Look at a handful of 1939 World's Fair photos and you’ll notice something immediately weird. Everyone is wearing wool coats and fedoras, looking very "Great Depression," yet they are standing in front of buildings that look like they were ripped out of a 21st-century sci-fi movie. It’s a jarring contrast. You have the dusty reality of the late 1930s clashing head-on with the "World of Tomorrow" promised by the fair’s organizers. Honestly, these images are probably the most important visual records we have of how a generation, beat down by economic collapse, desperately tried to imagine a way out.

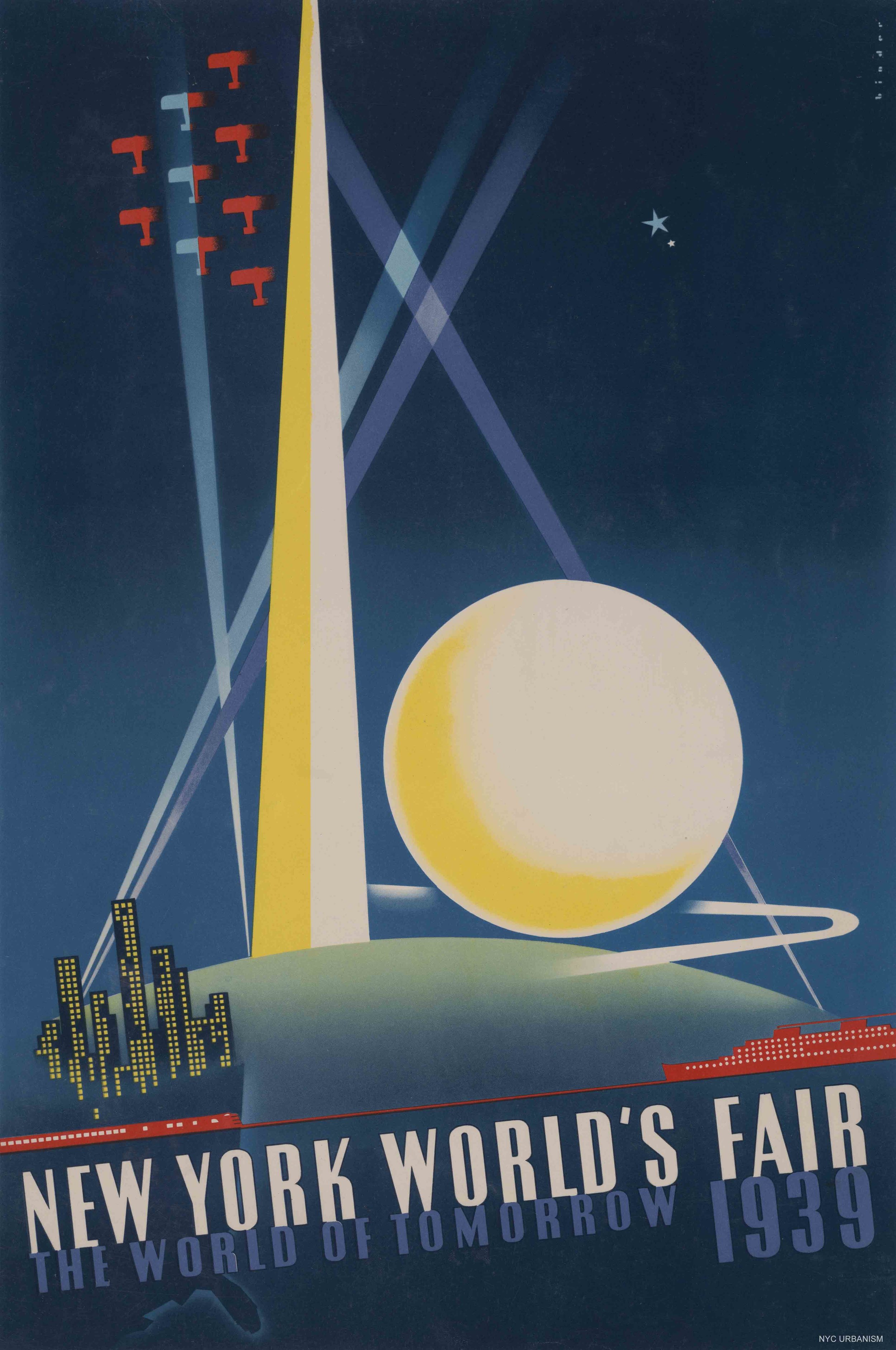

The fair was held at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in Queens. Before it was a global landmark, it was literally a giant ash heap. F. Scott Fitzgerald called it the "valley of ashes" in The Great Gatsby. But by 1939, it was home to the Trylon and Perisphere. Those two massive, white geometric shapes are the stars of almost every vintage postcard and snapshot from the era. The Trylon was a 700-foot spire, and the Perisphere was a massive globe that housed "Democraticity," a diorama of a future utopia.

What the 1939 World's Fair Photos Actually Reveal

When you dig into archives—like the massive collection at the New York Public Library or the images captured by Gottscho-Schleisner—you see more than just architecture. You see hope. It sounds cheesy, but it’s true. People weren't just taking photos of cool buildings; they were documenting the first time they ever saw a television.

RCA had a pavilion there. David Sarnoff, the head of RCA, stood in front of a camera and broadcast the fair’s opening to a tiny handful of receivers in New York City. If you find the right 1939 World's Fair photos, you can see the crowds huddled around these small, flickering screens. They weren't seeing 4K resolution. It was grainy, green-tinted, and small. But to them? It was magic.

The lighting was another thing. This was one of the first major events to use fluorescent lamps on a massive scale. At night, the fairgrounds didn't look like a 1930s city. They glowed with vibrant, neon-adjacent colors that had never been seen in nature or urban life before. This is why the night photography from the fair is so sought after by collectors today. The long exposures required back then meant the people often look like ghosts, blurred while moving through a static, glowing wonderland.

The Westinghouse Time Capsule and the Robot

