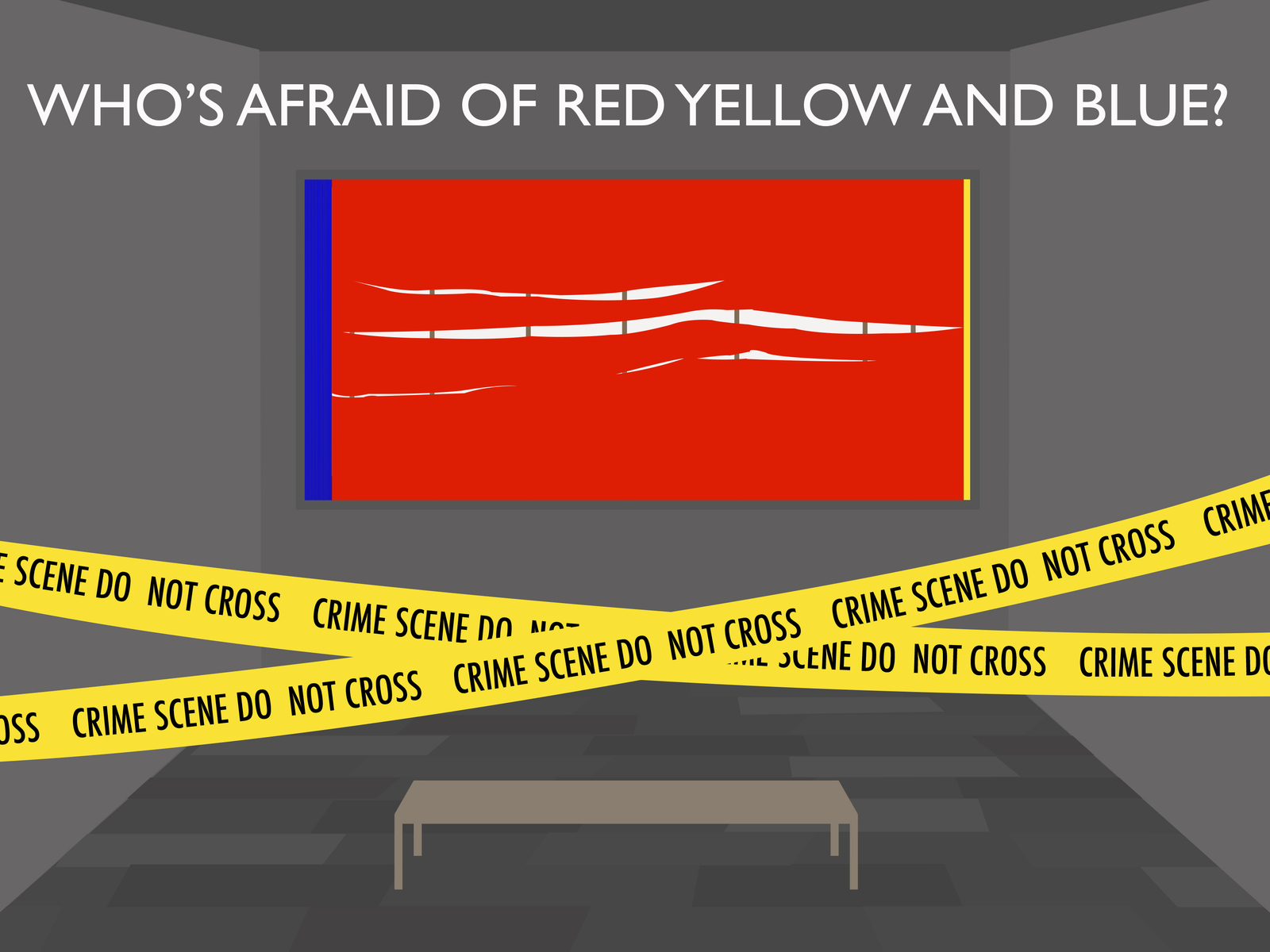

Barnett Newman didn't just paint big stripes. He invited chaos. When you stand in front of Who's Afraid of Red Yellow and Blue, you aren't just looking at primary colors. You’re looking at a series of paintings that literally drove people to violence. It’s weird, right? It is just paint on a canvas. Huge canvases, sure. But why did people feel the need to walk into a museum and physically attack these things with knives?

