Everyone knows the name. If you ask a random person on the street who was the first man to walk on the moon, they’ll give you the answer before you even finish the sentence. Neil Armstrong. It’s ingrained in our collective DNA at this point. But honestly, the way we talk about July 20, 1969, usually feels like a stale history textbook. We see the grainy black-and-white footage, hear the crackly "one small step" audio, and move on.

But it was terrifying.

People forget that the Eagle lander was basically a tin can running on less computing power than a modern toaster. Armstrong wasn’t just a passenger; he was a test pilot with a heart rate hitting 150 beats per minute as he realized the automated system was trying to dump them into a crater filled with boulders. He had to take manual control. He hovered. He searched. He landed with only about 25 seconds of fuel left in the tank. If he had hesitated for half a minute more, the mission would have ended in a crash or an emergency abort that might not have even worked.

That’s the reality of the situation. It wasn't a clean, clinical event. It was a gritty, high-stakes gamble that relied on the nerves of a guy who was known for being almost unnaturally calm under pressure.

Why Neil Armstrong was the one to step out first

There’s always been this bit of gossip about why Armstrong got the honors over Buzz Aldrin. In many earlier Gemini missions, the pilot—not the commander—was the one who did the spacewalks. So, naturally, a lot of people thought Aldrin would be the first one out the door. Buzz certainly thought so. He even lobbied for it a bit, which is understandable when you’re talking about the most significant milestone in human history.

But NASA had a different vibe in mind. They looked at the logistics and the personalities. First, the physical layout of the Lunar Module (LM) made it awkward. Armstrong was the commander, and he sat on the left. The hatch opened inward to the right. For Aldrin to get out first, he would have had to crawl over Armstrong in a pressurized suit while wearing a massive life-support backpack in a tiny cabin. It was a recipe for breaking something important.

More importantly, NASA leadership, specifically guys like Deke Slayton and George Mueller, wanted the first man on the lunar surface to be someone without a massive ego. They saw Armstrong as a quiet, "typical" American hero. He was an engineer’s engineer. He didn't want the fame; he just wanted to fly the machine. He was the quintessential professional.

💡 You might also like: Why the iPhone 7 Red iPhone 7 Special Edition Still Hits Different Today

The technical nightmare of the descent

We need to talk about the 1202 alarms. Imagine being 30,000 feet above a dead world, hauling a fragile craft toward the ground, and suddenly your computer starts screaming at you with "Executive Overflow" errors. That’s what happened. The computer was being overwhelmed with data it didn't need—specifically from the rendezvous radar which shouldn't have been on—and it was basically rebooting itself over and over.

Armstrong didn't panic.

He stayed focused on the window. While the world watched in silence, he was looking for a flat spot to park. The area the "auto-pilot" selected was a "boulder field" surrounding West Crater. Not ideal. He tilted the lander forward to gain horizontal speed, "hopping" over the hazard to find a clear patch of dirt.

When the "Contact Light" finally glowed on the dashboard, the world exhaled. But Armstrong and Aldrin didn't. They immediately went into a "stay/no-stay" checklist. They had to be ready to blast off instantly if the ground was unstable or if the fuel tanks started leaking. It was only after they confirmed they weren't about to explode or sink into the dust that they actually took a second to look out the window.

The "Small Step" and the missing word

"That's one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind."

The "a" is the most debated syllable in history. Armstrong always insisted he said it. In his mind, he had composed the sentence to include it, because without the "a," the sentence is technically a tautology—it basically says "one small step for mankind, one giant leap for mankind."

📖 Related: Lateral Area Formula Cylinder: Why You’re Probably Overcomplicating It

Linguistic analysts have spent decades poring over the audio tapes. In 2006, a computer programmer named Peter Shann Ford used high-tech sound analysis and claimed he found a 35-millisecond bump of energy that represented the missing "a." But other researchers aren't so sure. Honestly, it doesn't matter. The sentiment landed perfectly regardless of the grammar.

What’s really cool is what happened right after. Armstrong didn't just walk; he became a field geologist. He immediately scooped up a "contingency sample" of soil and tucked it into his suit pocket. If they had to leave suddenly, at least scientists would have something to study. He was thinking like a scientist even while standing in a place no human had ever seen.

