Stephen Hawking didn't want to write a textbook. He wanted to write the kind of book people would actually buy at an airport. He succeeded, mostly. In 1988, A Brief History of Time hit the shelves and basically broke the publishing world. It stayed on the London Sunday Times bestseller list for a staggering 237 weeks. That's over four years. People bought it in droves. They put it on their coffee tables. They carried it on subways.

But here is the dirty little secret about this masterpiece: hardly anyone actually finishes it.

It’s often called "the most unread book of all time." It’s brilliant, sure, but it’s also dense. You start with the cute anecdote about the lady who thinks the world is a tower of turtles, and by chapter nine, you’re drowning in imaginary time and the sum over histories. It’s a wild ride. Hawking’s goal was simple—explain where the universe came from and where it’s going without using a single equation. Well, he used one: $E=mc^2$. His editors warned him that every equation would halve his sales. He listened.

The Gamble That Made Hawking a Pop Culture Icon

Before 1988, Stephen Hawking was already a legend in the physics community. He’d done the math on black holes. He’d shown they weren't totally black because of what we now call Hawking Radiation. But he wasn't a household name. He needed money. Specifically, he needed to pay for his daughter’s school fees and the mounting costs of his 24-hour nursing care as his ALS progressed. He took a massive gamble on a popular science book.

He didn't just go to an academic press. He went for Bantam Books, a mass-market giant. He wanted the reach.

The editing process was brutal. Peter Guzzardi, his editor, kept pushing back. He told Hawking to make it clearer. He told him to stop assuming the reader had a PhD in theoretical physics. Hawking was notoriously stubborn, but he actually listened. He rewrote. He simplified. He tried to explain the "Big Bang" and "Light Cones" in ways that a non-scientist could visualize.

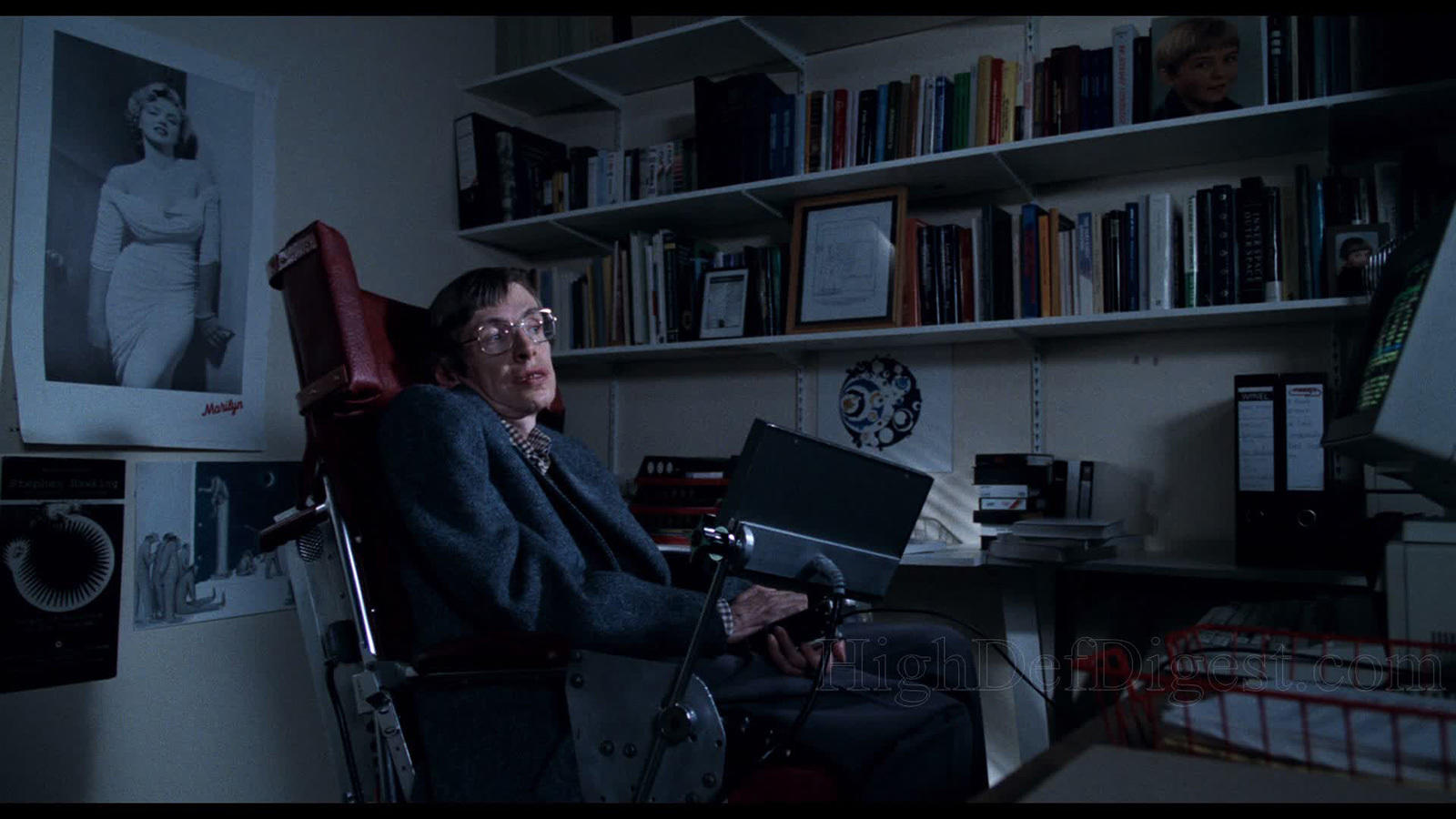

The result was a cultural phenomenon. Suddenly, a man in a wheelchair who could only communicate through a computer was the face of the universe. It changed how we look at scientists. They weren't just guys in lab coats anymore; they were explorers of the mind.

