You’re probably sitting in front of one right now. Or maybe there's a glowing slab of glass in your pocket that does the exact same thing. We take the "boob tube" for granted, but the race to figure out how to hurl moving images through the air was a total mess. It wasn't just one guy in a lab. It was a decade-long brawl involving a farm boy from Utah, a Russian immigrant backed by a corporate giant, and a Scotsman working with old tea crates and sealing wax.

If you’re looking for a simple name to win a trivia night, you usually get Philo Farnsworth. But honestly, it’s more complicated than that.

The first inventor of television isn't a single person; it's a collection of geniuses who happened to be suing each other at the same time. You’ve got mechanical vs. electronic. You’ve got patents vs. prototypes. It’s a wild story about how a 14-year-old kid looked at rows of plowed hay and saw the future of global communication.

The Farm Boy and the Plowing Lines

Philo Farnsworth was basically a prodigy. While most kids in 1921 were worried about chores, Philo was obsessing over the limitations of mechanical disks. See, back then, people were trying to make TV happen using spinning wheels with holes in them. It was clunky. It was loud. It looked like garbage.

Philo was out in a potato field in Rigby, Idaho. He looked back at the parallel furrows he’d just plowed. It hit him. If you wanted to transmit a picture, you couldn't do it with a physical spinning disk. You had to scan an image line by line using electricity.

He called it the "Image Dissector."

He was only 14.

Think about that. Most of us were struggling with algebra, and this kid was mapping out the vacuum tube architecture that would eventually broadcast the moon landing. He didn't actually build it until 1927 in a lab in San Francisco. The first image he ever transmitted? A simple straight line. Later, when an investor asked when they’d see some "bucks" from the invention, Philo transmitted a dollar sign.

He had a sense of humor, at least.

The Scotsman and His Mechanical Nightmare

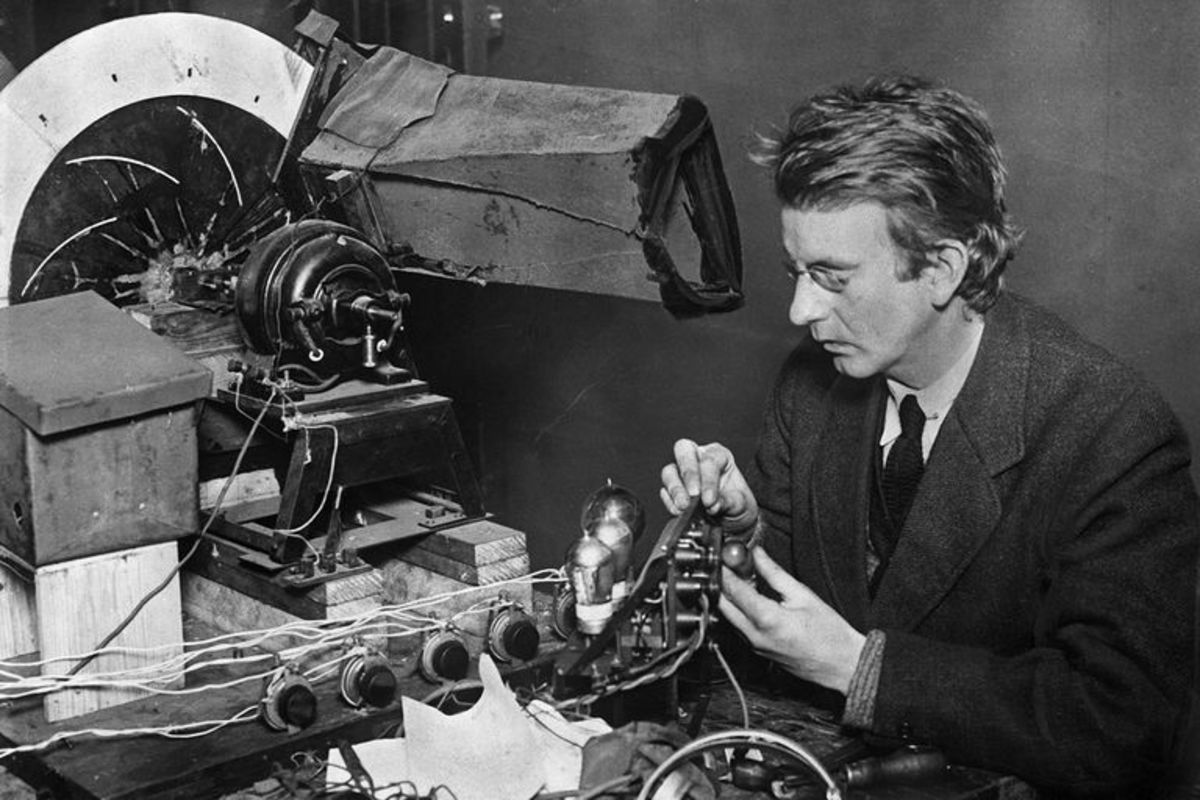

Before Philo got his electronic version working, a guy named John Logie Baird was making waves in London. If Philo is the father of electronic TV, Baird is the king of the mechanical version.

Baird’s setup was... well, it was sketchy.

💡 You might also like: Why It’s So Hard to Ban Female Hate Subs Once and for All

He used a washstand, a tea chest, biscuit tins, darning needles, and cardboard. He literally held his apparatus together with sealing wax and string. In 1925, he gave the first public demonstration of moving silhouette images. A year later, he showed off recognizable human faces at the Royal Institution.

