Alexander Graham Bell. That’s the name we all learned in third grade, right? If you’re playing trivia at a bar and the question "who was the inventor of the telephone" pops up, you’re betting the house on Bell. Honestly, you’d probably win the point. But history is messy. It’s a tangle of patent lawsuits, late-night workshop breakthroughs, and guys dying in poverty while others became billionaires.

The story isn't just about one dude with a beard shouting for his assistant to come here because he wanted him. It's actually a wild race. You have a Scottish immigrant in Boston, an Italian genius in Staten Island, and a professional inventor from Chicago all trying to turn electricity into human speech at the exact same time.

The Patent Office Drama of 1876

On February 14, 1876, something happened that still keeps historians arguing over their coffee. Alexander Graham Bell’s lawyer filed a patent application for the telephone. Just a few hours later—literally the same day—a guy named Elisha Gray filed a "caveat," which is basically a placeholder for a patent, for the very same invention.

It was a photo finish.

Because Bell’s paperwork got there first, he’s the one we see on the stamps. But was he actually first? Some people think Bell’s lawyers got a sneak peek at Gray’s ideas and added a handwritten note to Bell’s application at the last minute. This isn't just some conspiracy theory; there’s a famous diagram of a liquid transmitter in Gray’s caveat that looks suspiciously like a sketch in Bell’s notebook from a few days later.

Bell was a teacher of the deaf. He understood sound better than almost anyone. His father and grandfather were both experts in elocution. You could say sound was the family business. He wasn't just trying to make a phone; he was trying to figure out how to help people communicate. That’s a huge distinction. While others saw a business opportunity, Bell saw a biological challenge. He spent years studying how the human ear works, even using a real human ear from a cadaver to see how the tiny bones vibrated. It sounds creepy, but it worked.

Antonio Meucci and the Staten Island Connection

Long before Bell or Gray even stepped into a patent office, an Italian immigrant named Antonio Meucci was already talking through wires. This was back in the 1850s. Meucci was a set designer and a tinkerer who lived in Staten Island. He developed a "telettrofono" to connect his basement laboratory to his wife’s bedroom because she had chronic arthritis and couldn't move well.

Meucci was brilliant, but he was broke.

👉 See also: How to Log Off Gmail: The Simple Fixes for Your Privacy Panic

He didn't have the $250 needed to file a permanent patent. He filed a temporary one in 1871, but he couldn't afford to renew it three years later. When Bell’s patent was granted in 1876, Meucci tried to sue. He claimed he had sent his prototypes to the Western Union Telegraph Company, the same company Bell was working with, and they "lost" them.

Imagine being Meucci. You’ve invented the future, but because you can't pay your bills, someone else gets the credit. In 2002, the U.S. House of Representatives actually passed a resolution (H.Res. 269) acknowledging Meucci’s work and essentially saying that if he’d been able to pay that patent fee, Bell might not have been the official inventor.

It’s a heartbreaker.

How the Tech Actually Worked

In the early days, telephones didn't have dials or buttons. You didn't even have a ringer. If you wanted to call someone, you just picked up the thing and started shouting into it, hoping the person on the other end was listening. It was basically a glorified intercom.

Bell’s big breakthrough was "undulating current." Before him, people thought you had to turn the electricity on and off rapidly—like Morse code—to send sound. Bell realized you needed a continuous, varying current that mimicked the shape of a sound wave.

