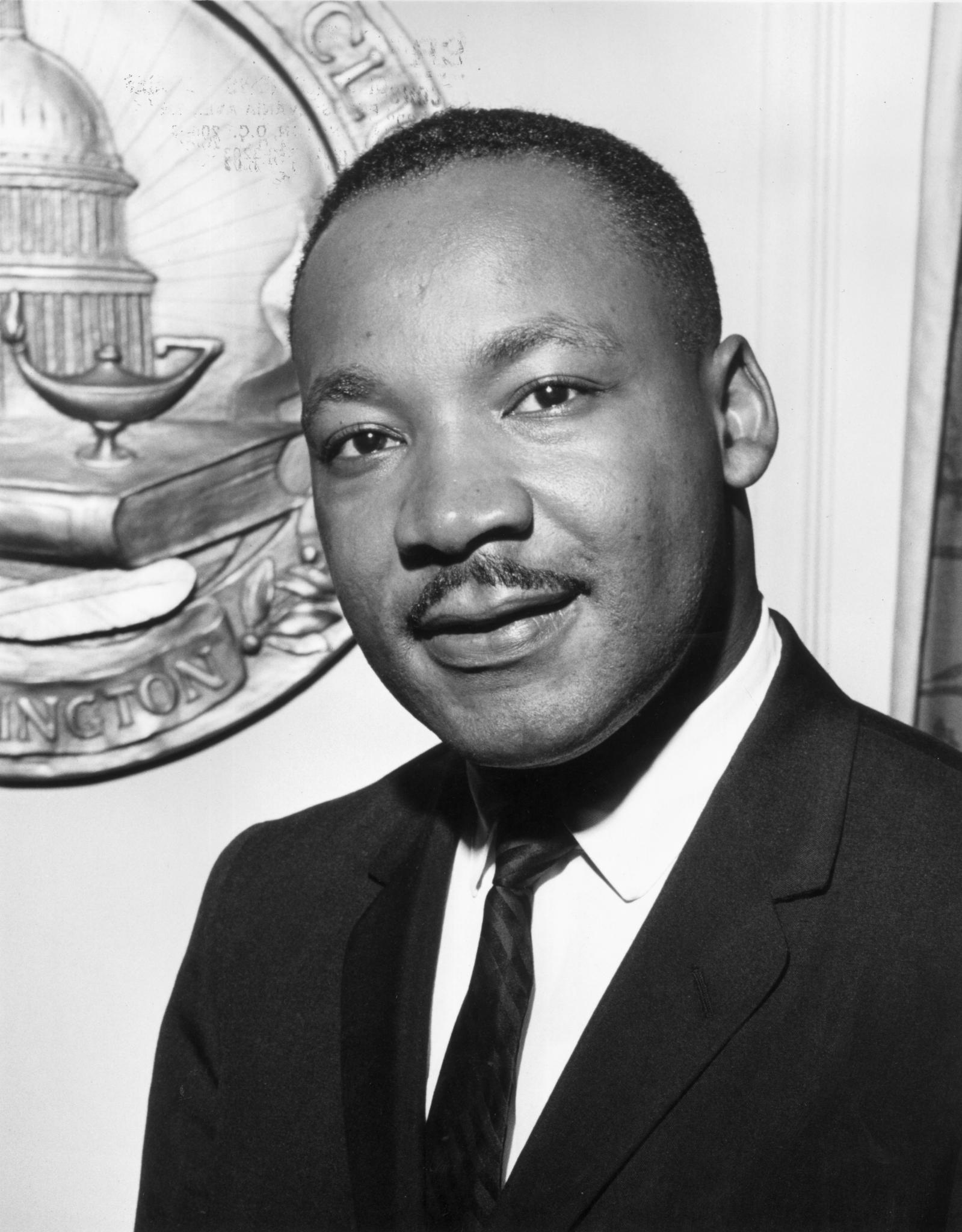

You’ve seen the grainy footage of the "I Have a Dream" speech a thousand times. Every January, social media feeds fill up with the same three or four quotes about love and light. But if you really want to know who was Dr Martin Luther King Jr, you have to look past the "monument" version of the man. He wasn't just a peaceful dreamer. He was a radical, a brilliant strategist, and, by the end of his life, one of the most hated men in America.

