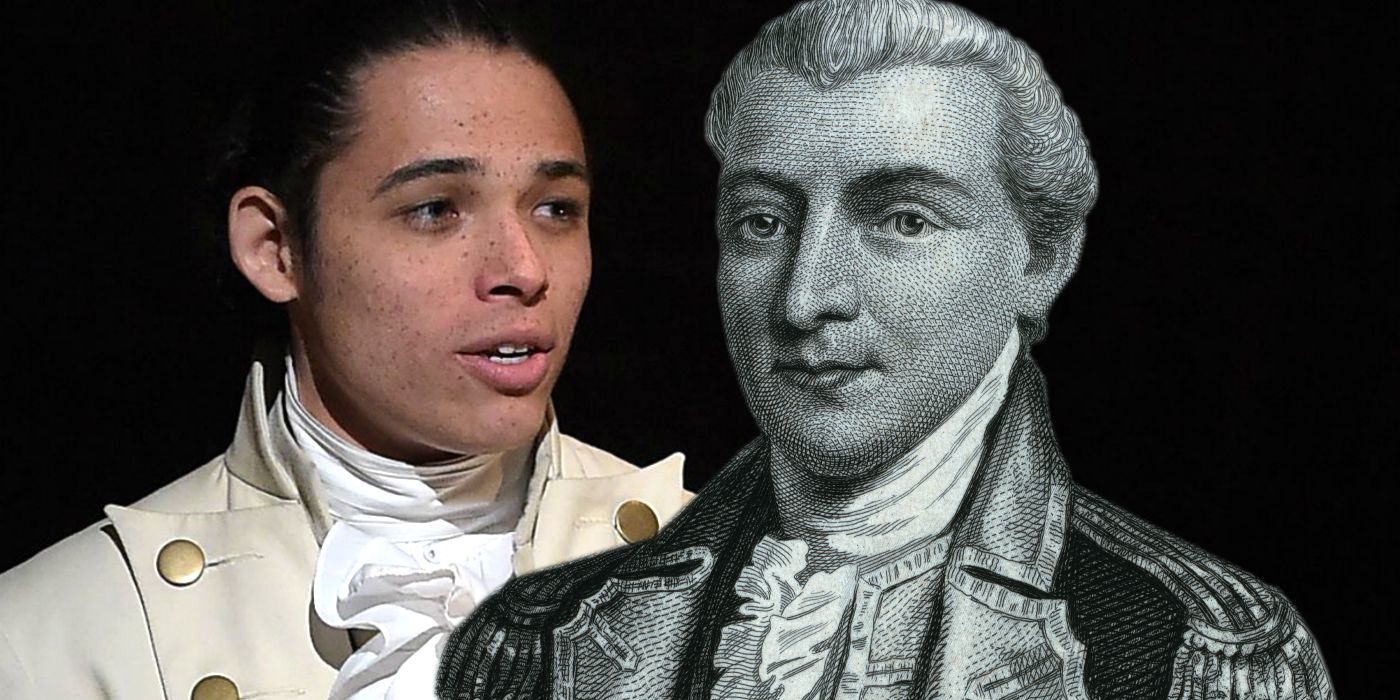

You’ve probably heard the name in a Broadway rap. Or maybe you saw his face on a grainy historical sketch while scrolling through history memes. Honestly, most people today know exactly who was John Laurens because of a certain musical, but the real man was a lot more complicated—and arguably more radical—than a catchy chorus suggests.

He wasn't just Hamilton’s best friend. He wasn't just a soldier. John Laurens was a wealthy South Carolinian who decided to spit in the face of his own upbringing to fight for something that almost nobody in his social circle wanted: the end of slavery in America.

He was brilliant. He was reckless. Some might say he had a bit of a death wish.

Born in 1754 into one of the wealthiest slave-trading families in the colonies, Laurens had every reason to sit back and collect rent. Instead, he spent his short life trying to burn down the very systems that made him rich. If you want to understand the true friction at the heart of the American Revolution, you have to look at John.

The Man Behind the Legend: Early Life and Education

Laurens wasn't some scrappy underdog. His father, Henry Laurens, was literally the President of the Continental Congress and one of the most powerful men in the South. Because of this, John got the "grand tour" education. He studied in London and Geneva. He was refined. He was cultured. He spoke fluent French, which came in pretty handy later when he had to go beg King Louis XVI for more money to keep the American rebellion from collapsing.

But Europe changed him. While he was studying law at the Middle Temple in London, he started getting these ideas. Ideas that didn't mesh with a father who owned thousands of human beings.

He wrote to his father constantly. He challenged the hypocrisy of fighting for "liberty" while keeping people in chains. It wasn't a popular stance. Actually, it was a social death sentence in South Carolina. But John didn't seem to care about social standing. He cared about the "purity" of the cause.

The "Aide-de-Camp" Era: Hamilton and Washington

In 1777, Laurens joined George Washington's staff as an aide-de-camp. This is where the history books usually get exciting. This was the original "braintrust." You had Alexander Hamilton, the Marquis de Lafayette, and John Laurens all working in the same cramped tents.

They were young. They were idealistic. And they were incredibly close.