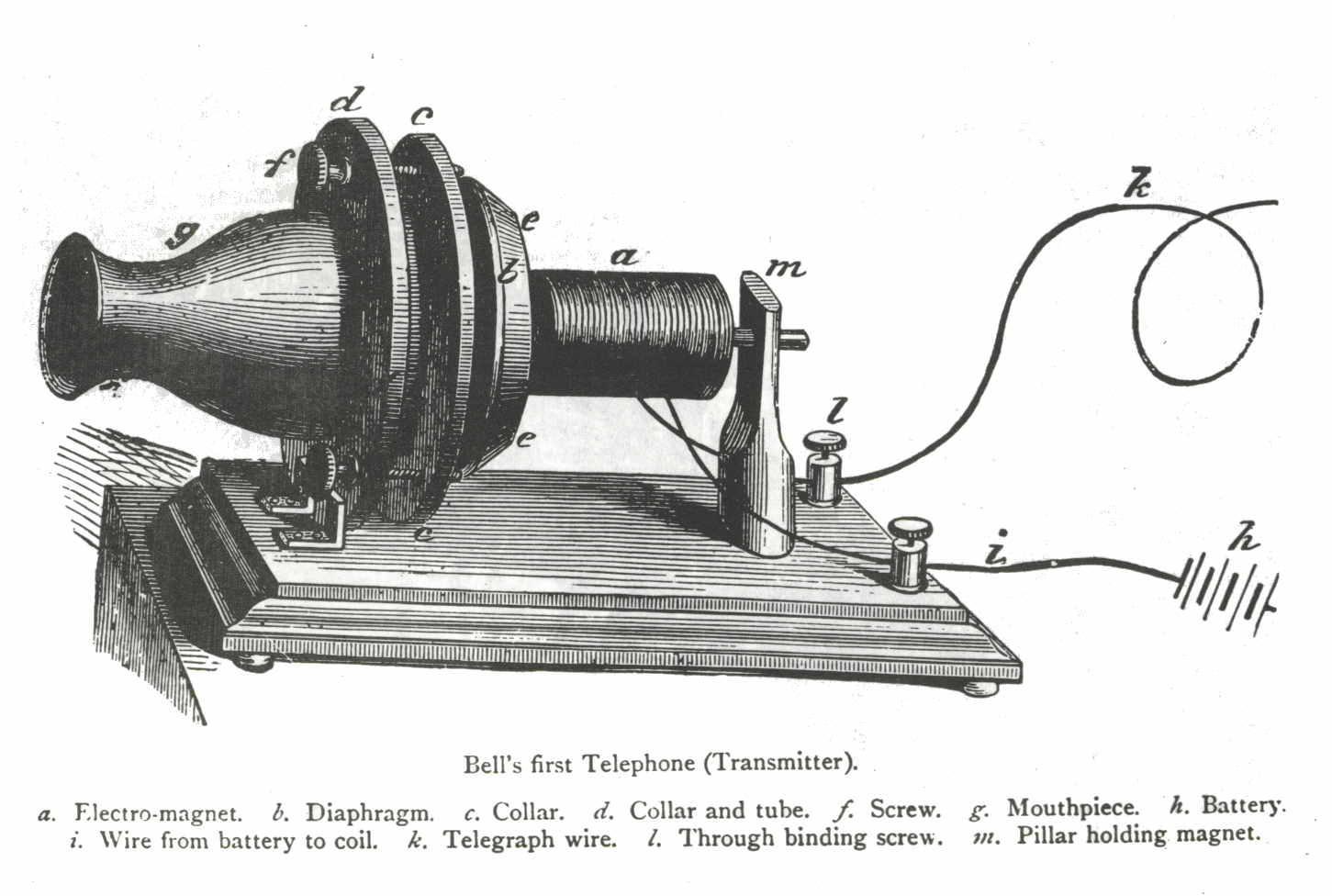

- The Transmitter: This was the "mouthpiece." You spoke into a diaphragm that vibrated a needle in a cup of water and acid (in the early liquid version) or against a magnet.

- The Wire: This carried that fluctuating electrical signal over a distance.

- The Receiver: On the other end, the electricity moved another diaphragm, which pushed the air and recreated the sound of your voice.

It was primitive. It was scratchy. It barely worked. But it was a miracle.

Why Bell Won the Long Game

If so many people were working on this, why is Bell the household name? It comes down to the Bell Telephone Company. Bell wasn't just an inventor; he was backed by powerful financiers like Gardiner Greene Hubbard (who also happened to be his father-in-law). They built an empire.

