He lived in Guadalajara. He died in Arévalo. Between those two points in 13th-century Spain, Moses de León changed the trajectory of Western mysticism forever. Honestly, if you’ve ever seen a "Kabbalah string" on a celebrity's wrist or heard someone talk about the "Tree of Life," you're looking at the ripple effects of this one man’s life. But here’s the kicker: for centuries, people didn't even know his name was the one they should be looking for.

They were looking for Shimon bar Yochai.

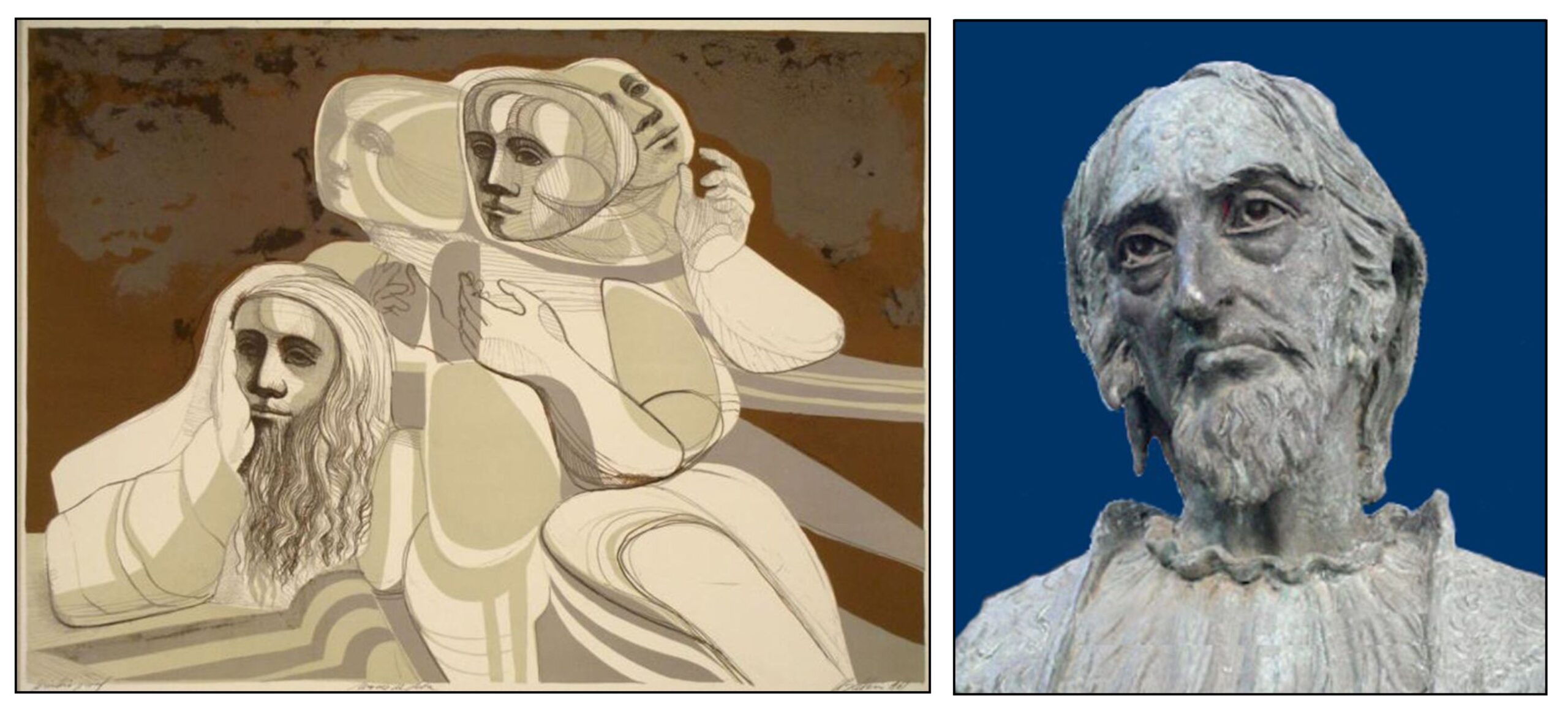

Moses de León was a scholar, a wanderer, and—depending on who you ask—either the greatest channeler of ancient wisdom or one of the most successful literary "forgers" in history. He claimed he was merely the scribe for a 2nd-century sage. Modern academics, starting with the legendary Gershom Scholem, tend to think otherwise. They see de León as the primary author of the Zohar, the "Book of Splendor."

The Mystery of the Zohar’s Arrival

Imagine it’s the 1280s. You’re a Jewish scholar in Castile. Suddenly, these manuscripts start circulating. They’re written in an eccentric, somewhat "artificial" Aramaic. They don't look like the legalistic Talmudic debates you're used to. They are wild. They talk about the inner life of God, the eroticism of the divine spheres, and the secret layers of the Torah.

Moses de León claimed he found an ancient book written by Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai (Rashbi) while the latter was hiding in a cave from the Romans a thousand years earlier. It was a perfect story. People wanted to believe it.

But things got weird after Moses died in 1305.

A wealthy man named Isaac of Acre traveled to Spain to find the original manuscript. He met Moses’ widow. He expected to see an ancient parchment. Instead, the widow reportedly told him that there was no ancient book. She claimed her husband had written it all "from his own head" to provide for his family because people would pay more for "ancient" wisdom than for a contemporary's thoughts.

🔗 Read more: Dating for 5 Years: Why the Five-Year Itch is Real (and How to Fix It)

Did she say it? Maybe. Isaac of Acre’s diary is the source for this, and even that is a layer of historical hearsay. Some believe she was just bitter or broke. Others think she was the only one telling the truth.

