Everyone asks the same thing. You see it on social media, you hear it at the dinner table, and you definitely see it plastered across every cable news ticker. Who’s winning the vote? It sounds like a simple question with a simple mathematical answer. But honestly, if the last few election cycles have taught us anything, it’s that "winning" is a slippery concept until the very last ballot is certified.

We live in an era of data saturation. We have high-frequency polling, needle-trackers, and "expert" modelers who treat elections like a weather forecast. Yet, when the dust settles, the gap between the predicted winner and the actual person taking the oath of office can be cavernous.

The Illusion of the Real-Time Winner

Right now, if you look at the aggregate data from sites like FiveThirtyEight or RealClearPolitics, you’re getting a snapshot of a moment that has already passed. That’s the first thing people get wrong. A poll isn't a prediction; it's a blurry polaroid of how a specific group of people felt last Tuesday.

When we talk about who’s winning the vote, we usually conflate three very different things:

- National Popular Support: Who has more fans across the entire country?

- The Electoral College Map: Who has the path to 270?

- Momentum: Who is gaining ground in the final 72 hours?

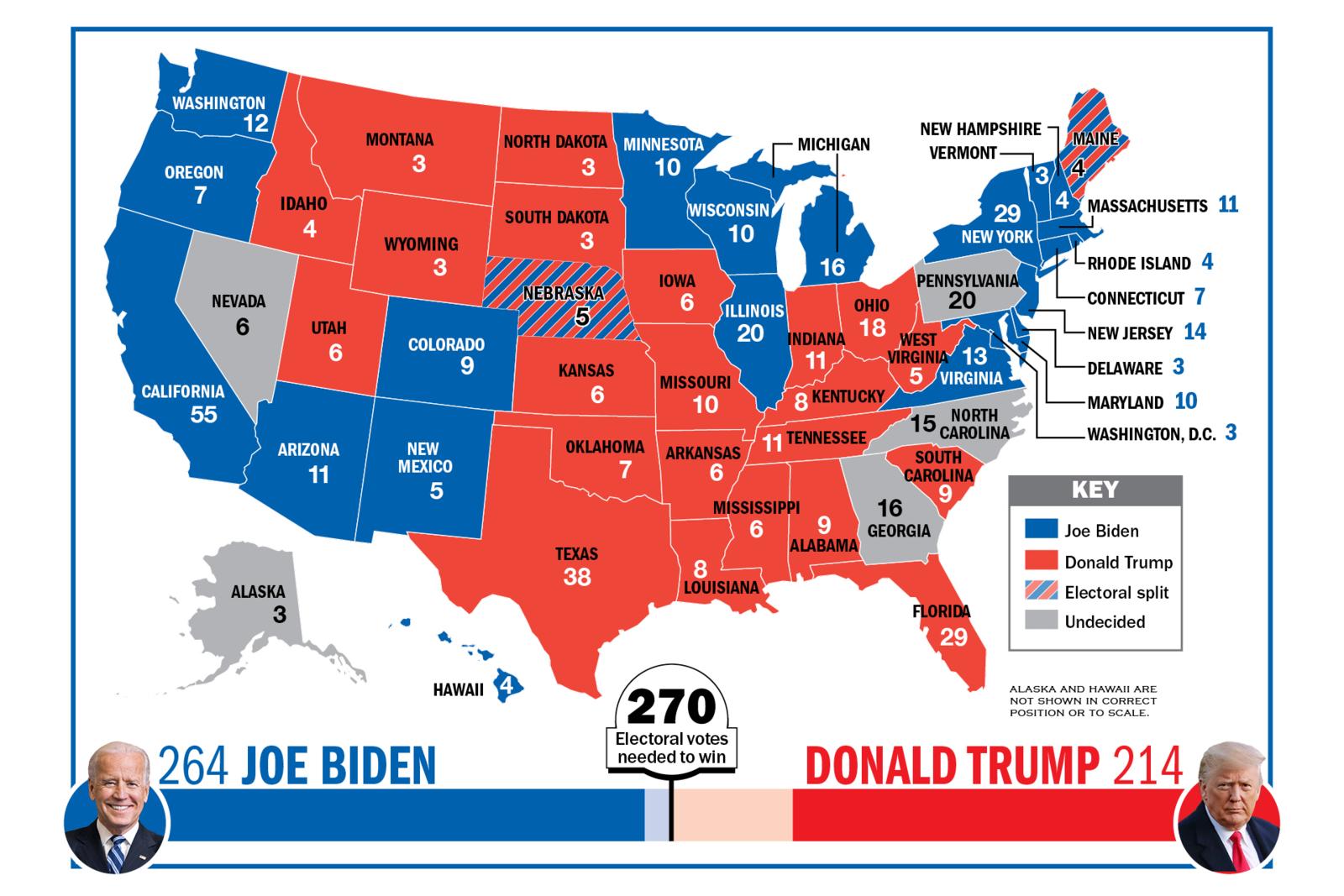

In 2016, Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by nearly 2.9 million ballots. By that metric, she was "winning the vote" nationally. But as we know, the geography of those votes meant she didn't win the presidency. This creates a massive psychological rift for voters. You see your candidate ahead in the national headlines, but they’re actually underwater in the three counties in Pennsylvania or Wisconsin that actually decide the outcome. It’s frustrating. It’s confusing. And it makes people feel like the system is broken.

