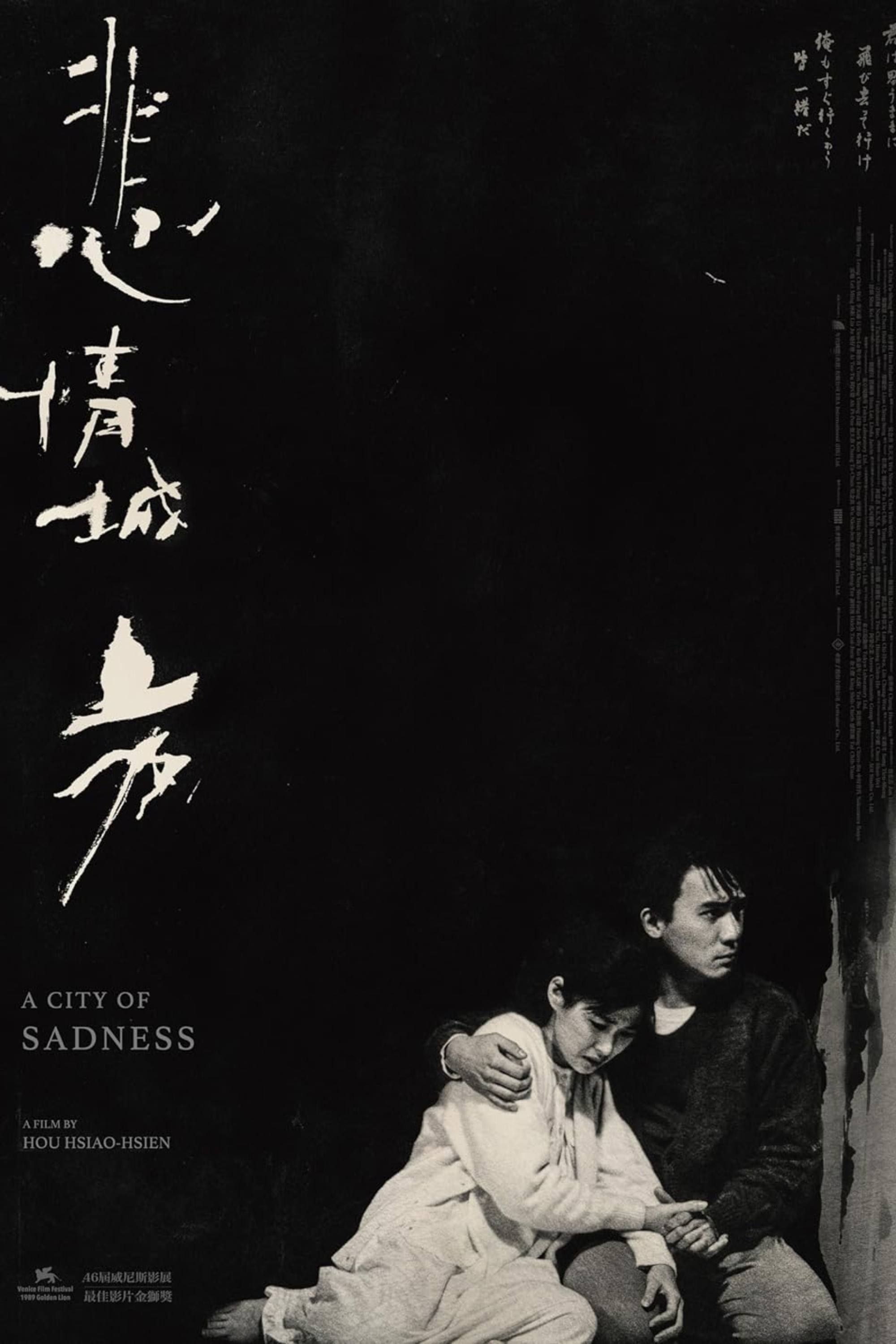

History is usually written by the winners. But in the case of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s 1989 masterpiece, A City of Sadness movie, history was written by the silent.

It’s a heavy film. Honestly, calling it "heavy" feels like an understatement. It’s a sprawling, intimate, and often confusing look at a family caught in the meat grinder of the 20th century. Specifically, it tackles the "White Terror" and the February 28 Incident in Taiwan. For decades, you couldn't even talk about these events in public without risking prison—or worse. Then this movie comes along and wins the Golden Lion at Venice. It changed everything.

