You’ve probably heard the names Wilbur and Orville Wright since you were in kindergarten. It’s the standard answer in every history textbook across the United States. But if you hop on a plane and fly down to Brazil, you're going to hear a completely different story. Honestly, the question of who was the first inventor of the airplane isn't as simple as a single date or a couple of guys from Ohio. It’s a messy, high-stakes drama filled with steam engines, catapults, and some very public arguments about what "flying" actually means.

Most people think history is a straight line. It's not. It's a tangle. To understand who really got us off the ground, we have to look at the fine print of aviation history—the difference between a glider with a motor and a truly controllable machine.

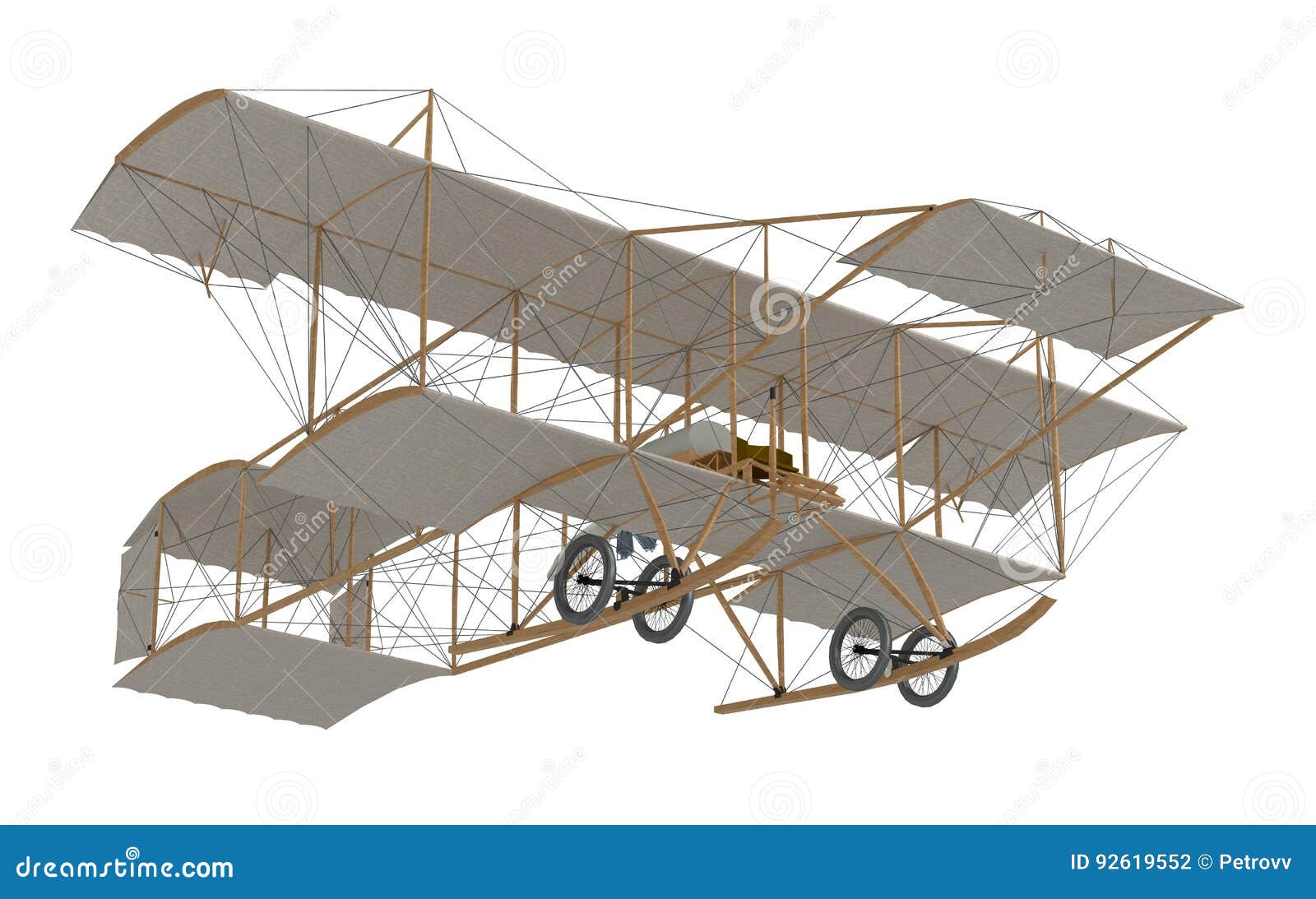

The Wright Brothers and the 12-second miracle

On December 17, 1903, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, the Wright brothers did something remarkable. Orville hopped into their "Flyer" and stayed in the air for 12 seconds. That's it. Just twelve seconds. It covered 120 feet, which is shorter than the wingspan of a modern Boeing 747.

But here is why they usually win the title of who was the first inventor of the airplane. They didn't just build a kite with an engine; they solved the "three-axis" problem. Basically, they figured out how to steer. Before the Wrights, people were just trying to get enough lift to stay up. The Wrights realized that if you can't turn, climb, or dive without crashing, you haven't really invented a plane—you've just built a very dangerous projectile. Their use of "wing warping" (literally twisting the wings to turn) was the secret sauce.

However, there’s a catch.

Hardly anyone saw them do it. They were secretive, bordering on paranoid. They didn't want people stealing their patents, so they did their early tests in a remote area and didn't perform public demonstrations for years. This secrecy created a massive vacuum that other inventors were happy to fill.