It’s wild how history polishes people.

We forget that at the time of his assassination in 1968, his disapproval rating was nearly 75%. He wasn't some universally beloved figure who just asked nicely for rights. He was a massive disruption to the status quo. Born Michael King Jr. in 1929—his father later changed both their names after being inspired by the Protestant reformer Martin Luther—he grew up in the middle-class "Black Mecca" of Auburn Avenue in Atlanta. This wasn't a man who happened upon leadership by accident. He was groomed for it, but the path he took was far more dangerous than his family ever expected.

The intellectual engine behind the movement

Most people think King’s non-violence was just a moral choice. It was actually a deeply researched political tactic. During his time at Morehouse College and later Crozer Theological Seminary, he was obsessed with finding a way to make religion relevant to social change. He read Thoreau on civil disobedience. He studied Marx and felt that while communism was flawed, the critique of the gap between wealth and poverty was dead on.

Then he found Gandhi.

It clicked. The idea of "Satyagraha" or soul-force wasn't about being passive. It was about using non-violence as a weapon to expose the brutality of the oppressor. Honestly, it’s a terrifying strategy if you think about it. You’re basically saying, "I will let you hit me so that the world can see how ugly you are." That takes a level of discipline that most of us can't even imagine. When the Montgomery Bus Boycott kicked off in 1955 after Rosa Parks was arrested, King was only 26 years old. He was the "new guy" in town, which is partly why he got picked to lead—he didn't have any enemies yet.

The Montgomery shift and the rise of a leader

The boycott lasted 381 days. Think about that. People walked to work in the rain, heat, and cold for over a year. King’s house was bombed during this time. His wife, Coretta, and their newborn baby were inside. He didn't quit. Instead, he told a crowd of angry supporters to put their guns away. This was the moment the world started to realize who was Dr Martin Luther King Jr—he was someone who could hold back a literal riot with just his voice.

He wasn't always confident, though. There’s a famous story about him sitting at his kitchen table in Montgomery, late at night, terrified. He’d received another death threat. He said he felt the presence of God telling him to stand up for righteousness. Whether you're religious or not, that moment of human vulnerability makes the rest of his life feel much more real. He wasn't a superhero. He was a guy who was scared and did it anyway.

✨ Don't miss: Who Has Trump Pardoned So Far: What Really Happened with the 47th President's List

More than just "The Dream"

By 1963, King was the face of the Civil Rights Movement. The March on Washington is what everyone remembers, but the stuff that happened behind the scenes was incredibly messy. There was massive infighting between different groups like the NAACP, the SCLC (King’s group), and the younger, more radical SNCC. King was the bridge. He had this unique ability to talk to white liberals in the North and sharecroppers in the South without losing his soul in the process.

But the "Dream" speech actually signaled a turning point where he started getting more radical. If you read his "Letter from Birmingham Jail," written on scraps of newspaper and toilet paper while he was locked up, he’s not yelling at the KKK. He’s yelling at the "white moderate." He says that the person who prefers "order" to "justice" is the biggest stumbling block to freedom.

He was tired of being told to "wait."

The pivot that cost him everything

If King had stopped after the Voting Rights Act of 1965, he probably would have been a hero to everyone. But he didn't. He started looking at the North. He moved his family into a dilapidated apartment in the slums of Chicago to protest housing discrimination. He realized that giving a man the right to sit at a lunch counter doesn't mean much if he can't afford the hamburger.

This is where he started to lose the support of the White House.

In 1967, at Riverside Church in New York, he gave a speech titled "Beyond Vietnam." He called the U.S. government the "greatest purveyor of violence in the world today." He linked racism, materialism, and militarism together as the "triple evils."

Suddenly, his allies vanished.