💡 You might also like: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

The letters between Hamilton and Laurens have kept historians busy for decades. Hamilton wrote things to John like, "I wish Christopher's (his servant) had been mine... I would have sent him to you to tell you how much I love you." Whether their relationship was romantic or just an intense 18th-century "bromance" is still debated by scholars like Ron Chernow and Thomas Foster. Regardless of the label, they were soulmates in the struggle.

Laurens was the one who did the dirty work. He was the one who fought a duel with Charles Lee to defend Washington's honor. He was the one who was always the first to volunteer for the most dangerous scouting missions. He was brave to the point of being a liability. Washington loved him for it, but he also worried about him.

The Black Battalion: A Dream Ahead of Its Time

If you really want to know who was John Laurens, you have to look at his 1779 proposal. This was his "magnum opus," and it's also his greatest tragedy.

Laurens proposed raising a regiment of 3,000 enslaved men in South Carolina. The deal was simple: if they fought for the Continental Army, they would be granted their freedom at the end of the war.

Think about the time. This wasn't 1863. This was 1779.

The South Carolina legislature absolutely hated it. They didn't just reject the idea; they were horrified by it. To them, arming enslaved people was a nightmare scenario. Even though the British were literally invading their state, the wealthy planters preferred the risk of British rule over the risk of an armed Black population.

Laurens didn't give up. He went back to the statehouse again and again. He argued that "we have sunk the Africans & their descendants below the standard of humanity," and it was time to make it right. He lost every single time.

The Diplomat and the Final Battle

In 1781, Laurens was sent to France. The Revolution was broke. Dead broke.

📖 Related: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

He didn't use the usual diplomatic channels. He basically bypassed the ministers and went straight to the King. He told Louis XVI that if France didn't send a massive infusion of cash and a fleet, the Americans were going to lose. It worked. He returned to America with 2.5 million livres in silver and a fresh fleet of ships that would eventually help win the Battle of Yorktown.

He was at Yorktown, too. He helped negotiate the terms of the British surrender. He was at the top of the world.

But he couldn't stop.

The war was basically over after Yorktown, but small skirmishes were still happening in the South. Laurens went back to South Carolina. On August 27, 1782, during a minor, almost meaningless skirmish at the Combahee River, John Laurens was shot.

He was 27.

He died in the mud of a riverbank just a few miles from where he grew up. He died fighting for a state that had rejected his most important idea.

Why We Still Talk About Him

History is full of people who did what was expected of them. John Laurens is fascinating because he did the exact opposite. He was a man of the 18th century who saw the 19th and 20th centuries coming.

He wasn't perfect. He was stubborn. He was arguably elitist in his own way. But his commitment to the idea that liberty meant liberty for everyone makes him one of the most singular figures of the era.

👉 See also: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

When Hamilton found out John had died, he was devastated. He wrote that the world had lost "a valuable citizen" and he had lost a friend whose "integrity and truth" were unmatched.

Understanding the Nuance

It is easy to paint Laurens as a modern-day progressive, but he was still a product of his time. He didn't believe in immediate, total social equality in the way we understand it today. He believed in merit and military service as the path to citizenship. However, compared to his peers, he was light-years ahead.

- The Family Conflict: His father, Henry, eventually came around to John's way of thinking—at least partially. After John's death, Henry emancipated some of the people he enslaved, citing John's influence.

- The Military Record: Laurens was involved in almost every major engagement: Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, and the Siege of Charleston.

- The Legend: Because he died so young, we never saw him become a politician. We never saw him have to make the messy compromises that Hamilton, Jefferson, and Madison made. He remains "frozen in time" as the pure, idealistic martyr of the Revolution.

Actionable Insights: Learning from the Life of John Laurens

If you’re looking to dig deeper into the life of this fascinating figure, don't just stop at a soundtrack. Here is how you can actually engage with the history of John Laurens:

Read the Primary Sources

The "Hamilton-Laurens" correspondence is public domain. Reading their actual letters—not just the summaries—gives you a visceral sense of the pressure these young men were under. You can find these at the National Archives (Founders Online).

Visit the Sites

If you're in South Carolina, visit the Combahee River area or the site of his family's former plantations (like Mepkin Abbey). Seeing the geography helps you understand why his "Black Battalion" plan was so terrifying to the local establishment of the time.

Study the Dissent

Don't just read about the winners. Look into the South Carolina legislative records from 1779 to 1782. Understanding why they said "no" to Laurens provides a massive amount of context for the Civil War that would happen 80 years later.

Analyze the "What If"

Think about how American history might have changed if the Black Battalion had been approved. It would have created a class of thousands of armed, free Black veterans in the heart of the South in the 1780s. The ripple effects on the Constitution and the expansion of slavery would have been seismic.

John Laurens wasn't just a sidekick. He was a man who challenged the very foundations of his own life for a version of America that we are still trying to build. That’s why his name still rings out today.

Next Steps for Historical Research:

- Check out "The Papers of Henry Laurens" for a look at the father-son dynamic that shaped John's world.

- Explore the "Found Founders" series by various university presses which often highlight the secondary figures like Laurens who did the heavy lifting of the war.

- Evaluate the Southern Theater of the war—often overlooked in favor of New England battles, the South is where the war was actually decided and where Laurens' impact was most felt.