Why Moses de León Matters Right Now

You might wonder why we’re talking about a medieval Spanish rabbi in 2026. Basically, it’s because Moses de León gave us a language for the soul that didn't exist before him. Before the Zohar became mainstream, Jewish thought was often split between strict legalism and the cold, Aristotelian philosophy of Maimonides.

De León (or his circle) brought the "feeling" back.

He described the Sefirot—ten attributes of God. This wasn't just dry theology. It was a map of human psychology. When you talk about Chesed (loving-kindness) or Gevurah (strength/restraint), you’re using the framework he popularized. He turned the Torah into a love letter. To him, every word of scripture was a garment. If you only look at the garment, you miss the body. If you only look at the body, you miss the soul.

He was a master of the "long game." By attributing his work to an ancient authority, he ensured its survival. If he had published it as "The Musings of Moses from Guadalajara," it probably would have been forgotten in a decade. Instead, it became the "Bible of the Kabbalah."

The Linguistic Smoking Gun

Scholars like Scholem spent years dissecting the Aramaic in the Zohar. They found something fascinating. It wasn't the Aramaic spoken in 2nd-century Palestine. It was a version of Aramaic that felt... Spanish.

💡 You might also like: Creative and Meaningful Will You Be My Maid of Honour Ideas That Actually Feel Personal

- It used grammatical structures that mirrored medieval Spanish (Castilian).

- It misunderstood certain terms that a 2nd-century local would have known perfectly.

- It referenced events and ideas that didn't exist until the Middle Ages.

Does this make him a fraud? Not necessarily. In the medieval world, "pseudepigrapha" (writing under a deceased person's name) was a common literary device. It wasn't always seen as lying; sometimes it was seen as "tuning in" to that person's spirit. De León might have genuinely believed he was channeling the essence of Shimon bar Yochai.

A Life of Transition

Moses didn't start with the Zohar. He was a prolific writer under his own name first. He wrote Sefer Ha-Rimmon (The Book of the Pomegranate) in 1287. He wrote Or Zarua. These books are important because they show his evolution. You can see the themes of the Zohar starting to sprout in his "official" works. It's like watching a musician's early demos before they drop a masterpiece album.

He lived a nomadic life toward the end. He was often short on cash. This financial pressure is what critics point to when they say he "invented" the Zohar for profit. But writing thousands of pages of some of the most complex, beautiful, and deeply moving mystical prose in human history just for a few coins? That seems like a stretch. You don't write the Zohar just to pay the rent. You write it because you have a vision that’s burning a hole in your mind.

What Most People Get Wrong About Him

There’s this idea that Moses de León was a lonely hermit. He wasn't. He was part of a vibrant, intellectual "Kabbalistic circle" in Castile. This was a time of intense cultural exchange and intense pressure. The Reconquista was moving forward. Jewish communities were feeling the squeeze.

In this environment, de León’s work offered a "secret" power. It suggested that when a person performs a mitzvah (a commandment), they aren't just following a rule—they are literally "mending" the cracks in the universe. He gave people agency at a time when they felt powerless.

He also redefined the feminine side of God. The Shekhinah. In the Zohar, the divine presence is often described in feminine terms, longing for union with the masculine. This was radical. It was bold. And it likely came from the mind of a man who lived through the age of the Troubadours and courtly love in Spain.

📖 Related: Cracker Barrel Old Country Store Waldorf: What Most People Get Wrong About This Local Staple

How to Understand His Legacy Today

If you want to actually "use" the insights of Moses de León, you don't need to be a scholar of medieval Aramaic. You just need to look at his core message: The world is not what it seems.

- Look for the "Sod" (Secret): De León taught that everything has four layers: Pshat (literal), Remez (hinted), Drash (homiletical), and Sod (secret). Next time you read a story or watch a movie, ask yourself: what’s the "Sod" here? What is the hidden energy underneath the plot?

- Radical Empathy: Because de León viewed all souls as being connected to the same divine source, your actions affect everyone. This is "butterfly effect" spirituality.

- Complexity is Okay: The Zohar is notoriously difficult. It’s contradictory. It’s messy. Moses de León’s life was also messy. He teaches us that spiritual truth doesn't have to be "clean" to be true.

Practical Steps for the Curious

If this rabbit hole interests you, don't just take my word for it. The history is still being written as we find new fragments.

- Read the "Sefer Ha-Rimmon": It’s one of the few books he definitely signed his name to. It’s like a "lite" version of his mystical theories.

- Compare the Styles: If you look at the Zohar alongside de León's Hebrew works, look for the word "soul" (neshamah). The way he describes the soul's journey is a fingerprint that spans across his entire bibliography.

- Visit the Geography: If you're ever in Spain, go to Guadalajara. Walk the streets where he likely walked. There is a specific energy to the Castilian landscape—vast, dry, and intense—that mirrors the prose of the Zohar.

Moses de León died on his way home from the royal court. He never saw the Zohar become the foundation of Hasidism, the inspiration for Renaissance magicians, or the subject of Madonna’s studies. He died a relatively obscure, controversial figure.

But he left behind a map of the invisible. Whether he "found" it or "made" it doesn't change the fact that for millions of people, the map works. He proved that a single person, sitting in a small room in Spain, can rewrite the spiritual DNA of the world. He was a bridge-builder between the human and the divine, even if he had to hide behind a 2nd-century mask to do it.

To explore this further, start by looking into the works of Elliot Wolfson or Moshe Idel. These modern scholars have taken Scholem's foundation and added layers of nuance that make Moses de León feel less like a "forger" and more like a visionary artist using the tools available to him in a dangerous century.