🔗 Read more: Why the 2013 Moore Oklahoma Tornado Changed Everything We Knew About Survival

Lyndon B. Johnson was furious. The mainstream media, including the New York Times and Washington Post, slammed him. They told him to stick to "civil rights" and stay out of foreign policy. But King saw them as the same thing. He saw poor Black kids and poor white kids being sent to die for a "freedom" they didn't even have at home. This version of King—the anti-war, pro-labor radical—is the one we usually don't talk about in school.

The Poor People's Campaign and Memphis

By 1968, King was exhausted. He was suffering from what many now believe was clinical depression. He was being hounded by the FBI; J. Edgar Hoover was obsessed with destroying him, sending him anonymous letters suggesting he should take his own life.

Yet, he was planning the "Poor People's Campaign."

He wanted to bring a multiracial army of poor people to Washington, D.C., to camp out on the Mall until Congress passed an "Economic Bill of Rights." He was talking about guaranteed basic income and massive government spending on jobs. He was effectively challenging the entire economic structure of the United States.

Then came Memphis.

He went there to support striking sanitation workers. They were protesting horrific conditions—two workers had recently been crushed to death by a malfunctioning garbage truck. On the night of April 3, 1968, he gave his final speech, the "Mountaintop" speech. He sounded like a man who knew his time was up. "I've seen the Promised Land," he said. "I may not get there with you."

The next evening, he was shot on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. He was 39.

💡 You might also like: Ethics in the News: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the "Dreamer" label is dangerous

When we ask who was Dr Martin Luther King Jr, and we only answer with "the man who wanted kids to hold hands," we do a disservice to his legacy. It makes him safe. It makes him easy to digest.

King was a threat.

He was a threat to the racial hierarchy, yes, but also to the economic and military status quo. He was a man of deep faith who believed that love was the most powerful political force in existence, but he also knew that love without power is "anemic and sentimental." He wanted a total revolution of values.

The legacy you can actually use

So, what do we do with this? If you’re looking to apply King’s life to today, it’s not about just being "nice" to people. It’s about understanding the systems that keep people down.

- Look at the intersections. King realized late in life that you can't fix racism without looking at poverty. If you're trying to solve a problem in your community, look for the root cause, not just the symptom.

- Strategy over emotion. King didn't just show up and protest. Every move was calculated. The locations were chosen for their likelihood of garnering media attention. The marchers were trained in how to react to violence. Success requires more than passion; it requires a plan.

- The "Difficult Middle." King was constantly attacked from both sides. Radicals called him "Uncle Tom" for being too slow, and conservatives called him a "Communist" for being too fast. True leadership often means standing in that uncomfortable gap where no one is happy with you.

Dr. King wasn't a marble statue. He was a smoker who liked soul food and laughed at dirty jokes and stayed up too late worrying about his kids. He was a person who chose to be brave when it would have been much easier to stay home. We don't need to worship the man; we need to study the work. The "Promised Land" he talked about wasn't a destination we reached in 1964. It’s a goal that requires constant, uncomfortable work.

Understanding the full scope of his life means realizing that the struggle for justice isn't a straight line. It's a messy, circular, and often lonely process. But as he famously liked to paraphrase: the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. It just doesn't bend on its own. It requires people to put their weight on it.

To truly honor his memory, start by reading his later works, like Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? It’s there that you’ll find the King who was truly ready to change the world—and the one who remains most relevant to the challenges we face right now.

Practical Steps for Deeper Understanding

- Read the primary sources: Skip the biographies for a moment and read "Letter from Birmingham Jail" and the "Beyond Vietnam" speech in their entirety.

- Visit the sites: If you can, go to the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis (built into the Lorraine Motel) or the King Center in Atlanta. Seeing the physical spaces where this happened changes your perspective.

- Support local labor: King’s final act was supporting a strike. If you want to follow his lead, look at economic justice issues in your own backyard.

- Analyze the "Moderate" stance: Challenge yourself to see where you might be prioritizing "order" over "justice" in your own life or career.