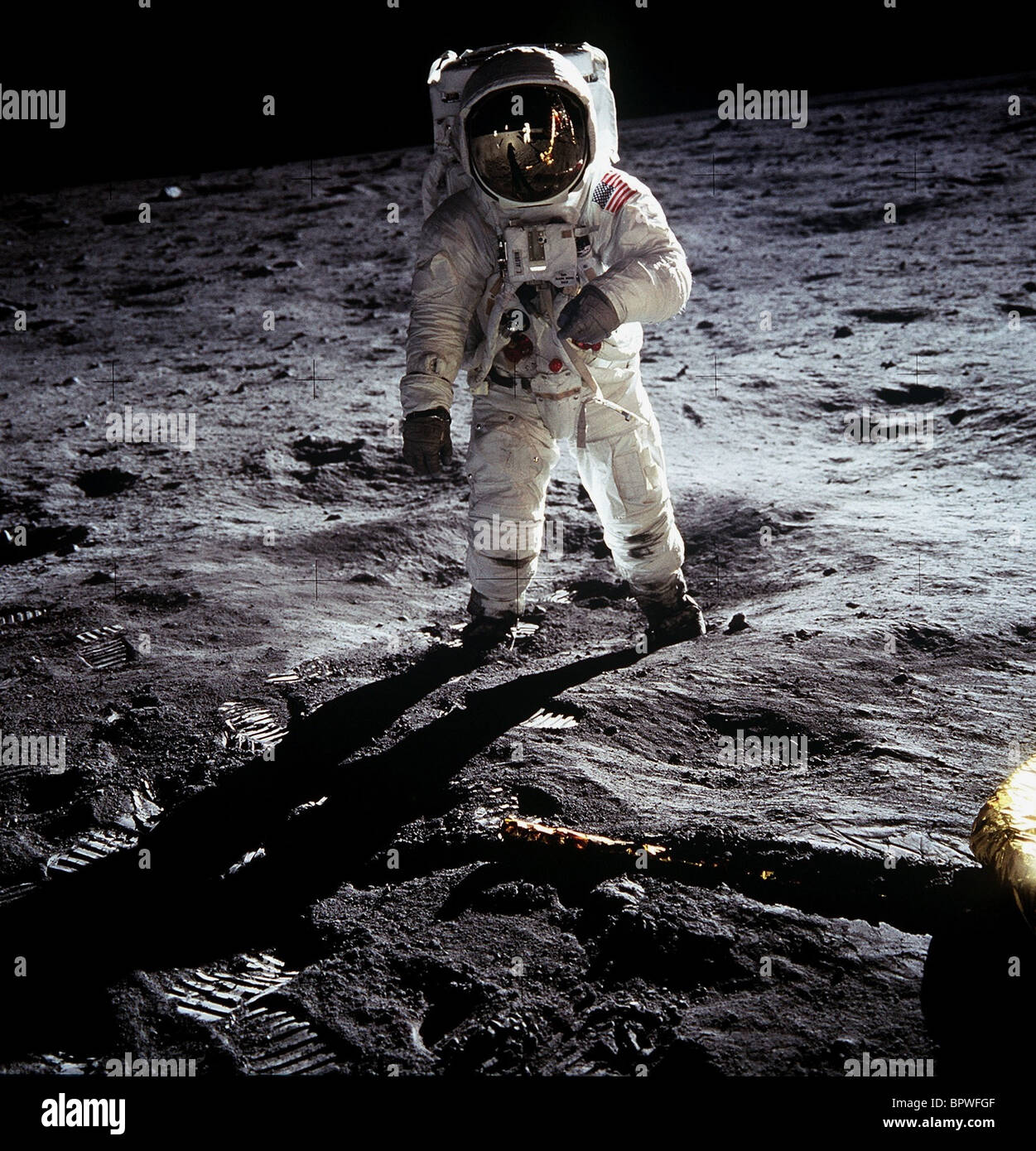

You’ve seen the one with Buzz Aldrin standing there, totally still, with Neil Armstrong reflected in his gold visor. It’s haunting. It is probably one of the most famous 1969 moon landing pictures ever taken, and yet, half the time, people forget Armstrong was the one behind the camera for most of that mission. He was the photographer. He was the guy making sure the history books had something to show.

The grainy, ghostly black-and-white footage we all remember from the live TV broadcast wasn't actually a "photo" in the traditional sense. It was a slow-scan television feed. But the high-resolution stills? Those were something else entirely. They were shot on medium-format Hasselblad cameras that had been stripped down to their bare essentials to save weight. Every ounce mattered when you were trying to break orbit.

Honestly, it’s a miracle they came out so well.

The Gear Behind the 1969 Moon Landing Pictures

NASA didn't just buy a camera off a shelf in 1969 and hope for the best. They worked with Hasselblad to create the Data Camera (HDC). It was basically a modified 500EL. They took out the viewfinder. They took out the mirror. Why? Because you can’t exactly put your eye to a viewfinder when you’re wearing a pressurized fishbowl on your head. You just point and pray.

The film was special, too. Kodak developed a thin-base polyester film that allowed the astronauts to take 160 color shots or 200 black-and-white shots per magazine. If you look closely at many 1969 moon landing pictures, you'll see tiny black crosses. Those are "reseau crosses." They were etched onto a Glass Plate (the Réseau plate) right in front of the film plane. Scientists used them to measure distances and heights in the photos later. They aren't "glitches" or "overlays." They are hard science etched into the frame.

Why do some photos look so "perfect"?