✨ Don't miss: Calculating Age From DOB: Why Your Math Is Probably Wrong

They sued everyone. Seriously, everyone.

The Bell Company fought over 600 lawsuits in eighteen years. They won every single one of them. They were the original "Big Tech." By the time the patents expired, the Bell System had already laid the wires and built the switchboards. They had the infrastructure. In the world of technology, being first is great, but being the one who builds the network is how you stay on top.

Johann Philipp Reis: The German Contender

We can't talk about who was the inventor of the telephone without mentioning Johann Philipp Reis. Around 1860, this German teacher built a machine he called the "Telephon." It could transmit musical notes and even a few muffled words.

"The horse does not eat cucumber salad."

That was allegedly one of the first phrases sent over his wire. Why that? Probably because it’s a weird enough sentence that you’d know for sure if you heard it correctly. Reis’s device was "make-and-break," meaning it cut the current on and off. This worked okay for music but was terrible for speech. Because his device wasn't commercially viable for conversation, he usually gets relegated to the footnotes of history. But he gave us the name. He called it a telephone before Bell even had his first beard trim.

The Human Side of the Invention

Bell’s wife, Mabel Hubbard, was deaf. So was his mother. This is the part of the story that feels most human to me. Bell spent his life trying to bridge the gap between the world of sound and the world of silence. He didn't even want a telephone in his own study eventually because he found it a distraction from his deeper scientific work.

He moved on to inventing hydrofoils and metal detectors. He even tried to make a "photophone" that sent sound on a beam of light—basically the ancestor of fiber optics. The man was restless.

🔗 Read more: Installing a Push Button Start Kit: What You Need to Know Before Tearing Your Dash Apart

Sorting Through the Claims

So, who was the inventor of the telephone? If you look at it strictly through the lens of the law, it’s Bell. He had the patent. He had the working model. He had the supreme court rulings.

If you look at it through the lens of pure innovation, it’s a tie between Meucci, Gray, and Bell, with a nod to Reis for the groundwork.

Honestly, inventions like this rarely happen in a vacuum. It’s like popcorn. The heat (the scientific understanding of electromagnetism) gets turned up, and eventually, kernels start popping all over the place. Bell just happened to be the one who caught the biggest piece in his bucket.

Actionable Steps for History Buffs and Techies

If this messy history fascinates you, don't just take my word for it. There are ways to see this history for yourself and understand how these early devices paved the way for the iPhone in your pocket.

- Visit the Smithsonian: The National Museum of American History in D.C. has Bell’s early experimental models, including the famous large-box telephone. Seeing how bulky and "steampunk" they look in person changes your perspective on the tech.

- Read the Court Cases: If you really want to go down the rabbit hole, look up The Telephone Cases (126 U.S. 1). It’s a massive legal document from 1888 where the Supreme Court tried to settle the "who did it first" debate once and for all. It’s surprisingly readable and full of drama.

- Test the Physics: You can actually build a basic "string phone" or a simple electromagnetic receiver with some copper wire and a magnet. It’s a great way to understand the "undulating current" concept that gave Bell the edge over the "make-and-break" guys.

- Explore Local History: If you’re ever in Staten Island, check out the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum. It’s the house where Meucci lived while he was developing his prototypes. It puts a face and a home to the guy history almost forgot.

- Analyze Patent Filings: Use Google Patents to look up Patent No. 174,465. This is the "Holy Grail" of telephony. Notice the language Bell uses—he doesn't even use the word "telephone" in the title; he calls it "Improvements in Telegraphy."

The telephone wasn't a "Eureka!" moment that happened in a single afternoon. It was a decades-long grind involving multiple geniuses, several of whom died without a penny to their name. Bell got the glory, but the telephone itself was the result of a collective human push to finally conquer distance.

Next time you hit "ignore" on a spam call, maybe give a little thought to Antonio Meucci or Elisha Gray. They fought like hell just for the right to say they were the ones who made that ringing possible.