Honestly, the story of this series is one of the most stressful chapters in modern art history. Newman started the first one in 1966. He was part of the Abstract Expressionist crowd, guys who thought art could be a spiritual experience rather than just a picture of a bowl of fruit. He wanted to reclaim the primary colors from the strict, geometric grip of Piet Mondrian. Mondrian was all about grids and balance. Newman? He wanted scale. He wanted the color to swallow you whole.

Most people see "Who's Afraid of Red Yellow and Blue" and think, "My kid could do that." That’s the classic line. But they couldn't. Not at this scale. Not with this specific tension. The title itself is a play on "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" which was a hit play at the time. It’s a challenge. It’s Newman asking if we’re scared of the basic building blocks of light and vision. Turns out, some people were terrified. Or maybe they were just offended.

The Day the Canvas Bled

The most famous incident happened in 1986. A man named Gerard Jan van Bladeren walked into the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. He wasn't there to admire the brushwork on Who's Afraid of Red Yellow and Blue III. He pulled out a box cutter. He slashed the painting eight times. Long, jagged horizontal cuts.

Imagine being the museum director that day. It was a nightmare. But the drama didn't end with the stabbing. The restoration became an even bigger scandal than the attack itself. The museum hired an American restorer named Daniel Goldreyer. He claimed he could fix it. He charged hundreds of thousands of dollars.

But when the painting came back, people lost their minds. Critics said he didn't "restore" it; they said he "repainted" it with a roller. They claimed he used synthetic house paint instead of Newman’s original oil and egg tempera mix. The vibrant, breathing surface of the original was gone, replaced by a flat, plastic-looking slab of red. It was a second murder. Forensic labs were called in. Lawsuits were threatened. To this day, purists argue that the version of Who's Afraid of Red Yellow and Blue III you see now is a fake, a ghost of what Newman intended.

Why Does It Make People So Angry?

It’s just red. Mostly red. Two thin strips of yellow and blue on the edges.

Maybe that’s the problem. Who's Afraid of Red Yellow and Blue forces you to confront nothingness. When you stand close to it—the way Newman wanted you to—the red fills your entire peripheral vision. You lose your sense of space. For some, that’s meditative. For others, it’s a direct insult to their intelligence. There’s this specific type of rage that happens when someone feels like they’re being "tricked" by elite art circles.

👉 See also: How Old Was President Lincoln? The True Story of Honest Abe's Age and Why It Matters

Van Bladeren, the guy with the knife, eventually came back. Years later, he walked into another museum to attack Cathedra, another Newman piece. He clearly had deep-seated psychological issues, but he chose Newman as his target for a reason. These paintings are confrontational. They don't give you a place to rest your eyes. They demand that you feel something, even if that something is pure, unadulterated annoyance.

The Four Versions

Newman actually made four of these. Each one changed the proportions and the way the colors interacted.

- The first one is relatively small compared to the others.

- Number II is a vertical tower of color.

- Number III is the giant, the one that got slashed in Amsterdam. It’s over 17 feet wide.

- Number IV was the last, unfinished at the time of Newman's death in 1970.

Each iteration was a search for what Newman called "The Sublime." He wasn't trying to make something pretty for a living room wall. He was trying to create a "zip"—that’s what he called those vertical lines—that would act like a bolt of lightning, defining the space around it.

The Physics of Red

There’s actually some science behind why these colors mess with our heads. Red is a long-wavelength color. It physically appears closer to our eyes than blue does. When Newman puts a massive field of red next to a thin strip of blue, your brain's depth perception starts to get wonky. The painting starts to vibrate.

It’s not a static image. If you look at it long enough, the colors start to bleed into each other in your retinas. It’s an optical workout.

A lot of the hate comes from a misunderstanding of what a "painting" is supposed to do. If you think a painting is a window into a world, Newman's work is a failure. It’s not a window. It’s a wall. It’s an object that exists in the room with you. It’s heavy. It’s loud. It’s "Who's Afraid of Red Yellow and Blue" because it dares you to accept it as it is, without a story or a landscape to hide behind.

