It was supposed to be the "GTA Killer." Or at least, that’s what the schoolyard rumors and the edgy marketing campaigns back in 2006 wanted you to believe. If you were hanging around a GameStop or scrolling through early gaming forums in the mid-2000s, 25 to Life was this looming, controversial cloud. People were terrified of it. Politicians were lining up to condemn it before they’d even seen a loading screen. Then it actually came out, and... well, it was something.

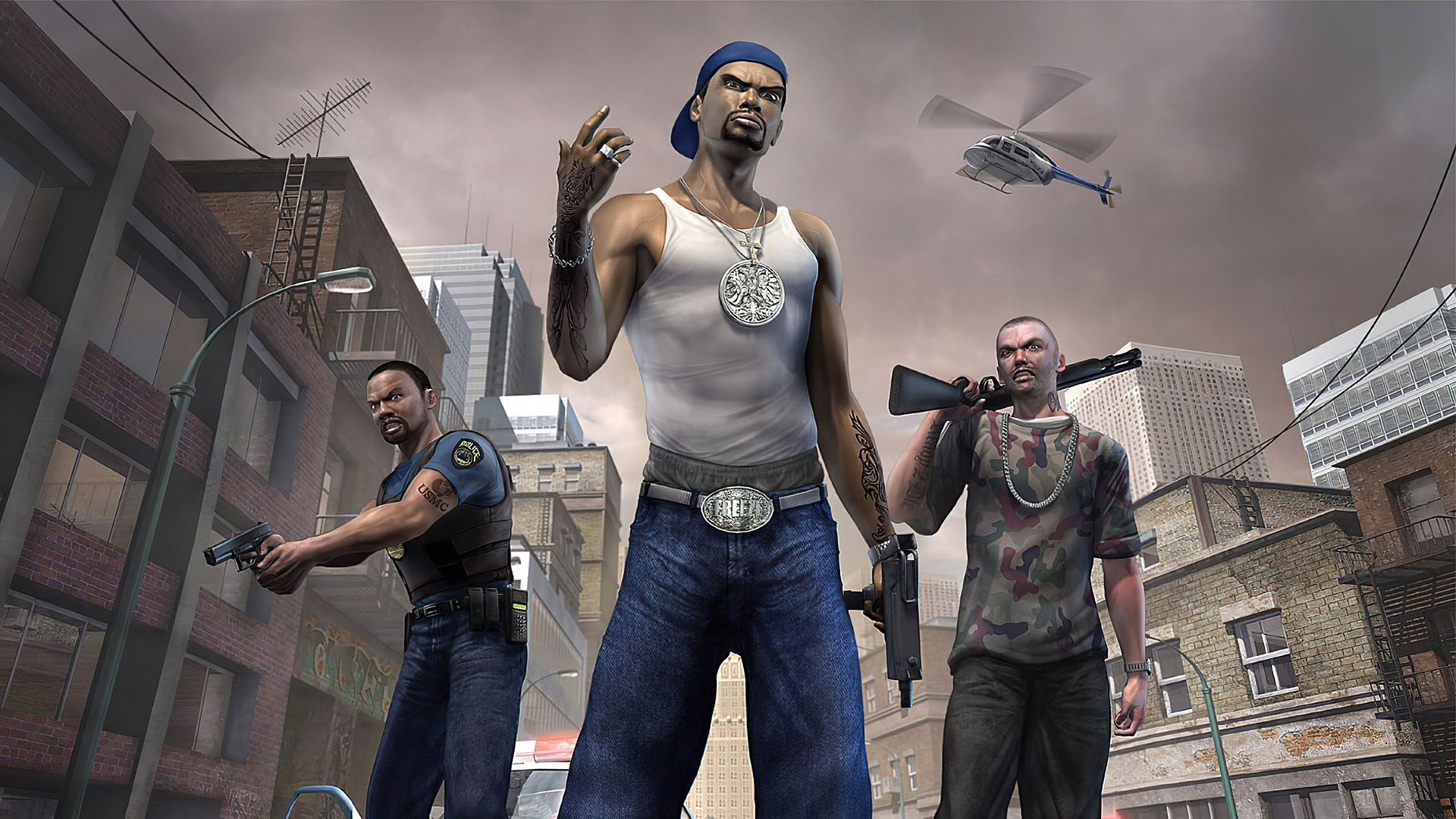

Honestly, looking back at 25 to Life today feels like opening a time capsule buried in a pile of baggy jeans and Ecko Unltd. hoodies. It’s a gritty, third-person shooter that tried to capture the "thug life" aesthetic of the era, splitting its narrative between a cop named Williams and a gangster named Freeze. It arrived at the absolute height of the moral panic surrounding video game violence. Senator Chuck Schumer famously called for a ban on the game, labeling it "sick" and "disturbing" because it allowed players to shoot law enforcement officers.

But here’s the thing: the controversy was way more interesting than the game itself.

The Hype vs. The Harsh Reality

Development was a bit of a mess. Originally handled by Highway 1 and eventually finished by Avalanche Software (the folks who, ironically, just gave us Hogwarts Legacy), the game suffered from constant delays. By the time it hit shelves on the PS2, Xbox, and PC, the "Urban Crime" genre was already getting crowded. True Crime: Streets of LA had already done the cop/criminal split. San Andreas had already mastered the hood epic.