You’ve probably seen plenty of war movies. Most of them focus on the explosions or the heroics. Hou doesn't care about that. He focuses on the dinner table. He focuses on the way a deaf-mute photographer, played by a very young Tony Leung Chiu-wai, tries to navigate a world where speaking the wrong language can get you killed. It's a film about what happens when the smoke clears and the bureaucracy of trauma begins.

The 2-28 Incident: What Really Happened

To understand why A City of Sadness movie is such a massive deal, you have to understand the context. In 1945, Japan surrendered. Taiwan, which had been a Japanese colony for 50 years, was handed back to the Chinese Nationalists (KMT). People were excited. They thought they were being "liberated."

They weren't.

Tensions boiled over on February 27, 1947, when colonial agents beat a widow selling unlicensed cigarettes in Taipei. The next day—February 28—protests erupted. The KMT response was brutal. Thousands were killed. Thousands more "disappeared" in the following years. This is the "February 28 Incident." For forty years, it was a taboo. A ghost.

Hou Hsiao-hsien didn't make a documentary. He made a family drama. We follow the Lin brothers. One is a black marketeer. One is a doctor who went missing in the war. One is a translator. And then there's Wen-ching (Tony Leung), the photographer. By viewing this massive, terrifying political shift through the lens of a single, fracturing family, the movie makes the history feel visceral. It’s not a textbook. It’s a wound.

Why Tony Leung Doesn't Speak

Here is a bit of movie trivia that’s actually meaningful: Tony Leung’s character is deaf and mute because Leung couldn’t speak Taiwanese or Japanese.

Hou Hsiao-hsien had a problem. He had this incredible actor from Hong Kong, but Leung’s lack of local dialect would have ruined the realism. So, Hou made the character unable to speak. It ended up being a stroke of genius. Wen-ching’s silence becomes a metaphor for the entire Taiwanese population under the KMT’s martial law. They were silenced. They had to communicate through notes, through glances, through the clicking of a camera shutter.

There is a scene in A City of Sadness movie where Wen-ching is on a train. A group of men confronts him. They ask him where he’s from. They’re looking for "outsiders" or "spies." Because he can’t answer quickly in the right dialect, they assume he’s the enemy. He finally manages to utter a few broken words: "I... am... Taiwanese."

🔗 Read more: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

It’s heartbreaking. It’s also incredibly tense. It captures that specific terror of a society where your identity is a life-or-death gamble.

The Style: Long Takes and "Empty" Space

If you’re used to Marvel movies or fast-paced thrillers, this film might frustrate you at first. Hou uses a lot of "static" shots. The camera rarely moves. He loves the long take.

He often places the camera in a hallway or outside a room. You watch the characters move in and out of the frame. Sometimes, the most important action happens off-screen. You hear a gunshot. You hear a scream. But the camera stays on a quiet landscape or a bowl of rice.

Why do this?

Because that’s how life feels during a transition of power. You don't always see the "big" moments. You just see the empty chairs they leave behind. This style, often called "New Taiwanese Cinema," was pioneered by Hou and his contemporary Edward Yang. They wanted to strip away the melodrama of traditional Chinese cinema. They wanted it to feel like life.

The movie is long—about 157 minutes. It demands patience. You have to sit with the sadness. You have to feel the passage of time. Honestly, it's a bit of a marathon, but the payoff is a sense of atmospheric immersion that few other films achieve.

The Language Barrier is the Story

Taiwan in the late 1940s was a linguistic mess. Older people spoke Japanese and Taiwanese. The new government spoke Mandarin. Some spoke Cantonese or Hakka.

In A City of Sadness movie, you hear all of these. The confusion is intentional. When the Nationalists arrive, they demand everyone speak Mandarin. Imagine being told, overnight, that the language you’ve spoken your whole life is now the language of the "enemy" or the "ignorant."

This linguistic friction is the engine of the movie’s conflict. It highlights the colonial nature of the KMT's arrival. They weren't just "taking back" Taiwan; they were imposing a new culture on a people who had already spent 50 years carving out their own hybrid identity.

💡 You might also like: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

The Controversy and the Legacy

When the film was released in 1989, martial law had only been lifted for two years. The wounds were fresh. People were terrified that the government would censor it or ban it.

Instead, it became a cultural phenomenon.