You've probably heard of "Elektro." He was a seven-foot-tall silver robot built by Westinghouse. He could smoke a cigarette, which is objectively hilarious for a robot, and say about 70 words. In photos, he looks like a giant tin can with a human face. But he represented the peak of 1939 technology.

🔗 Read more: Anime Pink Window -AI: Why We Are All Obsessing Over This Specific Aesthetic Right Now

Alongside Elektro, Westinghouse buried a time capsule. It wasn't supposed to be opened for 5,000 years. They filled it with things like a Mickey Mouse watch, a pack of Camels, and a newsreel. When we look at these photos now, we’re essentially looking at the "user manual" for that capsule. We are seeing the context of what those people thought was worth saving for the year 6939.

The Darker Side of the "World of Tomorrow"

It wasn't all robots and neon. Look closely at the background of 1939 World's Fair photos and you’ll see the shadows of World War II. The fair opened in April. By September, Germany had invaded Poland.

The Polish Pavilion is a haunting example. When the fair started, it was a proud display of Polish culture and art. By the time the 1940 season of the fair rolled around (it ran for two years), Poland as a sovereign nation had effectively ceased to exist. The staff at the pavilion were suddenly refugees in Queens. They couldn't go home. They kept the pavilion open as a symbol of defiance.

There's a famous set of photos showing the "Peace and Freedom" speech by Albert Einstein at the fair. He was there to talk about cosmic rays, but the subtext was clearly the impending collapse of European peace. You can see it in the faces of the dignitaries. They weren't just looking at the future; they were watching the present fall apart.

Why These Photos Rank So High for Collectors

Collectors go nuts for original Kodachrome slides. Kodachrome was still relatively new in 1939. Most people were still shooting in black and white. If you find a true color 1939 World's Fair photo, the colors are incredibly saturated. The reds are deep, and the blues of the sky over Queens look almost artificial.

💡 You might also like: Act Like an Angel Dress Like Crazy: The Secret Psychology of High-Contrast Style

These slides are rare. Most people used Brownie cameras or other cheap folding cameras that took small, grainy black-and-white snapshots. A professional-grade color slide from 1939 is like a time machine that hasn't faded. It makes the "World of Tomorrow" feel like it happened last week.

