Ever stared at a portrait you drew and felt like something was... off? Not like "I forgot how to draw a nose" off, but more like the person’s head is somehow collapsing into itself. You’re likely wrestling with the 0.5 perspective drawing face, a specific, tricky angle that sits awkwardly between a direct front view and a full profile. It's that subtle turn—maybe just 15 to 30 degrees—where the features start to compress, but the back of the head hasn't fully revealed itself yet.

It’s frustrating.

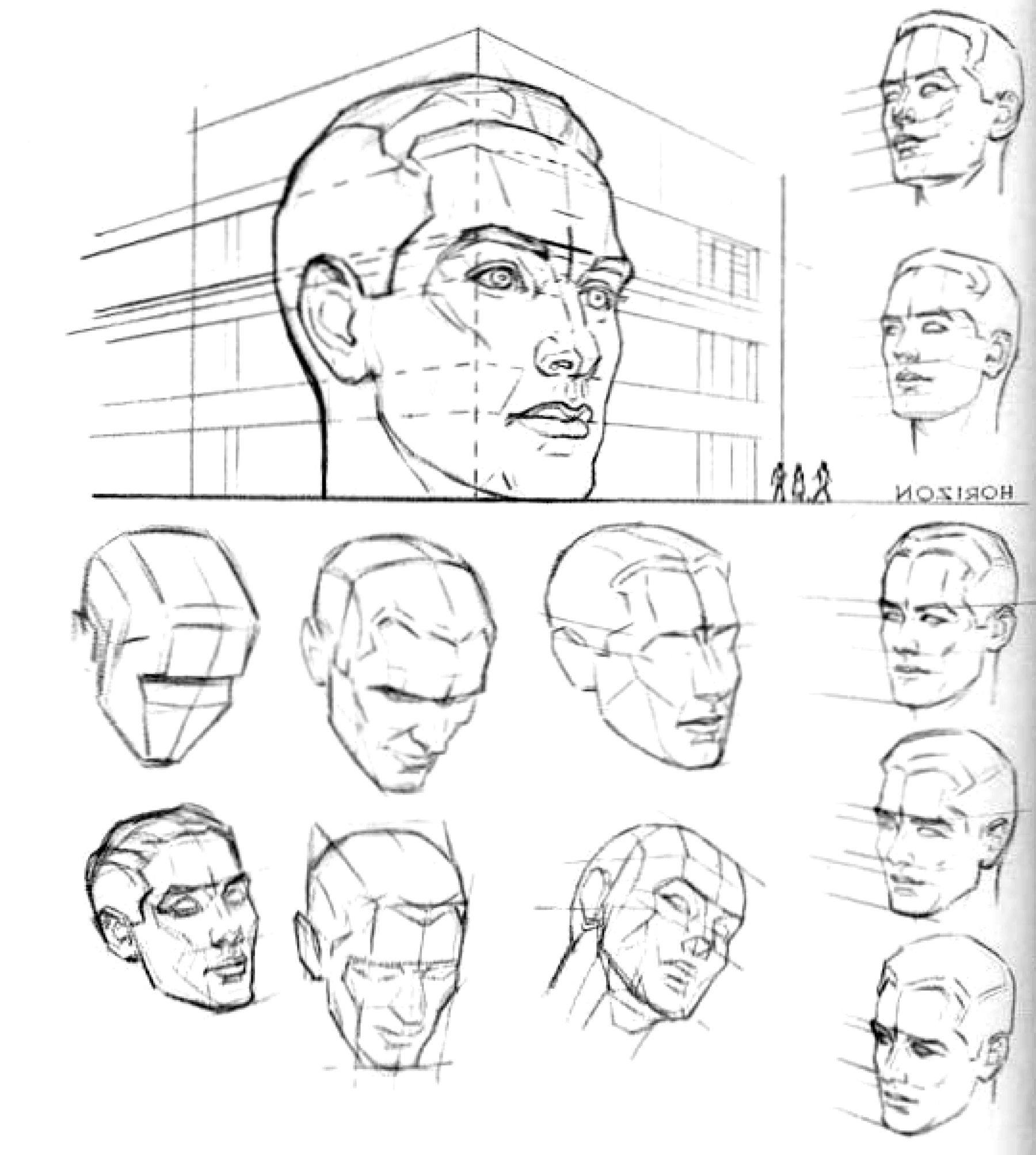

Most beginners learn the "Loomis Method" or "Reilly Abstraction" for the front, side, and three-quarter views. But the 0.5 perspective? That's the "uncanny valley" of portraiture. It’s a slight tilt that happens in candid photography all the time. If you don't nail the foreshortening on the "far" side of the face, your subject ends up looking like a Picasso painting—and not in the expensive, intentional way.

The math of a slight turn

Perspective isn't just for buildings. When a head rotates, every feature undergoes a transformation based on the curvature of the skull. In a 0.5 perspective drawing face, the centerline of the face (the ridge of the nose, the philtrum, the chin) moves away from the middle of the oval. But it doesn't move far.

Think about a cylinder. If you draw a line down the center and turn it slightly, that line becomes a curve. In this specific perspective, the eye further from the viewer doesn't just get smaller; it narrows horizontally. This is called foreshortening.

I’ve seen so many artists make the mistake of keeping both eyes the same width. Don't do that. The "far" eye should be significantly narrower because you're seeing it at an angle. If the "near" eye is an inch wide on your paper, the far eye might only be three-quarters of an inch. It’s a tiny difference that makes or breaks the realism.

Why the nose is your biggest enemy

In a full 3/4 view, the nose breaks the silhouette of the cheek. In a 0.5 perspective, it usually stays inside the boundary of the face. This is the danger zone. Because the nose is a protrusion, it overlaps part of the far eye or the far cheek.