But there was a problem.

Mechanical television had a ceiling. You can only spin a disk so fast before it flies apart. The resolution was terrible—we’re talking 30 lines of resolution. Your modern 4K TV has 2,160 lines. Baird’s images looked like flickering ghosts moving through a heavy fog.

Still, he was the first to get something moving on a screen. He even managed to transmit a signal from London to New York in 1928. It was a massive achievement, even if the technology was a dead end.

The Corporate Goliath: Vladimir Zworykin and RCA

Enter the villain of the story, or the hero, depending on who you ask at a cocktail party. Vladimir Zworykin was a Russian engineer working for Westinghouse and later RCA. He was brilliant. He also had the massive checkbook of David Sarnoff, the head of RCA, behind him.

Sarnoff wanted to own the airwaves.

In 1930, Zworykin visited Philo Farnsworth’s lab. Philo, being a nice guy who didn't understand corporate espionage, showed Zworykin everything. He explained how the Image Dissector worked.

Zworykin allegedly remarked, "This is a beautiful instrument. I wish I had invented it."

Then he went back to RCA and tried to do exactly that.

What followed was a brutal, multi-year patent war. RCA claimed Zworykin’s 1923 patent for an "Iconoscope" took priority. The problem? Zworykin couldn't actually get his version to work until after he saw Philo’s.

📖 Related: Finding the 24/7 apple support number: What You Need to Know Before Calling

The legal battle was ugly. It nearly broke Philo. But in a move that feels like a movie script, Philo’s old high school chemistry teacher, Justin Tolman, produced a sketch Philo had drawn on a chalkboard when he was 14. That drawing proved Philo had the idea first.

RCA lost. They had to pay Philo royalties. It was the first time in history RCA had to pay someone else for the right to use a patent they wanted.

Why Does This Matter Today?

We live in a world of "Content." But the first inventor of television wasn't thinking about Netflix or TikTok. They were thinking about light.

They were trying to solve the problem of how to take a three-dimensional world and flatten it into a stream of electrons.

The Evolution of the Screen

- 1920s: Mechanical disks (Baird) and the birth of the vacuum tube (Farnsworth).

- 1930s: The first high-definition broadcasts (which were only about 400 lines back then).

- 1940s: World War II stops TV production, but radar tech makes screens better later.

- 1950s: The "Golden Age." TV becomes a household staple.

- 1960s: Color finally takes over.

It's easy to forget how miraculous this was. Before this, if you wanted to see something, you had to be there. Or you had to wait for a photograph to be developed and mailed. TV made the world small.

The Tragic Ending of Philo Farnsworth

You’d think the guy who invented the most important device of the 20th century would be a household name like Edison or Bell.

He isn't.

Philo’s patents expired right as TV was finally taking off after World War II. He didn't make the billions RCA made. He spent much of his later life in relative obscurity, struggling with depression and alcohol. He even sort of hated what TV had become. He once said there was "nothing on it worthwhile" and didn't want his own kids watching it.

The irony is thick.

He did have one moment of redemption, though. In 1969, he sat in his living room and watched Neil Armstrong walk on the moon. He turned to his wife, Elma, and said, "This has made it all worthwhile."

👉 See also: The MOAB Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the Mother of All Bombs

The very tech he dreamt of in a potato field was now showing him another world.

Common Misconceptions About the Invention of TV

People often get hung up on the "first" part.

Was it Paul Nipkow? He invented the scanning disk in 1884. But he never built a working system. He just had the blueprints.

Was it Boris Rosing? He was Zworykin’s teacher and suggested using a cathode ray tube. But again, no working prototype.

The truth is, Philo Farnsworth was the first to build a completely electronic system that actually worked. No moving parts. No spinning wheels. Just pure electricity. That is why most historians give him the crown, even if the corporate machines tried to bury him.

How to Explore This History Yourself

If you’re a tech nerd or just a history buff, don't just take a Wikipedia summary for granted.

Real Steps to Dive Deeper:

- Visit the Franklin Institute: They house some of the original Farnsworth equipment. Seeing the scale of those early tubes is mind-blowing.

- Read "The Last Lone Inventor" by Evan I. Schwartz: This book is the definitive account of the fight between Farnsworth and Sarnoff. It reads like a legal thriller.

- Check out the National Museum of Scotland: They have a great collection of John Logie Baird’s early mechanical apparatus. It looks like something out of a steampunk movie.

- Look up the 1939 World's Fair: This was the moment RCA "introduced" TV to the public, conveniently downplaying Farnsworth's contributions.

The first inventor of television wasn't just a scientist. He was a visionary who saw lines in the dirt and turned them into light. Whether you're watching a prestige drama or a dumb cat video, you're looking at a legacy of lawsuits, grit, and a 14-year-old’s imagination.

TV didn't just happen. It was fought for.

Every time you hit the power button, you're seeing the result of a hundred-year-old war between the "lone inventor" and the corporate machine. And for once, the kid from the farm actually won the patent—even if the world forgot his name for a while.

Actionable Insight: Next time you’re troubleshooting your smart TV or complaining about the resolution, remember the "Image Dissector." If you want to support the legacy of independent invention, look into the Farnsworth Television & Radio Corporation archives or visit local tech museums that highlight "lost" inventors. Understanding who actually built our world changes how we value the tech in our pockets.