👉 See also: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

What A Brief History of Time Actually Tells Us

The book covers a lot of ground. It starts with our old-school views of the cosmos—Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus—and moves fast. It’s basically a roadmap of how we stopped thinking the Earth was the center of everything and started realizing we're on a tiny speck in an expanding void.

One of the big takeaways is the Arrow of Time. Why do we remember the past but not the future? Why does a cup of coffee get cold, but a cold cup never spontaneously gets hot? Hawking ties this to entropy. The universe is moving from order to disorder. That’s the thermodynamic arrow. Then there’s the psychological arrow—how we perceive time—and the cosmological arrow, which is the direction in which the universe expands.

Then there are the black holes. This was Hawking’s bread and butter.

He explains that black holes aren't just cosmic vacuum cleaners. They have a temperature. They leak. Over billions of years, they evaporate. This was a massive shift in physics because it combined General Relativity (the big stuff) with Quantum Mechanics (the tiny stuff).

The Mystery of the No-Boundary Proposal

This is where the book gets really "out there." Hawking and Jim Hartle proposed the No-Boundary Proposal.

Imagine the Earth. If you travel north, you eventually reach the North Pole. But what’s north of the North Pole? Nothing. It’s not that there’s a wall or a cliff; it’s just that the dimension of "north" ends there. Hawking suggested that time might be the same way at the moment of the Big Bang. Instead of a "beginning" where a finger pushed a button, time might just be a curved surface with no edge.

✨ Don't miss: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

It’s a mind-bending thought. It suggests the universe is completely self-contained. No creator required, at least not in the traditional sense of someone starting a clock.

Why People Struggle to Finish It

Let's be real. It's hard.

Hawking’s prose is lean. He doesn't waste words. This sounds great, but it means if you miss one sentence, you might lose the thread of the entire next chapter. You’re reading about the "Uncertainty Principle," and suddenly you’re expected to understand how that relates to "Particle Spin."

By the time you get to Wormholes and Time Travel, your brain is usually fried.

I think the "unread" reputation comes from the fact that the book is deceptive. It looks thin. It looks approachable. But it’s heavy. It’s like a shot of espresso—small, but it packs enough punch to keep you up all night questioning your existence.

The Legacy of the Brief History in 2026

We're decades removed from the original release, but the core of the book still holds up. We’ve actually photographed a black hole now—the one in the M87 galaxy. We’ve detected gravitational waves, something Hawking talked about as a consequence of Einstein’s work.

🔗 Read more: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

The book paved the way for everyone from Neil deGrasse Tyson to Brian Cox. It proved there was a market for "hard" science explained for the masses. It turned the mystery of the cosmos into a conversation.

Critics sometimes argue that the book is outdated. Some of the theories on "Superstrings" have evolved. Our measurements of the Hubble Constant (the speed the universe is growing) have gotten way more precise. But the spirit of the book—the idea that the universe is governed by a set of laws we can actually understand—is still the gold standard.

Common Misconceptions

- It’s a book about God. Not really. Hawking mentions the "mind of God" in the last sentence, but he later clarified he meant that metaphorically. He was looking for a "Theory of Everything" that explains the universe without needing supernatural intervention.

- You need a math background. You don't. You just need a lot of patience and maybe a search engine open next to you to look up some of the weirder concepts.

- It’s only for scientists. Honestly, it’s more for philosophers. It’s about our place in the timeline of everything.

How to Actually Read A Brief History of Time

If you want to actually get through it this time, don't read it like a novel. You can't binge-watch this book.

Read one chapter. Then stop. Walk around. Think about the fact that time is relative and that if you flew to a black hole and back, everyone you know would be dead while you only aged a few weeks. Let that sink in.

- Start with the pictures. There are illustrated versions of the book. Get those. The visuals of light cones and curved space make a world of difference.

- Skip the foreword if you have to. Dive straight into the "Our Picture of the Universe" chapter.

- Don't get hung up on "Imaginary Time." Even many physicists find that part a bit "math-magic." Just accept it as a tool Hawking used to make the equations work.

- Watch the 1991 documentary. Errol Morris made a film with the same title. It’s not a line-by-line adaptation; it’s more about Hawking’s life and the people around him. It provides great context.

A Brief History of Time isn't just a book; it's a testament to human curiosity. Here was a man who couldn't move a muscle, yet his mind was traveling to the beginning of time and the edge of the universe. It’s worth the struggle. Even if you only make it halfway through, you’ll come out the other side looking at the night sky differently.

To dive deeper into the science today, look up the latest James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) findings. Many of the things Hawking theorized about—the earliest stars and the formation of galaxies—are being photographed in high-def right now. Comparing Hawking’s 1988 predictions with 2026 imagery is the best way to see just how right (or interestingly wrong) he was. Check out the NASA exoplanet archive or the ESA’s Euclid mission updates to see the "History of Time" still being written in real-time.