Andrew Loomis, the legendary illustrator whose books like Drawing the Head and Hands are basically the bible for artists, emphasized the "corner" of the brow. In a 0.5 turn, you start to see the bridge of the nose masking the tear duct of the far eye. If you draw the whole far eye clearly, you’ve probably failed the perspective. You have to be brave enough to hide parts of the anatomy behind other parts.

✨ Don't miss: Sagres Bar and Grill Newark: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s about layers.

Also, the nostrils. Oh man, the nostrils. In this view, the "near" nostril is wide and open, while the "far" one is almost a flat line or completely hidden by the tip of the nose. Drawing both nostrils symmetrically is a one-way ticket to making your portrait look like a flat emoji.

Breaking the "symmetry" habit

Our brains are hardwired to see faces as symmetrical. It's an evolutionary thing—we check for health and genetic fitness by looking for balance. When you sit down to draw a 0.5 perspective drawing face, your brain is actively lying to you. It’s screaming, "The ears are level! The eyes are the same size!"

You have to ignore your brain.

Look at a photo of someone slightly turned. Take a ruler or a straight edge. Hold it up to the screen. You’ll notice the line connecting the pupils isn't horizontal anymore; it's slightly tilted. The ear on the far side is higher or lower depending on whether the head is tilted up or down.

Perspective is a grid. Even a 0.5 turn puts the face on a curved grid.

The "Far Side" Trap

The most common point of failure in a 0.5 perspective drawing face is the jawline. On the "near" side, the jaw follows a clear path from the chin to the ear. On the "far" side, the jawline often disappears behind the curve of the chin or the neck.

Actually, let’s talk about the cheekbone.

In this slight turn, the far cheekbone creates a very subtle bump in the silhouette. If you draw a smooth egg shape, it looks like a mannequin. If you exaggerate the bump, it looks like they have a localized allergic reaction. You’re looking for a "soft edge."

The distance between the far eye and the edge of the face is the "golden key" for this angle. In a front view, this distance is equal on both sides. In a 0.5 view, that gap on the far side shrinks significantly. Sometimes the eyelashes of the far eye will actually touch the edge of the facial silhouette.

Lighting is the ultimate cheat code

If you're struggling with the construction, use light to define the planes. This is where the "Asaro Head" comes in handy. For those who don't know, the Asaro Head is a simplified sculpture that breaks the human face into flat planes. It’s a literal lifesaver for understanding how light hits a 0.5 perspective drawing face.

When the head turns slightly, the "side" plane of the nose catches light differently than the "front" plane.

- Identify your light source.

- Determine the "terminator line"—that’s where light ends and shadow begins.

- In a 0.5 perspective, the far side of the face often falls into a "core shadow."

- Use a mid-tone to bridge the gap between the bright forehead and the shadowed temple.

Shadows follow the form. If your shadows are flat, your perspective will look flat, no matter how good your proportions are. Use the shadow under the nose (the "cast shadow") to show exactly how far out that nose is sticking. A long shadow suggests a sharp turn; a short, tight shadow suggests the face is still mostly facing you.

The Secret of the Mouth

People forget that the mouth isn't a flat sticker. It’s a wrap-around feature on a curved dental arch.

In a 0.5 perspective drawing face, the center line of the lips (the "cupid’s bow") is offset. The half of the mouth on the far side is "foreshortened"—it looks squashed. The corner of the mouth on the far side will be tucked away, while the near corner is fully visible.

Think of the teeth as a tuna can inside the mouth. When the can turns, the labels on the side get skinnier. Your lips are the labels.

Practical steps to master the slight turn

Don't just jump into a finished portrait. You'll get frustrated and quit. Instead, try these targeted exercises to get the 0.5 perspective into your muscle memory.

First, draw five "ghost heads." These are just basic ovals with a vertical centerline and a horizontal eye line. Turn them only slightly. Don't draw the features yet. Just focus on where that centerline goes. It should be a curve, like a longitude line on a globe.

Second, focus on the "mask" of the face. Draw the area from the brows to the bottom of the nose. At a 0.5 turn, this "mask" shifts. Practice drawing just the eyes and nose at this angle. Do it twenty times. It sounds boring, but it's how the pros do it.

Third, use a 3D model app. There are plenty of free ones like "Handy Art Reference" or even just looking at a 3D scan on Sketchfab. Rotate the head to that awkward 0.5 position. Take a screenshot. Draw over it. This isn't cheating; it's "calibrating your eyes." You need to see where the landmarks actually land versus where you think they land.

Finally, check your "negative space." Look at the shape of the air around the face. In a 0.5 perspective drawing face, the space between the nose and the edge of the cheek is a very specific shape. If you can draw that "empty" shape correctly, the nose will automatically be in the right place.

It’s all about un-learning the symbols we’ve used since kindergarten. A nose isn't a triangle; it's a volumetric wedge. An eye isn't a football shape; it's a sphere sitting inside a socket. When that sphere turns, the lids wrap around it.

Stop drawing what you think a face looks like. Start drawing the shapes created by the turn. That is the only way to master the 0.5 perspective.

Next time you’re sketching, try to find the "corner" of the forehead where it turns into the temple. In this perspective, that corner is your North Star. Everything else—the eyes, the ears, the jaw—aligns to that shift. Once you see it, you can't unsee it.

Actionable Next Steps:

Pick a reference photo where the subject is looking just slightly away from the camera. Lay a piece of tracing paper over it. Draw a vertical line following the bridge of the nose and a horizontal line through the eyes. Notice how the "cross" is curved and off-center. Now, try to replicate that "curved cross" on a blank sheet of paper and build a basic head around it, focusing strictly on making one side of the features narrower than the other.