Why the Polls Might Be Lying to You (Accidentally)

It isn't a conspiracy. It’s math, and math is getting harder.

Back in the day, pollsters called landlines. People answered their phones. Today? Nobody answers a call from an unknown number. If they do, it’s usually someone with a very specific personality type—someone who wants to talk about politics. This creates "non-response bias." If one side’s supporters are more excited or more prone to talking to strangers, the data skews.

💡 You might also like: JD Vance River Raised Controversy: What Really Happened in Ohio

Look at the 2020 election. The polls suggested a "Blue Wave" that never quite materialized to the extent predicted. Joe Biden won, but the margins in the House and in key swing states were razor-thin. Pollsters like Ann Selzer, who is legendary for her accuracy in Iowa, have pointed out that capturing the "quiet voter"—the person who doesn't post on X (formerly Twitter) or put a sign in their yard—is the hardest part of the job.

The Swing State Grind

If you want to know who’s winning the vote today, ignore the national numbers. They’re basically vanity metrics. You have to look at the "Blue Wall" (Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin) and the Sun Belt (Arizona, Nevada, Georgia, North Carolina).

In these states, the "winner" often changes based on which demographic shows up.

- Urban Turnout: Can the Democrats get enough votes in Philadelphia or Atlanta to offset the rural areas?

- Rural Surge: Can Republicans drive up margins in places where the population is sparse but the loyalty is fierce?

- The "Double Haters": This is a real term used by analysts like Amy Walter of the Cook Political Report. These are voters who dislike both major candidates. Whoever they "dislike less" on Tuesday morning usually wins the vote.

Early Voting vs. Election Day

This is where it gets really messy. We now have "election season" rather than "election day."

Because of the massive shift toward mail-in ballots and early in-person voting, we often see a "Red Mirage" or a "Blue Shift." Republicans have traditionally preferred voting in person on the actual day. Democrats have leaned heavily into early voting.

So, on election night, it might look like one person is winning the vote by a landslide. Then, three days later, as the mail-in ballots from heavy urban centers are processed, the lead evaporates. It’s not fraud; it’s just the chronological order of how paper is touched by humans. Understanding this sequence is vital if you want to keep your sanity during a live broadcast.

📖 Related: Who's the Next Pope: Why Most Predictions Are Basically Guesswork

The Role of Third Parties and Spoilers

We can’t talk about who’s winning without mentioning the outliers. Whether it’s Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (before his exit/shifts), Jill Stein, or Cornel West, third-party candidates rarely win, but they decide who does.

In a race decided by 10,000 votes in a state like Wisconsin, a third-party candidate pulling 1% of the vote is the kingmaker. When people ask who is winning the vote, they often forget to subtract the people who are so fed up they’re choosing "none of the above" via a protest candidate. Historically, these voters break toward the challenger when the economy is bad and toward the incumbent when things feel stable.

The Money Trail

If you want a non-poll indicator of who’s winning, look at where the money is going. Not just the total raised, but the ad buy strategy.

Campaign managers like Jen O'Malley Dillon or Chris LaCivita don't spend millions of dollars in California or Texas if they don't have to. If you see a candidate suddenly dumping $5 million into a "safe" state like Virginia or Iowa, it’s a massive red flag. It means their internal polling—which is way more expensive and accurate than the public stuff—shows they are losing ground where they shouldn't be.

How to Actually Track the Winner

Stop looking at the top-line percentage. A "48% to 46%" lead is statistically meaningless if the margin of error is 3.5%. You’re looking at a tie.

Instead, look at:

👉 See also: Recent Obituaries in Charlottesville VA: What Most People Get Wrong

- Consumer Sentiment: People usually vote with their wallets. If the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index is trending up, the incumbent has a massive tailwind.

- Voter Registration Trends: Are more people registering as Independents? In many swing states, the "unaffiliated" block is now the largest group.

- Special Election Results: These are the best "canary in the coal mine." If a party is over-performing in a random local race in Ohio in the middle of March, they probably have a motivated base that will show up in November.

Actionable Steps for the Informed Citizen

It's easy to get swept up in the horse race. But being a "political junkie" isn't the same as being informed. If you want to cut through the noise and actually understand who is winning the vote as the cycle progresses, change your media diet.

First, check the methodology. If a poll only surveyed "likely voters," it might be missing a surge of first-time young voters. If it only surveyed "registered voters," it’s probably too broad. The "likely voter" screen is the gold standard for a reason.

Second, follow the "Nate Cohn" rule. Cohn, the chief political analyst for The New York Times, often emphasizes that the "undecideds" are where the movement happens. Don't look at the candidate's number; look at the "Other/Undecided" number. If it’s high (above 5-7%), expect a volatile finish.

Third, look at the ground game. Data doesn't knock on doors; people do. Reports on "canvassing efficiency" and "knock rates" are better indicators of a win than a flashy TV ad. A campaign that can't get its supporters to the polls is a campaign that loses, no matter what the polls say.

Finally, wait for the certification. In a digital world, we want instant results. But democracy is analog. It’s paper, ink, and signatures. The person "winning the vote" at 10:00 PM on Tuesday is often just the person whose precincts reported first. Real clarity takes time, and in a close race, that's exactly what we should expect.

To stay truly updated, focus on regional news outlets in the "big seven" swing states rather than national cable news. They are closer to the ground, they understand the local grievances, and they aren't trying to sell a national narrative. They’re just trying to count.