie. It works because it’s a uniform for a gang that has no ideology other than chaos. They aren't rebels with a cause. They’re just bored. In an era where "subcultures" are often just marketing demographics, the Droogs feel dangerously real. They represent the aimless aggression that bubbles up when society becomes too sterile or too indifferent.

Fact-Checking the Kubrick Legend

There are a lot of myths about the production.

🔗 Read more: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

- Did Malcolm McDowell really scratch his cornea? Yes. During the filming of the conditioning sequence, the specula (the eye-locks) actually scratched his eyes, and he was temporarily blinded. The doctor standing next to him in the scene was a real doctor, tasked with dropping saline into his eyes so they wouldn't dry out.

- Was the film banned? Not technically by the government in the UK. Kubrick asked Warner Bros. to withdraw it because he was receiving death threats and was disturbed by the press coverage.

- Is the Nadsat language real? It’s a constructed slang (a "conlang") created by Burgess, mixing Russian loanwords with Cockney rhyming slang. "Horrorshow" comes from the Russian "khorosho" (good). It’s designed to make the reader/viewer feel like an outsider.

Assessing the Legacy

Honestly, watching A Clockwork Orange film today is a different experience than it was in 1971. We are more desensitized to violence now, but the film’s portrayal of state overreach feels more relevant than ever. In a world of algorithms, targeted psychological profiling, and "cancel culture," the idea of "socially engineering" someone into being a good citizen isn't science fiction anymore. It’s a Tuesday.

The film remains a masterpiece of cinematography. John Alcott’s lighting—using mostly practical lamps and a lot of "bounce" light—gives it a surreal, high-contrast look that has aged remarkably well. It doesn't look like a "70s movie." It looks like a Kubrick movie.

How to Approach a Rewatch

If you’re going back to the Korova Milkbar, pay attention to the perspectives. Notice how the camera moves. Kubrick uses the wide-angle "fisheye" lens to distort the edges of the frame, making the world feel claustrophobic even in large rooms. It makes you feel trapped, just like Alex.

Practical Steps for Deeper Understanding:

- Read the 21st Chapter: Find a UK edition or the "Restored" version of the book. Compare how you feel about Alex when he "grows out" of his violence versus when he is "cured" of it.

- Listen to the Soundtrack Separately: Wendy Carlos’s work on the Moog is a landmark in electronic music history. It’s worth hearing without the visuals to appreciate the complexity of the arrangements.

- Research the "Copycat" Claims: Look into the 1970s British press coverage. It’s a fascinating study in moral panic and how media can be used as a scapegoat for systemic social issues.

- Watch "A Life in Pictures": This documentary provides excellent context on Kubrick’s working style during this specific period, which was perhaps his most creatively autonomous.

The film isn't meant to be liked. It’s meant to be reckoned with. It’s a cold, hard look at the darker parts of the human soul and the even darker parts of the systems that try to control it. Whether you find it a work of genius or a piece of pretentious filth, you can't deny that it’s impossible to ignore. That is the hallmark of truly great cinema.

Next time you see that iconic eye-staring poster, remember: it’s not just an image. It’s a warning.