You’ve heard it in elementary school assemblies. You’ve heard it at campaign rallies. Heck, you’ve probably hummed it while sitting in traffic. Most people think it’s just a sunny, patriotic alternative to the National Anthem—a musical postcard of the United States. But when you ask who wrote This Land Is Your Land song, you aren't just looking for a name. You're looking for Woody Guthrie, a man who was actually pretty annoyed when he sat down to write it in a drafty New York City hotel room in 1940.

Guthrie didn't write it because he was feeling particularly "God Bless America" that day. In fact, it was the exact opposite. He was sick of hearing Kate Smith’s version of "God Bless America" on the radio every five minutes. To Woody, that song felt out of touch with the bread lines and the dust-bowl reality he saw every day. He originally titled his response "God Blessed America for Me," which sounded a lot more sarcastic than the version we sing today.

The man behind the dust

Woody Guthrie was a rambler. Born in Okemah, Oklahoma, in 1912, he lived through the kind of stuff that would break most people. He saw his family's fortune vanish, his sister die in a fire, and his mother succumb to Huntington’s disease. By the time he was hopping freight trains toward California, he had a guitar strapped to his back and a head full of socialist ideals. He wasn't some polished Nashville star. He was a guy who wrote songs on napkins and cigarette packs.

Woody was a prolific writer, but he was also a bit of a musical thief. That’s not a dig—it's just how folk music worked back then. The melody for "This Land Is Your Land" wasn't something he dreamed up out of thin air. He lifted it almost directly from a Baptist gospel hymn called "When Our Lord Shall Come Again," specifically a version recorded by the Carter Family known as "Little Darling, Pal of Mine." If you listen to the Carter Family track, the resemblance is uncanny. It’s the same bouncy, rhythmic stroll.

Why the song was almost a protest anthem

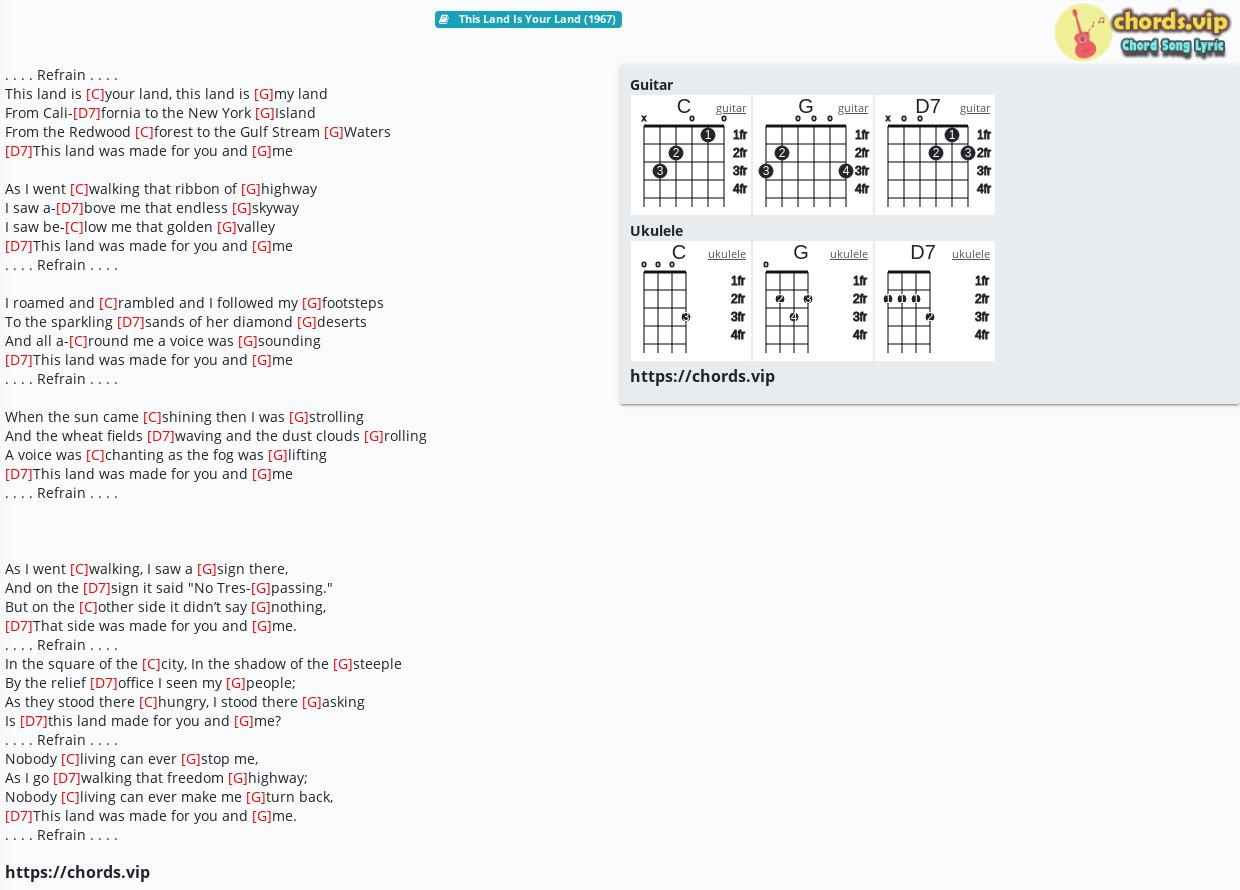

When people ask who wrote This Land Is Your Land song, they usually imagine a guy smiling at a redwood tree. But Guthrie’s original 1940 manuscript included verses that would make a modern school board sweat. There’s one verse about a "big high wall" that tried to stop him, with a sign that said "Private Property." On the back side of that sign, it said nothing—and Woody sang, "That side was made for you and me."