📖 Related: robinhood swe intern interview process: What Most People Get Wrong

The Brazilian Contender: Alberto Santos-Dumont

If you go to a bar in Rio de Janeiro and say the Wright brothers invented the plane, you might get kicked out. For Brazilians, the answer to who was the first inventor of the airplane is unequivocally Alberto Santos-Dumont.

In 1906, three years after Kitty Hawk, Santos-Dumont flew his 14-bis aircraft in Paris. Here’s the kicker: he did it in front of a huge crowd and a bunch of official witnesses. More importantly, his plane took off under its own power.

Wait. Why does that matter?

Well, the Wright brothers used a launch rail and, later, a catapult system to get their planes moving. Critics of the Wrights (and fans of Santos-Dumont) argue that if you need a catapult to get in the air, you aren't really "flying" in the way we think of it today. They see the Wright Flyer as a powered glider. Santos-Dumont’s plane had wheels and took off like a modern jet does—from a standstill on a flat field.

He was a bit of a rockstar, too. He wore high-collared shirts and Panama hats, and he famously commissioned Louis Cartier to make him a "wrist watch" because he couldn't check a pocket watch while holding the controls of his plane. He wanted flight to be for everyone, so he never patented his designs. He literally gave them away for free.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Looking for an AI Photo Editor Freedaily Download Right Now

The Smithsonian Scandal and the Great Aerodrome

There's a weird, dark chapter in this story involving the Smithsonian Institution. Before the Wrights, the Secretary of the Smithsonian, Samuel Langley, was working on his own machine called the "Aerodrome." He spent $50,000 of government money—a fortune back then—and it failed spectacularly, twice, crashing into the Potomac River.

For decades, the Smithsonian refused to acknowledge the Wright brothers as the first. Why? Because they wanted their former boss, Langley, to have the credit. They even displayed the Aerodrome with a sign saying it was the first "capable" of flight. It took a massive legal battle and Orville Wright threatening to send the original Flyer to a museum in London before the Smithsonian finally admitted the truth in the 1940s.

Other names you should probably know

We can't talk about who was the first inventor of the airplane without mentioning the people who did the "boring" math that made it possible.

- Sir George Cayley: Back in 1799, this English baronet figured out the four forces of flight: Lift, Weight, Thrust, and Drag. He’s basically the grandfather of aviation. He was the first to realize that wings should be curved (cambered) instead of flat.

- Otto Lilienthal: The "Glider King." This German engineer made thousands of flights in gliders he designed himself. He died when one of them stalled and crashed. The Wright brothers studied his data religiously. Without his tragic experiments, they never would have known how to shape their wings.

- Gustave Whitehead: This is the wildcard. Some residents of Connecticut swear that Whitehead, a German immigrant, flew a powered machine in 1901—two years before the Wrights. There's no photographic evidence, just newspaper accounts and affidavits. Most historians find it unlikely, but it's a persistent legend that keeps the debate spicy.

What counts as an "airplane" anyway?

The whole debate boils down to definitions. History is written by the people who meet the criteria set by the judges.

If you define "airplane" as a machine that:

✨ Don't miss: Premiere Pro Error Compiling Movie: Why It Happens and How to Actually Fix It

- Takes off under its own power...

- In front of witnesses...

- Using wheels...

Then the answer is Santos-Dumont.

If you define it as a machine that:

- Is heavier than air...

- Uses an internal combustion engine...

- Is fully controllable on three axes (pitch, roll, and yaw)...

Then the answer is the Wright Brothers.

Most of the scientific community sides with the Wrights because "control" is the hardest part of flight. Anyone can strap a motor to a wing and hope for the best. Making that wing go exactly where you want it to go? That’s engineering.

Why the Wrights eventually won the PR war

The Wrights weren't just inventors; they were relentless. After their 1903 flight, they spent the next two years at Huffman Prairie, a cow pasture near Dayton, Ohio. They flew in circles. They stayed up for 39 minutes. They made the plane practical.

When Wilbur finally went to France in 1908 to show off the plane, the European aviators were stunned. They had been building "planes" that could barely turn. Wilbur took off and performed figure-eights with effortless grace. One French aviator, Leon Bollee, famously said, "We are beaten! We don't exist!"

That moment in 1908 is what really cemented their legacy. It wasn't just about being first; it was about being the best.

Actionable insights for history buffs and aviation fans

If you want to dive deeper into the reality of early flight, stop looking at basic summaries and go to the primary sources. Here is how to actually verify the history:

- Visit the Library of Congress Digital Collections: You can read the Wright brothers' personal diaries and see their original sketches. It's fascinating to see how many times they failed before they succeeded.

- Check the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum: Now that the feud is over, they have the best technical breakdown of why the Wright Flyer worked while others didn't.

- Compare the flight logs: Look at the flight records of 1903 vs. 1906. You'll see that while Santos-Dumont was more public, the Wrights were achieving much longer flight times and much more complex maneuvers in private.

- Understand the "Three-Axis Control" concept: If you really want to understand the technology, look up how a modern Cessna turns. It uses the exact same principles (ailerons, elevator, rudder) that the Wrights perfected in 1903.

The story of the airplane isn't a "Eureka!" moment. It's a decade of trial, error, and guys jumping off sand dunes. Whether you credit the Wrights, Santos-Dumont, or the theorists like Cayley, the real winner was humanity, which finally managed to break its bond with the earth.