25 to Life felt dated the second it arrived. The movement was stiff. The AI was—to put it nicely—clueless. You’d see SWAT team members running into walls while you peppered them with bullets from a Mac-10. It didn't matter that the soundtrack was actually pretty fire, featuring artists like DMX, Ghostface Killah, and Public Enemy. If the shooting doesn't feel good in a game about shooting, you've got a problem.

Yet, for some reason, we couldn't stop talking about it. The game represents a very specific moment in the mid-2000s where "edgy" was a business model. It wasn't enough to just have a good game; you needed a Parental Advisory sticker and a news segment on Fox News to move units.

Why the Multiplayer Was Actually Kinda Ahead of Its Time

Despite the single-player campaign being a short, clunky mess that you could breeze through in about four hours, the multiplayer was where the cult following started. This was the era of the burgeoning online console scene. 25 to Life offered 16-player matches that were surprisingly frantic.

It had a "Bank Robbery" mode that predated Payday by years. One team played the criminals trying to haul loot to a getaway van, while the other played the cops trying to stop the heist. It was chaotic. It was laggy. It was often unfair. But for a specific group of players who couldn't get Counter-Strike to run on their family PC, this was the closest they could get to tactical, objective-based team shooters on a console.

The customization was also a huge draw. You could swap out baggy jerseys, tattoos, and sneakers. In 2006, having that level of control over your avatar’s "street" look was actually a big deal. Most games back then just gave you a choice between "Generic Soldier A" and "Generic Soldier B."

The Schumer Effect: Marketing Through Outrage

We have to talk about the backlash. It’s impossible to discuss the legacy of 25 to Life without mentioning the political firestorm. In 2005, the gaming industry was under a microscope. Jack Thompson was a household name.

Senator Schumer and other critics focused on the "cop-killing" aspect. They argued that the game would desensitize kids and lead to real-world violence. Eidos Interactive, the publisher, basically leaned into it. They knew that nothing sells a game to a bored teenager like a politician telling them they aren't allowed to play it.

The irony? The game's story actually tries to have a "crime doesn't pay" message. Freeze, the main protagonist on the criminal side, is mostly trying to get out of the life to protect his family. It’s a cliché-ridden story, sure, but it wasn't the "murder simulator" the media made it out to be. It was just a mediocre shooter with a provocative coat of paint.

Technical Debt and the PS2 Era's End

Technologically, 25 to Life was a victim of its own long development cycle. It looked like an early PS2 game but was released right as the Xbox 360 was starting to show us what the next generation could do.

- The textures were muddy.

- Draw distances were abysmal (everything was covered in a "gritty" fog).

- The physics were non-existent—enemies would just crumple into canned death animations.

If you play it now—if you can even find a working copy and a console to run it—the flaws are glaring. The PC version is notorious for not playing nice with modern Windows OS without a dozen community patches. It’s a finicky piece of software.

📖 Related: The Super Mario Edition Switch: Why That Specific Red Console Still Holds Its Value

Looking Back: What Can We Learn?

What’s the takeaway here? Is 25 to Life a "hidden gem"? No. Not really. It’s a 5/10 game on its best day.

But it’s a fascinating case study in how a game's identity can be swallowed by its own marketing. It shows how the gaming industry used to rely on shock value before they realized that long-term engagement and polished mechanics were better for the bottom line. It also serves as a reminder of the "Urban" genre gold rush, where every publisher tried to capitalize on hip-hop culture, often with varying degrees of authenticity.

It's a weird relic. A loud, aggressive, somewhat broken relic that perfectly encapsulates the transition from the experimental 6th generation of consoles to the blockbuster 7th generation.

If You’re Curious About Playing It Today

If you actually want to experience this piece of gaming history, don't just go in blind. You’ll be disappointed. Instead, treat it like a digital museum exhibit.

1. Check the Soundtrack First

Before you spend money on a used disc, look up the tracklist on Spotify or YouTube. The music is genuinely the best part of the experience and captures the 2004-2006 hip-hop scene perfectly.

2. PC Modding is Mandatory

If you’re on PC, look for the widescreen fixes and frame rate limiters. The game’s logic is tied to its frame rate; if you run it too fast on a modern rig, the physics go haywire and the AI breaks even further.

3. Adjust Your Expectations

Don't compare it to Grand Theft Auto. Compare it to a low-budget action movie you'd find in a bargain bin at Blockbuster. It’s "B-movie" gaming at its finest.

4. Track Down the Physical Box Art

Part of the charm of 25 to Life was the aggressive, graffiti-laden packaging. If you’re a collector, the Xbox version is generally considered the "cleanest" way to play it if you have a compatible 360 or original hardware.

The era of games like this—mid-tier titles that swung for the fences with controversy—is mostly gone. Everything now is either a $200 million AAA behemoth or a stylized indie. There’s no room for a "25 to Life" in the modern market, and in a weird way, that makes it worth remembering. It was a messy, loud, flawed attempt at something that the industry eventually outgrew.