💡 You might also like: Dark Reign Fantastic Four: Why This Weirdly Political Comic Still Holds Up

Then there’s the "Hunger" verse. He wrote about people standing in the shadow of a steeple by the relief office, wondering if "God Blessed America" for them, too.

Most of these gritty details got sanded off over the decades. By the time the song became a staple of the American songbook in the 1950s and 60s, it had been cleaned up for the masses. Pete Seeger, a close friend of Woody’s, did a lot to keep those radical verses alive, but the radio-friendly version usually sticks to the sparkling sands and the diamond deserts. It’s funny how a song meant to challenge the idea of private property became a jingle used to sell everything from cars to insurance.

The timeline of a masterpiece

- February 23, 1940: Woody writes the lyrics at the Hanover House hotel in NYC.

- 1944: He finally records it for Moses Asch at Folkways Records.

- 1945: Guthrie publishes a mimeographed booklet of his songs, including this one, but the lyrics change slightly.

- 1951: The song is published in a more formal songbook, and the "Private Property" and "Relief Office" verses are notably absent.

The complicated legacy of Woody Guthrie

Woody wasn't just a folk singer; he was a political lightning rod. He wrote a column for the Daily Worker. He had "This Machine Kills Fascists" scrawled across his guitar. Because of this, the song faced some pushback during the Red Scare. People were suspicious of the guy who wrote This Land Is Your Land song because his views didn't exactly align with the McCarthy-era status quo.

But you can't kill a good tune.

📖 Related: Cuatro estaciones en la Habana: Why this Noir Masterpiece is Still the Best Way to See Cuba

By the time Woody died in 1967 from Huntington's disease, the song had already escaped his control. It belonged to the people, just like he said it did. It’s been covered by everyone: Bruce Springsteen, Aretha Franklin, Lady Gaga, and even Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings. Each artist brings their own flavor to it. Springsteen plays it like a gritty survivalist anthem. The Weavers played it like a campfire singalong.

What most people get wrong

The biggest misconception is that the song is purely celebratory. If you only sing the first three verses, sure, it’s a travelogue. But if you ignore the context of 1940—a country still reeling from the Great Depression and on the brink of World War II—you miss the point. Woody was asking a question: Who does this country actually belong to? Is it the people working the land, or the people with the "Private Property" signs?

Honestly, the song is kind of a Rorschach test. If you’re a patriot, you hear a love letter to the American landscape. If you’re an activist, you hear a demand for equity. Woody probably liked it that way. He wasn't a fan of "soft songs" that make you feel like you're just born to lose. He wanted songs that built you up and made you feel like you had a stake in the world.

Real-world impact and controversy

In recent years, the song has come under fire for what it doesn't say. Indigenous activists have pointed out that "This land is your land" ignores the fact that the land was stolen from Native American tribes long before Woody hopped his first train. It’s a valid critique. While Woody was writing from the perspective of a displaced white laborer in the 1930s, the "your land" part of the lyric carries a different weight depending on who is singing it.

👉 See also: Cry Havoc: Why Jack Carr Just Changed the Reece-verse Forever

Even with those complexities, the song remains a foundational piece of American culture. It’s been preserved in the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress. It’s not just a song; it’s a primary source document for the American experience.

How to explore the song further

If you want to really understand the man who wrote This Land Is Your Land song, you can't just stick to the Spotify hits. You have to go deeper.

- Visit the Woody Guthrie Center: Located in Tulsa, Oklahoma, it holds the original handwritten lyrics. Seeing the scribbles and the crossed-out lines on that yellowed paper makes the history feel real.

- Listen to the Library of Congress Recordings: Alan Lomax interviewed Woody in 1940. It’s hours of Woody talking, singing, and telling tall tales. It’s the closest you’ll get to sitting in a room with him.

- Read "Bound for Glory": Woody’s semi-autobiographical novel. It’s a bit exaggerated—Woody was a storyteller, after all—but it captures the "vibe" of the era perfectly.

- Check out the "Lost" verses: Find a recording by Pete Seeger or Arlo Guthrie (Woody’s son) where they include the verses about the "No Trespassing" signs. It changes the entire meaning of the song.

Woody Guthrie lived a hard, messy, beautiful life. He didn't write a "perfect" song, and he didn't write it for the money (he famously said "all you can write is what you see"). He wrote it for the people he met in hobo jungles and migrant camps. So next time you hear those opening chords, remember the guy in the NYC hotel room with the dusty guitar. He wasn't trying to give us a National Anthem; he was trying to give us a voice.

To truly grasp the weight of this anthem, listen to the 1944 Folkways recording first, then compare it to the modern interpretations. Pay attention to which verses are included and which are left out. You’ll start to see a map of American history hidden in those simple chords. Dig into the Smithsonian Folkways archives to hear Woody's raw, unpolished voice—it’s the best way to honor the intent of the man who gave us these lyrics.