If you’ve ever snapped your fingers to "My Girl" or felt that sudden surge of adrenaline when the bassline of "I Want You Back" kicks in, you’ve felt his influence. It’s unavoidable. But when people ask who was the founder of Motown Records, they usually just get a name: Berry Gordy Jr. That’s the short answer. The long answer involves an $800 loan, a failed jazz record store, and a gritty obsession with how cars were built on the Ford assembly lines in Detroit.

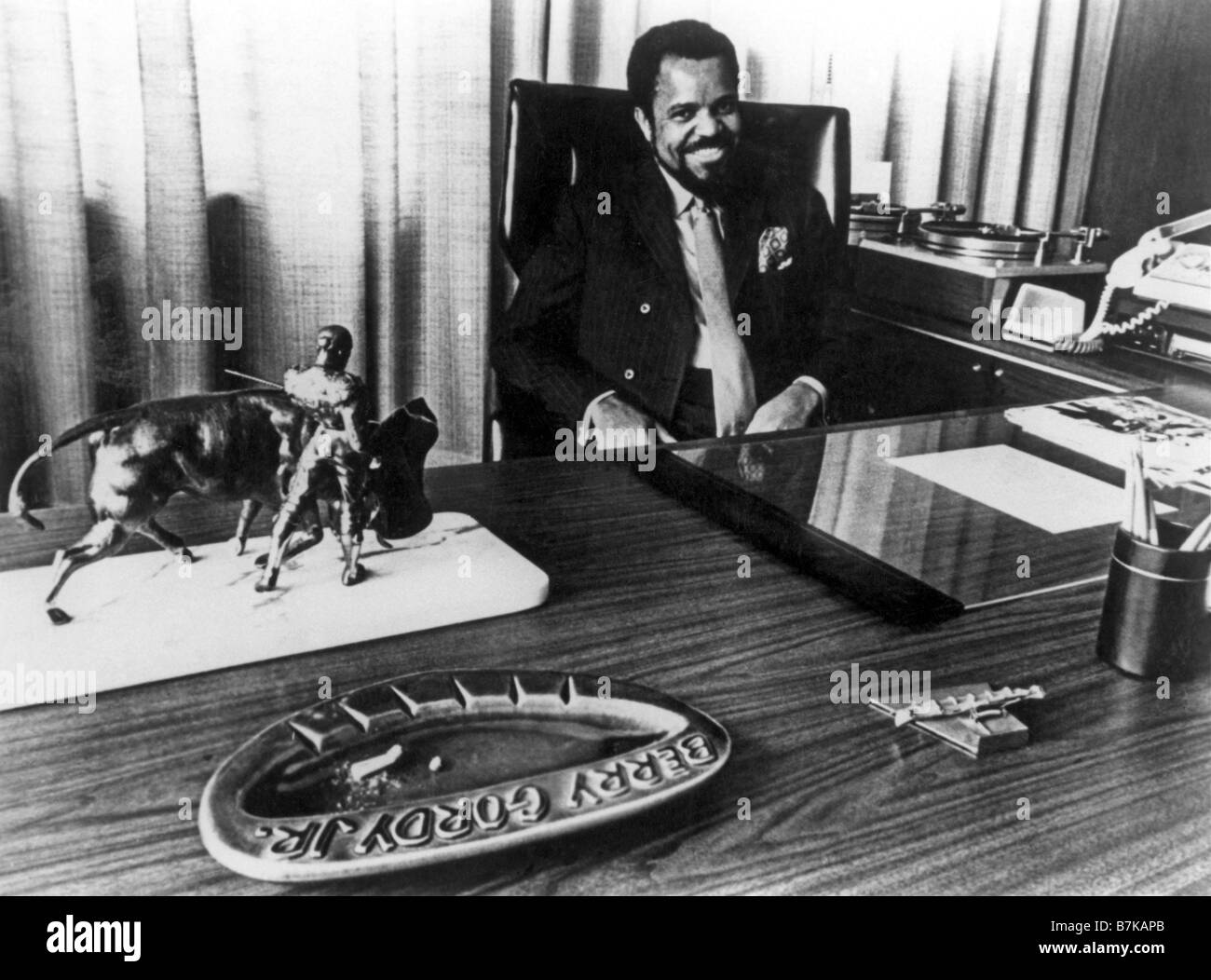

Berry Gordy didn’t just stumble into the music business. He was a professional boxer first. He fought fifteen Golden Gloves matches. You can see that fighter’s mentality in how he ran his label. He was tough. He was often polarizing. Honestly, some of his artists—the very ones he made famous—spent years suing him for better royalties. But without that specific man at that specific moment in 1959, the sound of young America would have stayed quiet.

The $800 Gamble That Changed Everything

Most people think Motown started with a massive investment. It didn't. In January 1959, Gordy borrowed exactly $800 from his family’s savings club, the Ber-Berry Co-operative. His family was tight-knit and entrepreneurial. They didn't just give him the money; they made him sign for it.

