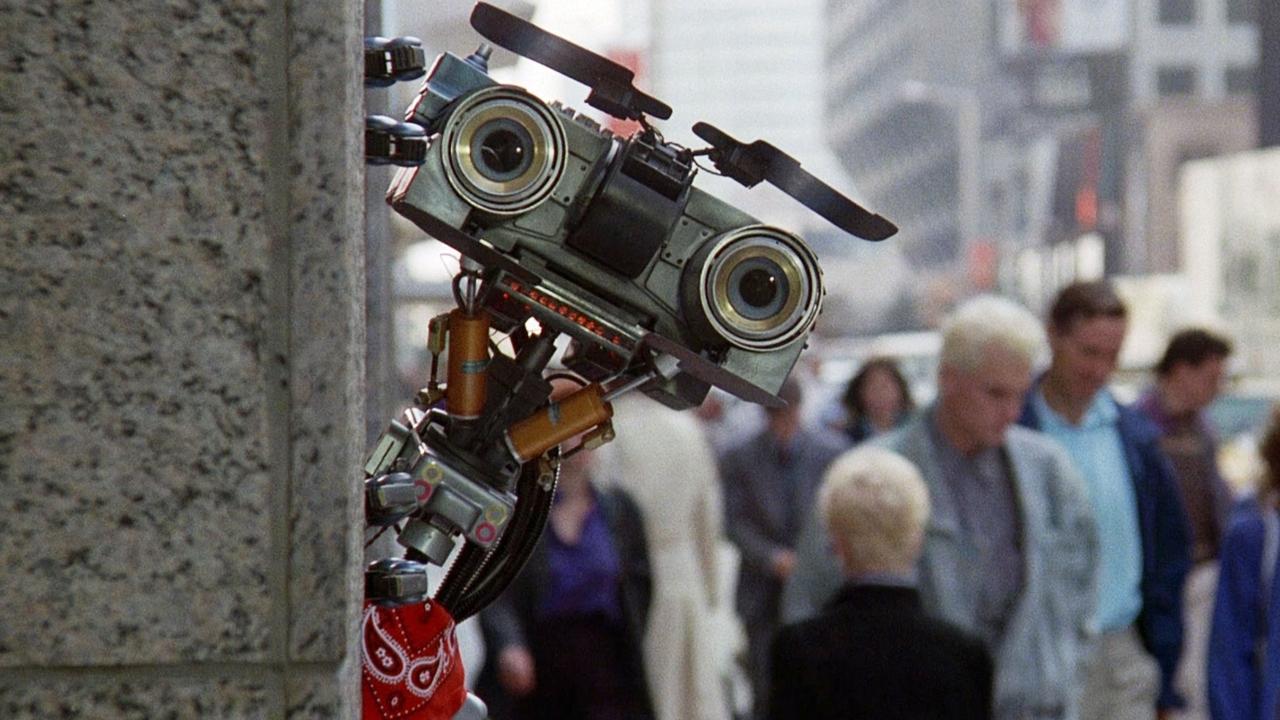

Twenty minutes into John Badham's 1986 sci-fi comedy, a tank-treaded robot named Number 5 gets struck by lightning and starts reading the encyclopedia. It's a goofy premise. Most of the time, these mid-80s high-concept movies relied entirely on the gimmick, but the cast of Short Circuit actually managed to ground the absurdity in something that felt, well, human. Even the robot.

Looking back, the chemistry shouldn't have worked. You had a Brat Pack staple, a veteran character actor who usually played high-strung neurotics, and a lead actress who spent half the movie talking to a pile of metal. Yet, it became a cult classic. People still quote "Input!" or "Number 5 is alive!" decades later. It’s weird how nostalgia works, but honestly, it’s the specific choices made by this ensemble that kept the movie from being just another forgotten piece of Reagan-era fluff.

Ally Sheedy and the Art of Talking to Nothing

Ally Sheedy was fresh off The Breakfast Club and St. Elmo’s Fire when she took the role of Stephanie Speck. At the time, she was basically the "it" girl for soulful, slightly misunderstood outcasts. In Short Circuit, she has to play a woman who treats a military-grade weapon like a stray puppy.

It’s harder than it looks. Sheedy wasn’t acting against a CGI character added in post-production. She was talking to a puppet. A very expensive, very complex puppet designed by Syd Mead, but a puppet nonetheless. Her performance is the heart of the film because if you don't believe she believes Number 5 is a person, the whole movie collapses. She brings this genuine, wide-eyed sincerity to the role that prevents the "woman befriends a robot" trope from feeling creepy or totally insane. She was actually the first person cast, and John Badham has noted in several retrospectives that her ability to emote toward a machine was what sold the studio on the project.

The Fisher Stevens Controversy and Modern Eyes

When we talk about the cast of Short Circuit, we have to address Ben Jabituya. Fisher Stevens played the goofy, pun-loving Indian scientist. Now, if you watch it today, it’s uncomfortable. Stevens is a white actor from Chicago using "brownface" and a thick, exaggerated accent.

Back in '86, this was a common—if lazy—Hollywood trope. Stevens has been remarkably candid about this in recent years. In an interview with Entertainment Weekly, he admitted that at the time, he was a struggling actor who was told the role was written for an Indian man, but they couldn't find anyone "right" (a classic Hollywood excuse). He actually went to India, lived there for a bit, studied the culture, and tried to ground the character. But looking back through a 2026 lens, it’s a glaring example of 80s casting blind spots. Despite the problematic nature of the casting, Stevens' comedic timing with Steve Guttenberg provided most of the film's "odd couple" energy.