- The General Motors Futurama Exhibit: This was the most popular attraction. People waited in line for hours to sit in moving chairs and look down at a massive model of what America would look like in 1960. It predicted the interstate highway system.

- The Food Zone: Yes, they had a zone dedicated to food technology. Continental Baking Company had a building that looked like a giant Hostess cake box.

- The Lagoon of Nations: Every night, there was a show with water, fire, and music. It was the precursor to the Bellagio fountains in Las Vegas.

Finding and Identifying Authentic Photos

If you're hunting for these in antique shops or online, you need to be careful. A lot of what’s marketed as "original" are actually 1950s reprints or souvenir books.

Genuine snapshots from the fair usually have a specific size—often 2.5 by 3.5 inches. Look for the "official" stamp. Licensed photographers like Underwood & Underwood had the rights to sell professional prints on-site. These usually have a high-gloss finish and a printed caption on the back.

Amateur photos are often more interesting, though. They show the "messy" parts of the fair. The trash cans. The tired kids sitting on the curbs. The long lines for the Parachute Jump (which was later moved to Coney Island). These candid 1939 World's Fair photos tell the human story that the official PR shots tried to hide.

The Architecture of Tomorrow

The fair was basically the birthplace of "Streamline Moderne." Everything had rounded corners. Everything looked like it was moving fast, even if it was a stationary building.

📖 Related: 61 Fahrenheit to Celsius: Why This Specific Number Matters More Than You Think

The Ford Motor Company building featured a "Road of Tomorrow" where visitors could actually ride in new cars on an elevated track. It was a massive circular structure. Photos of this building are a masterclass in 1930s industrial design. It wasn't just about selling cars; it was about selling the idea that technology would solve all of our social problems.

Of course, we know now that it didn't. The "World of Tomorrow" was a bit of a lie, or at least a very optimistic guess. But that’s why the photos are so gripping. They capture a moment of pure, unadulterated belief in progress right before the world went through the meat grinder of the 1940s.

How to Use These Images Today

If you're a designer or a history buff, these images are a goldmine for inspiration. The color palettes—cream, teal, and "burnt orange"—are making a huge comeback in retro-futuristic design.

For researchers, the best place to go is the Digital Collections of the New York Public Library. They’ve digitized thousands of these images, including the work of Samuel Gottscho. He was the guy who captured the fair in its most dramatic, architectural glory.

Another tip: check the Library of Congress. They have the Farm Security Administration (FSA) archives. While the FSA photographers were mostly documenting the poverty of the South, a few of them ended up in New York and captured the fair from a much more critical, social-realist perspective.

Practical Tips for Organizing Your Collection

- Check for Light Leaks: Old cameras often had "bellows" that cracked. If you see orange or white streaks on an old photo, it's not a ghost—it's a light leak, which actually helps prove the photo's age.

- Date the Cars: If you see a photo and you're not sure if it's 1939 or 1964 (the other New York World's Fair), look at the cars. 1939 cars have high running boards and separate headlights. 1964 cars are low, wide, and have tailfins.

- Note the Landmarks: If you don't see the Trylon (the big needle), it might not be the 1939 fair. That structure was demolished and sold for scrap metal after the fair ended to help the war effort. It doesn't exist anymore.

The 1939 World's Fair was a fleeting moment. By the time the lights went out in October 1940, the world was a different place. The steel from the "Future" was literally melted down to make bombs and tanks for the "Present." That's why these photos feel so heavy. They aren't just pictures of a theme park. They are the last photographs of an era that thought it could invent its way out of trouble.

To truly appreciate this era, start by browsing the NYPL Digital Gallery specifically for the "Gottscho-Schleisner Collection." Compare the official promotional shots with the "Street Life" series to see how the average visitor experienced the grounds. If you're looking to buy, verify the paper stock; authentic 1939 prints should be on heavy, fiber-based paper, not the thinner resin-coated paper common after the 1960s. Checking the back for a "Velox" watermark is a quick way to confirm a print's vintage origin.