He bought a photography studio at 2648 West Grand Boulevard in Detroit. He renamed it "Hitsville U.S.A." It’s a bold name for a house that didn't have a single hit yet. But Gordy had a vision that was basically a carbon copy of the Lincoln-Mercury plant where he used to work. He saw how a raw chassis started at one end of the line and came out a shiny, finished car at the other. He thought, why not do that with singers?

He wasn't looking for finished products. He was looking for raw material. He took kids from the housing projects—kids like Diana Ross, Mary Wilson, and Florence Ballard—and put them through a literal "finishing school." He hired Maxine Powell to teach them how to walk, talk, and eat like royalty. He hired Cholly Atkins to choreograph their moves. He wanted them to be "acceptable" to white audiences during a time when Jim Crow laws were still very much alive. It was a calculated, brilliant, and sometimes ruthless strategy.

💡 You might also like: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

The Quality Control Meetings

You have to understand how obsessed this guy was with perfection. Every Friday morning, Motown held Quality Control meetings. Gordy would bring in the latest recordings and play them for the staff. Then he’d ask one question: "If you had only one dollar and you were hungry, would you buy this record or a sandwich?"

If the answer was "sandwich," the song went into the trash. Or it was sent back for a remix.

He pitted songwriters against each other. It was a pressure cooker. Smokey Robinson might bring in a track, but if Norman Whitfield had something better, Whitfield got the release. This internal competition is why Motown had a higher hit-to-release ratio than any other record company in history. It wasn't luck. It was an assembly line of geniuses.

The Secret Weapon: The Funk Brothers

While Gordy was the face and the founder, he knew he needed a backbone. That backbone was a group of jazz musicians he recruited from Detroit’s underground clubs. They were called the Funk Brothers. For years, the world didn't even know their names, yet they played on more number-one hits than the Beach Boys, the Rolling Stones, Elvis, and the Beatles combined.

📖 Related: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

Gordy kept them on a tight leash. He paid them well enough to keep them around but famously fined them if they played for other labels. It was a monopoly on talent. James Jamerson’s wandering bass lines and Benny Benjamin’s "snake" drumming became the "Motown Sound." If you listen to "Bernadette" by the Four Tops, you aren't just hearing a singer; you're hearing the absolute peak of Gordy's technical requirements for "high-end" frequency recording that would sound good on cheap transistor radios.

Success, Controversy, and the Move to L.A.

By the mid-60s, Motown was the most successful Black-owned business in the United States. Gordy was a kingmaker. He helped launch the careers of:

- Marvin Gaye (who was actually Gordy's brother-in-law for a while)

- Stevie Wonder (who Gordy signed when he was just eleven)

- The Supremes

- The Temptations

- Gladys Knight & the Pips

- The Jackson 5

But success brought friction. As the 1970s rolled around, the artists wanted more control. Marvin Gaye had to fight Gordy tooth and nail just to release What's Going On. Gordy hated the song at first. He called it "the worst thing I ever heard in my life" because it was too political. He was afraid it would ruin the brand. He was wrong. It became a masterpiece.

Then came the move to Los Angeles in 1972. Detroit felt betrayed. The "Hitsville" era was over, and the company shifted toward film and television. While the move made sense for Gordy's ambitions—like producing Lady Sings the Blues—it lost that gritty, basement-studio magic that defined the early years.

👉 See also: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

The Reality of the "Founder" Label

Berry Gordy eventually sold his interests in Motown. He sold the records division to MCA in 1988 for $61 million and later sold the publishing rights (Jobete) to EMI in stages for hundreds of millions more. He’s a billionaire now.

Is he a hero? To many, yes. He integrated the airwaves. He gave Black artists a platform that didn't exist before. Is he a villain? To some former artists who felt their contracts were predatory, maybe. But that’s the complexity of any great founder. He was a businessman first, an artist second, and a visionary always.

Actionable Insights for Music Lovers and Entrepreneurs

If you want to truly appreciate what Gordy built, stop listening to the "Best Of" playlists on Spotify for a second. Instead, do this:

- Listen to the mono mixes. Gordy specifically mixed Motown tracks for AM radio. The stereo mixes you often hear today actually lose the "punch" that Gordy was obsessed with.

- Watch the "Standing in the Shadows of Motown" documentary. It gives credit to the musicians Gordy kept in the background.

- Visit the Motown Museum in Detroit. Standing in Studio A (the "Snake Pit") is the only way to realize how tiny that room actually was. It’s a lesson in how physical constraints can actually breed massive creativity.

- Study the "Assembly Line" philosophy. If you're building a business, look at how Gordy standardized "quality" while allowing "talent" to shine. He proved that systems don't have to kill art; they can actually amplify it.

The story of Motown isn't just a story about music. It's a story about a guy who took the rhythm of a car factory and turned it into the heartbeat of a generation. Berry Gordy Jr. didn't just found a record label; he manufactured a culture.