The Ghost of Mondrian

You can't talk about these works without talking about Piet Mondrian. You know his stuff—the black grids with the little squares of primary colors. Mondrian was the king of "De Stijl." He wanted everything to be perfectly balanced and mathematical.

🔗 Read more: The Sensory Deprivation Tank Charlotte Scene: What Actually Happens When You Go Under

Newman thought that was boring. He thought it was too "designed." He wanted to blow the lid off Mondrian's cage. By making the red so dominant that it almost pushes the yellow and blue off the canvas, Newman was basically declaring war on the idea of "balance." He wanted "oneness."

It was a radical move for the 1960s. At the time, the art world was shifting. Pop Art was coming in with its soup cans and comic books. Minimalists were making cold, industrial boxes. Newman was the bridge. He was a guy who used the language of minimalism but kept the soul and the "big feelings" of the older generation.

How to Actually Look at a Newman

Next time you're in a museum and you see Who's Afraid of Red Yellow and Blue (or any Newman piece), don't just walk past it. And please, don't say the kid thing.

Try this:

- Get close. Not "touching" close—security will tackle you—but close enough that the painting fills your vision.

- Stop looking for "things." You aren't going to find a hidden face or a secret message.

- Notice the edges. See how the paint meets the "zip"? Is it a sharp line, or does it bleed a little?

- Feel the scale. Notice how the red feels "heavy" or "hot."

There’s a reason these paintings are worth tens of millions of dollars. It’s not just because they’re old or because some rich guy said so. It’s because they represent a moment in human history where we tried to see how much we could take away from art and still have it feel like a punch in the gut.

The Legacy of the Slash

The vandalism of the third painting actually became part of its history. In a weird, dark way, Van Bladeren's knife made the painting more famous than it ever would have been on its own. It highlighted the vulnerability of art. It showed that even a simple field of color can be so provocative that it triggers a "fight or flight" response.

The restoration controversy also taught the art world a massive lesson about "integrity." It changed how museums handle modern materials. We realized that you can't just fix a Newman with a hardware store roller. The texture matters. The hand of the artist matters. Even if that "hand" just looks like a flat red wall to the untrained eye, there is a specific DNA in those brushstrokes that can't be faked.

Actionable Ways to Appreciate Color Field Art

If you want to dive deeper into this world without getting a headache, start small. You don't have to love Newman immediately.

- Visit a Rothko Room: Mark Rothko is Newman's cousin in spirit. His rooms (like the Rothko Chapel in Houston) are designed for silence. It helps you understand the "vibe" Newman was going for.

- Study Color Theory: Look into the "Afterimage" effect. Stare at a bright red square for 30 seconds, then look at a white wall. You’ll see green. This is exactly the kind of biological trickery Newman was playing with.

- Read "The Sublime is Now": This is Newman's 1948 essay. It’s dense, but it explains his philosophy. He didn't want to make "beauty." He wanted to make "truth."

- Compare the Four Versions: Look up high-resolution images of the whole series. Notice how the mood changes when the blue is a thick bar versus a tiny sliver. It’s like changing the volume on a stereo.

Who's Afraid of Red Yellow and Blue remains a litmus test. If you look at it and feel nothing, that’s fine. If you look at it and feel angry, Newman actually succeeded. He wanted to provoke. He wanted to move you. He just probably didn't want you to bring a box cutter.

The real power of the work isn't in the paint itself, but in the space between the canvas and your eyes. It’s a mirror. If you see a boring red wall, maybe you aren't looking hard enough. If you see a terrifying abyss, you’re right on track. The primary colors are the most basic things we have, and yet, as Newman proved, they are enough to start a riot.

When you strip away the figures, the stories, and the fluff, you're left with the raw materials of existence. Red. Yellow. Blue. And the question remains: are you afraid of them?

Next Steps for Art Enthusiasts

To truly grasp the impact of Newman's work, your next step should be to visit a major modern art collection—such as the MoMA in New York or the Tate Modern in London—and spend at least ten minutes sitting in front of a single large-scale color field painting. Avoid the temptation to check your phone or read the wall plaque immediately. Simply observe how the color affects your physical sense of space and whether the "vibration" Newman described occurs for you. This experiential approach is the only way to move past the "my kid could do that" mental block and understand why these works continue to dominate the narrative of 20th-century art.