It forced the public to acknowledge the 2-28 Incident. It gave people a vocabulary for their grief. Before this, the tragedy was something whispered about in kitchens. After A City of Sadness movie, it was on the big screen. It won the top prize at Venice, making it the first Chinese-language film to do so. This international recognition made it harder for the Taiwanese government to suppress it.

It’s often cited as the first part of Hou’s "history trilogy," followed by The Puppetmaster (1993) and Good Men, Good Women (1995). Together, these films act as a collective memory for a nation that was forced to forget its own past.

Is it Actually Sad?

The title isn't a lie.

It is a deeply melancholic film. But it’s not "misery porn." It’s not trying to make you cry with cheap tricks or swelling violins. The sadness comes from the inevitability of change and the way ordinary people get trampled by the "Great Men" of history.

There’s a specific kind of beauty in it, too. The cinematography by Chen Huai-en is stunning. The misty mountains of Jiufen—where the movie was filmed—provide a ghostly, ethereal backdrop. Jiufen used to be a dying gold-mining town. After this movie, it became a massive tourist destination. People wanted to see the stairs where the characters walked. They wanted to feel that history.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often call this a "political" movie.

Sure, it is. But if you watch it only for the politics, you miss the point. It’s a movie about family dynamics. It’s about how a father reacts when his sons go astray. It’s about the quiet strength of the women—like Hinomi—who have to keep things running while the men are busy dying or going to jail.

📖 Related: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

Another misconception is that it’s "anti-Chinese." It’s not. It’s anti-authoritarian. It critiques the specific cruelty of the KMT administration during that era, but it does so by showing the humanity of everyone involved. Even the "villains" are often just cogs in a machine they don't understand.

Common Questions About Watching It

Where can I watch it?

It’s actually notoriously hard to find in high quality for a long time. However, a 4K restoration was released recently (around 2023 in some territories). Check specialized Criterion-style streamers or boutique Blu-ray labels. Don't settle for a grainy YouTube rip if you can help it; the lighting is too important.

Do I need to know Taiwanese history first?

It helps to know what "2-28" is, but the movie explains the feeling of it better than a Wikipedia page ever could. Just know that the transition from Japanese rule to KMT rule was messy and violent.

Is Tony Leung really that good in it?

Yes. He has no dialogue, yet he carries the emotional weight of the film. His performance is a masterclass in using your eyes and your presence to tell a story.

Actionable Steps for Film Buffs

If you’re planning to dive into A City of Sadness movie, don't just put it on in the background while you’re scrolling on your phone. You’ll get lost within ten minutes.

- Print out a family tree. Seriously. The Lin family is big, and because the film jumps around in time and doesn't hold your hand, it’s easy to forget which brother is which.

- Watch it in a dark room. Hou’s use of natural light and shadow is legendary. If there’s a glare on your screen, you’ll miss the subtle movements in the corners of the frame.

- Read up on the February 28 Incident. Spend five minutes on the basic timeline. It will make the "news" reports heard on the radio in the film much more impactful.

- Listen to the score. Naoko Terashima’s main theme is haunting. It’s simple, repetitive, and perfectly captures the cyclical nature of grief.

A City of Sadness movie isn't just a piece of entertainment. It’s an act of bravery. It’s a director standing up and saying, "We remember." In a world where history is constantly being sanitized or rewritten, we need films like this to remind us of the cost of silence.

If you want to understand modern Taiwan—and why its identity is so fiercely guarded today—you have to start here. It’s not an easy watch, but it’s an essential one. Grab some tea, put your phone away, and let the mist of Jiufen settle over you.

After you finish, look into the works of Edward Yang, specifically A Brighter Summer Day. It covers a similar era but from a different perspective, focusing on the children of the mainlanders who fled to Taiwan. Between these two films, you’ll get a clearer picture of 20th-century history than any textbook could provide.

Don't let the "slow cinema" label scare you off. The payoff is a profound connection to a past that almost stayed buried forever.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge:

- Locate the 4K Restoration: Seek out the recent digital restoration to ensure you're seeing the color grading and shadow detail as Hou Hsiao-hsien intended.

- Research the "White Terror": To better understand the stakes of the film's second half, read about the period of martial law that lasted from 1949 to 1987.

- Explore the New Taiwanese Cinema Movement: Look for interviews with screenwriter Chu T’ien-wen, who was a frequent collaborator with Hou and played a massive role in shaping the film's literary depth.