Critics sometimes point to the perfect framing of these shots as evidence of a hoax. That's a bit silly. The truth is that Armstrong and Aldrin practiced for hundreds of hours. They had cameras bracketed to their chests. They learned how to pivot their bodies to "aim" the lens. Plus, we only see the good ones. For every iconic shot, there are dozens of blurry, overexposed, or poorly framed rejects sitting in the archives at the Johnson Space Center.

The lighting on the lunar surface is incredibly harsh. There’s no atmosphere to scatter light. Shadows are pitch black. Highlights are blindingly bright. This is why the lunar modules look like they're sitting in a spotlight on a stage. It’s just how physics works without air.

🔗 Read more: Why Browns Ferry Nuclear Station is Still the Workhorse of the South

The Mystery of the Missing Neil Armstrong Photos

Here is a weird fact: there are almost no clear, full-body 1969 moon landing pictures of Neil Armstrong on the surface.

Think about that. The first man to walk on the moon, and we barely have a photo of his face. Most of the famous shots are of Buzz Aldrin. Why? Because Neil had the camera. He was the designated photographer for the bulk of the Extravehicular Activity (EVA). Buzz did take the camera for a short period, but he mostly took "panorama" sequences or shots of technical equipment.

There is one shot—AS11-40-5903—where you can see Armstrong working at the Modular Equipment Stowage Assembly (MESA). His back is to us. It’s blurry. It’s a bit of a letdown if you’re looking for a hero shot, but it’s real. It’s human.

The most famous "portrait" of the mission is the one of Aldrin standing near the leg of the Lunar Module. If you zoom into Aldrin’s visor, you can see the tiny white silhouette of Armstrong and the Eagle lander. That’s our best "selfie" of the 20th century. It wasn't planned to be iconic; it just happened because the sun was at the perfect angle.

The Cross-Hatch Controversy and Lighting Myths

People love a good conspiracy. One of the biggest talking points involves the shadows in the 1969 moon landing pictures. "Why aren't the shadows parallel?" they ask. "There must be multiple light sources, like a film studio!"

Well, no.

💡 You might also like: Why Amazon Checkout Not Working Today Is Driving Everyone Crazy

The moon isn't a flat, gray floor. It’s a landscape of craters, ridges, and slopes. If you shine a single light on a bumpy surface, the shadows will look "wonky" from certain perspectives. It’s basic perspective distortion. Also, the lunar soil (regolith) is retroreflective. It reflects light back toward the source, which acts like a giant fill-light, softening the shadows on the astronauts' suits.

Then there’s the "missing stars" argument. Why aren't there stars in the background of the 1969 moon landing pictures?

It’s about exposure. The moon is bright. The astronauts are wearing bright white suits. To capture detail on a bright object in the sun, you need a fast shutter speed. If you left the shutter open long enough to see the stars, the astronauts would look like glowing white blobs of overexposed light. It’s the same reason you don’t see stars in photos taken at night in a football stadium. The stadium lights are too bright.

How to Access the Real Archives Today

If you want to see these images without the compression of a social media post, you need to go to the source. NASA has digitized the original 70mm film magazines.

The Project Apollo Archive on Flickr is probably the best place for a casual browse. It contains thousands of raw scans. You’ll see the "accidental" shots—the ones of the cabin interior, the blurry lunar horizon, and the technical shots of the soil. Seeing the "bad" photos actually makes the "good" ones feel much more authentic.

- Magazine S (Color): Contains the famous shots of the Earth rising over the lunar limb.

- Magazine R (B&W): Focuses heavily on the descent and the initial steps.

- The "Greatest Hits": These are usually the ones found in Magazine AS11-40.

Moving Beyond the Still Image

The 1969 moon landing pictures gave us a sense of place, but the 16mm Maurer Data Acquisition Camera (DAC) gave us movement. This camera was mounted in the window of the Lunar Module. It captured the descent. It captured the "one small step."

📖 Related: What Cloaking Actually Is and Why Google Still Hates It

When you watch the 16mm footage alongside the still photos, the technical reality of the mission starts to click. You see the dust kicking up. You see the RCS thrusters firing. It wasn't a movie set; it was a cramped, vibrating, terrifyingly fragile piece of engineering.

To truly understand these photos, you have to look at them as technical documents first and art second. They were meant to record where the rocks came from. They were meant to document the footprint depth to see how much weight the surface could hold. The fact that they are beautiful is almost a side effect of the incredible clarity of space.

Analyzing the Impact

The legacy of these images isn't just about "winning the Space Race." They changed how we see ourselves. Before 1969, we didn't really have a collective "family photo" of humanity. Then, suddenly, we had pictures of a small, fragile blue marble hanging in a void.

It shifted the environmental movement. It changed philosophy. And it all came down to a few guys with modified Swedish cameras and a lot of training.

If you’re interested in diving deeper into the technical side of these photos, you should look up the work of Kipp Teague. He’s the guy who spent years meticulously scanning and restoring these images for the public. His work at the "Apollo Archive" is the gold standard for anyone who wants to see the 1969 moon landing pictures as they were meant to be seen.

To get the most out of these historical artifacts, start by downloading the high-resolution TIFF files from the official NASA archives rather than relying on JPEG versions found on blogs. Study the "unprocessed" versions to see the true colors of the lunar surface—which is actually more of a tan/brown-grey than the stark "TV grey" we often imagine. Finally, compare the 1969 photos with the LRO (Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter) images taken in recent years. You can actually see the descent stages and the astronaut paths still visible in the dust from orbit, confirming the exact locations where those iconic 1969 stills were captured.