What most people get wrong about the moon walk

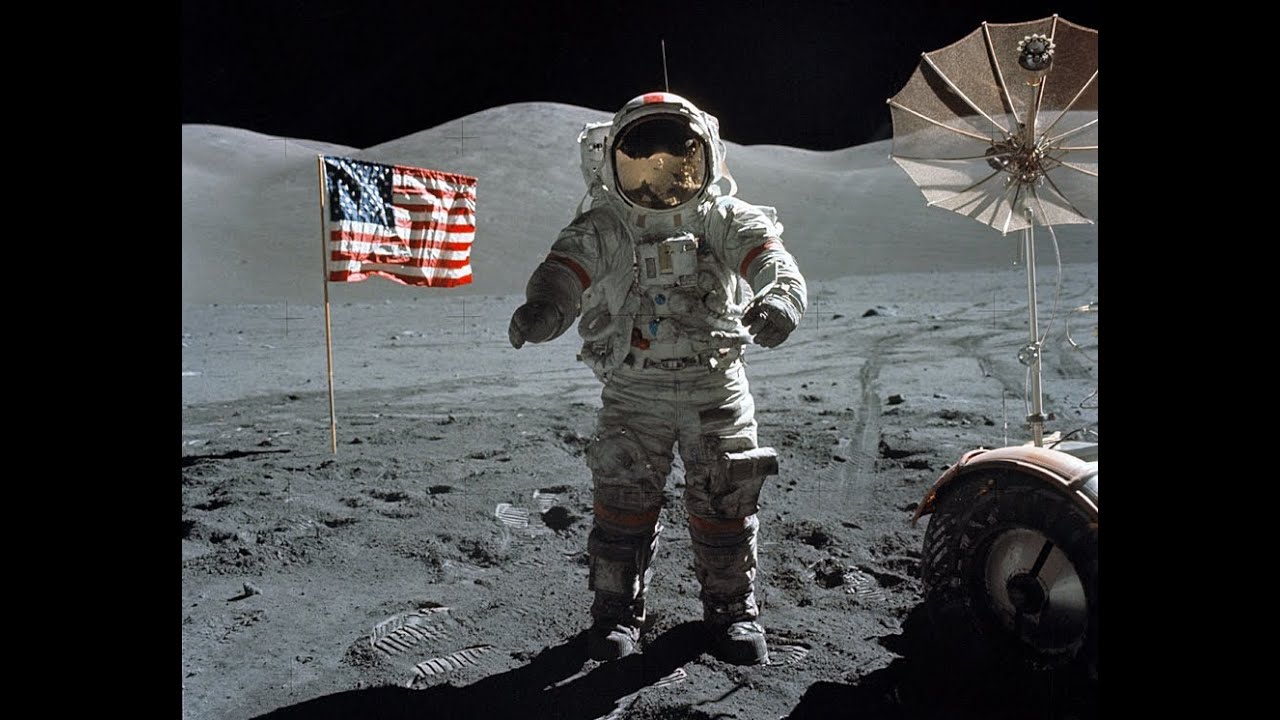

People think they spent the whole time jumping around like kids in a sandbox. In reality, the first moonwalk was incredibly scripted and physically demanding.

- The temperature was brutal. Even though it looks dark, they were in direct, unfiltered sunlight. The suits had to circulate chilled water to keep them from cooking.

- The dust was a nightmare. Lunar regolith is like crushed glass. It’s electrostatic, so it sticks to everything. It smelled like spent gunpowder, according to the astronauts once they got back inside and took their helmets off.

- They weren't out there that long. Armstrong and Aldrin were only on the surface outside the lander for about two and a half hours. Compare that to later missions like Apollo 17, where Harrison Schmitt and Gene Cernan spent over 22 hours exploring and driving a rover.

The primary goal of Apollo 11 wasn't science—it was proof of concept. They needed to show we could land, get out, and get back home without dying. Everything else was a bonus.

The lonely man in orbit

While we celebrate the man who walked on the moon first, we often ignore Michael Collins. He was the third man on the mission, staying behind in the Command Module, Columbia.

Collins was the loneliest human in history for those few hours. Every time his orbit took him behind the far side of the moon, he lost all radio contact with Earth and his friends on the surface. He was truly alone in the dark. He later wrote that he felt a sense of "awareness, anticipation, satisfaction, confidence, almost exultation," but also a profound weight of responsibility. If Armstrong and Aldrin couldn't get back off the surface, Collins would have had to return to Earth alone, a prospect that haunted him.

👉 See also: Why the Pen and Paper Emoji is Actually the Most Important Tool in Your Digital Toolbox

The legacy beyond the footprints

Neil Armstrong didn't go on to be a politician or a corporate shill. He taught engineering at the University of Cincinnati. He bought a farm. He stayed out of the limelight as much as he possibly could.

When he passed away in 2012, the world lost more than just a pilot. We lost the living link to the moment we stopped being a single-planet species. The footprints he left at Tranquility Base are likely still there, undisturbed by wind or rain, because the moon has no atmosphere. They’re a permanent record of a moment when the entire planet actually stopped and looked up at the same time.

How to explore this history yourself

If you're actually interested in the nitty-gritty of the Apollo missions, don't just watch the movies. Check out the Apollo Flight Journal. It’s a NASA-curated transcript of everything said on the loops, with expert commentary explaining the jargon.

You can also look up the "Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter" (LRO) images. This satellite is currently orbiting the moon and has taken photos so high-res that you can actually see the descent stage of the Eagle and the trails of footprints left by the astronauts. It’s the ultimate "receipt" for the moon landing skeptics.

Moving forward

To really grasp the scale of what happened, do these three things:

- Watch the "Apollo 11" documentary (2019): It uses 70mm footage that was discovered in the National Archives. There is no narrator. Just raw, restored footage and audio. It makes you feel the tension in the room.

- Read "First Man" by James R. Hansen: This is the only authorized biography of Armstrong. It goes deep into his psyche and why he was the way he was. It’s way more detailed than the Ryan Gosling movie.

- Download a Moon Map app: Find the Sea of Tranquility (Mare Tranquillitatis) next time there's a clear night. Knowing exactly where that little tin can landed makes the moon feel much less like a distant rock and more like a destination.

Armstrong may have been the first, but he always insisted he was just the tip of a spear involving 400,000 people who worked on the Apollo program. He was the one who got to put the boot down, but the achievement belonged to everyone.