Steve Guttenberg: The King of the 80s Everyman

Then there's Steve Guttenberg. You couldn't throw a rock in 1986 without hitting a movie he was in. Police Academy, Cocoon, Three Men and a Baby—the guy was everywhere.

In Short Circuit, he plays Newton Crosby. He’s the brilliant but socially awkward designer of the S.A.I.N.T. robots. Guttenberg has this specific brand of "nice guy" energy that makes him incredibly likable, even when he's being a bit of a jerk to Stephanie. He’s the skeptic. He represents the audience. We need him to be convinced that the robot is sentient so that we can be convinced. His transition from "it's just a machine with a short circuit" to "this is a living being" is the actual narrative arc of the film.

The Unsung Hero: Tim Blaney

If you’re looking for the most important member of the cast of Short Circuit, it’s a guy most people never saw on screen. Tim Blaney.

He was the voice of Johnny 5.

Usually, in movies like this, the voice is recorded months later in a dark booth. Not here. Blaney was on set, hiding behind furniture or tucked into corners, performing the lines in real-time. This allowed Sheedy and Guttenberg to actually improvise. When Number 5 gets distracted or reacts to a bug, that’s Blaney operating the head and providing the voice simultaneously. It gave the robot a soul. The "S-V-P" (Special Vehicles Program) crew, led by Eric Allard, handled the physical movements, but Blaney gave it the personality. Without his frantic, curious, and slightly high-pitched delivery, Number 5 would have just been a cold piece of hardware.

The Supporting Players: Villains and Bureaucrats

- G.W. Bailey (Captain Skroeder): Fresh off playing Harris in Police Academy, Bailey did what he does best: the blustering, incompetent antagonist. He’s the "shoot first, ask questions never" military guy. He provides the necessary stakes.

- Austin Pendleton (Howard Marner): He’s the corporate head of NOVA Robotics. Pendleton is a master of the "stressed-out middle manager" archetype. He’s not evil; he’s just worried about the bottom line and his reputation.

- Brian McNamara (Frank): Stephanie’s jerk ex-boyfriend. He’s basically there to be the human contrast to the robot’s innocence.

Why the Chemistry Worked (And Why the Sequel Didn't)

There’s a reason Short Circuit 2 felt different, and it wasn't just the lack of Steve Guttenberg and Ally Sheedy. The original film focused on the discovery of life. The cast of Short Circuit was built around the theme of "nurture." Stephanie Speck nurtures the robot; Newton Crosby learns to value life over logic.

When the sequel shifted the focus entirely to Ben (Fisher Stevens) in the big city, it lost that grounded, rural, almost ET-like atmosphere. The first movie works because it feels small and personal. It’s a road movie where one of the passengers happens to be a laser-armed tank. The interaction between the leads—Sheedy's warmth, Guttenberg's skepticism, and Stevens' comic relief—created a balanced triangle that the sequel lacked.

The Technical Cast: The Robots

We can’t ignore the fact that there were actually several "Johnny 5s" on set. It wasn't just one machine. There was a "hero" robot used for close-ups, which was fully motorized. Then there were "stunt" versions that could be pushed or rigged for explosions.

Syd Mead, the legendary visual futurist who worked on Blade Runner and Tron, designed the robot. He wanted it to look functional, not cute. The "eyebrow" flaps were a stroke of genius. By moving those metal plates, the puppeteers could make Johnny 5 look sad, surprised, or angry. It’s a masterclass in minimalist character design. The puppeteers themselves are effectively part of the cast, working in tandem to create a performance that feels singular.

Actionable Takeaways for Movie Buffs

If you're revisiting the film or researching the production, keep these points in mind to appreciate the craft behind the scenes:

- Watch the eyes: Pay attention to the shutters and "eyebrow" plates on Number 5. Most of his "acting" is done through these tiny mechanical movements, which were controlled by off-camera technicians in real-time.

- The "Brownface" Context: If you're discussing the film in a modern context, it's a primary example used in film studies regarding the history of South Asian representation (or lack thereof) in 1980s cinema.

- Location Scouting: The movie was filmed largely in Astoria, Oregon—the same town where The Goonies was shot. The lush, Pacific Northwest backdrop was chosen specifically to contrast with the cold, metallic nature of the robot.

- Puppetry vs. CGI: Compare the "weight" of Johnny 5 to modern CGI robots. Because he was a physical object, the actors had to physically navigate around him, which creates a sense of spatial reality that digital characters often lack.

The cast of Short Circuit managed to take a script that could have been a forgettable Saturday morning cartoon and turned it into a film with genuine pathos. Whether it was Ally Sheedy's earnestness or the frantic puppetry of a dozen technicians, they made us believe that a machine could actually fear being "disassembled."

To truly understand the impact of the film, look for the 25th-anniversary interviews where the actors discuss the difficulty of the Oregon shoot. The rain was constant, the robots frequently short-circuited (ironically), and yet the cast maintained a sense of play that translates perfectly to the screen. It remains a definitive piece of 80s sci-fi because it prioritized the "alive" part over the "robot" part.