You probably recognize the name from a history textbook or maybe a random street sign in Boston. But honestly, most people don’t realize just how much of a lightning rod Charles Sumner actually was. He wasn't just some stuffy politician in a waistcoat. He was arguably the most hated—and most loved—man in the United States Senate during the mid-19th century.

Who was Charles Sumner? Simply put, he was the moral conscience of the North, a radical abolitionist who refused to shut up about the evils of slavery, even when his life depended on it.

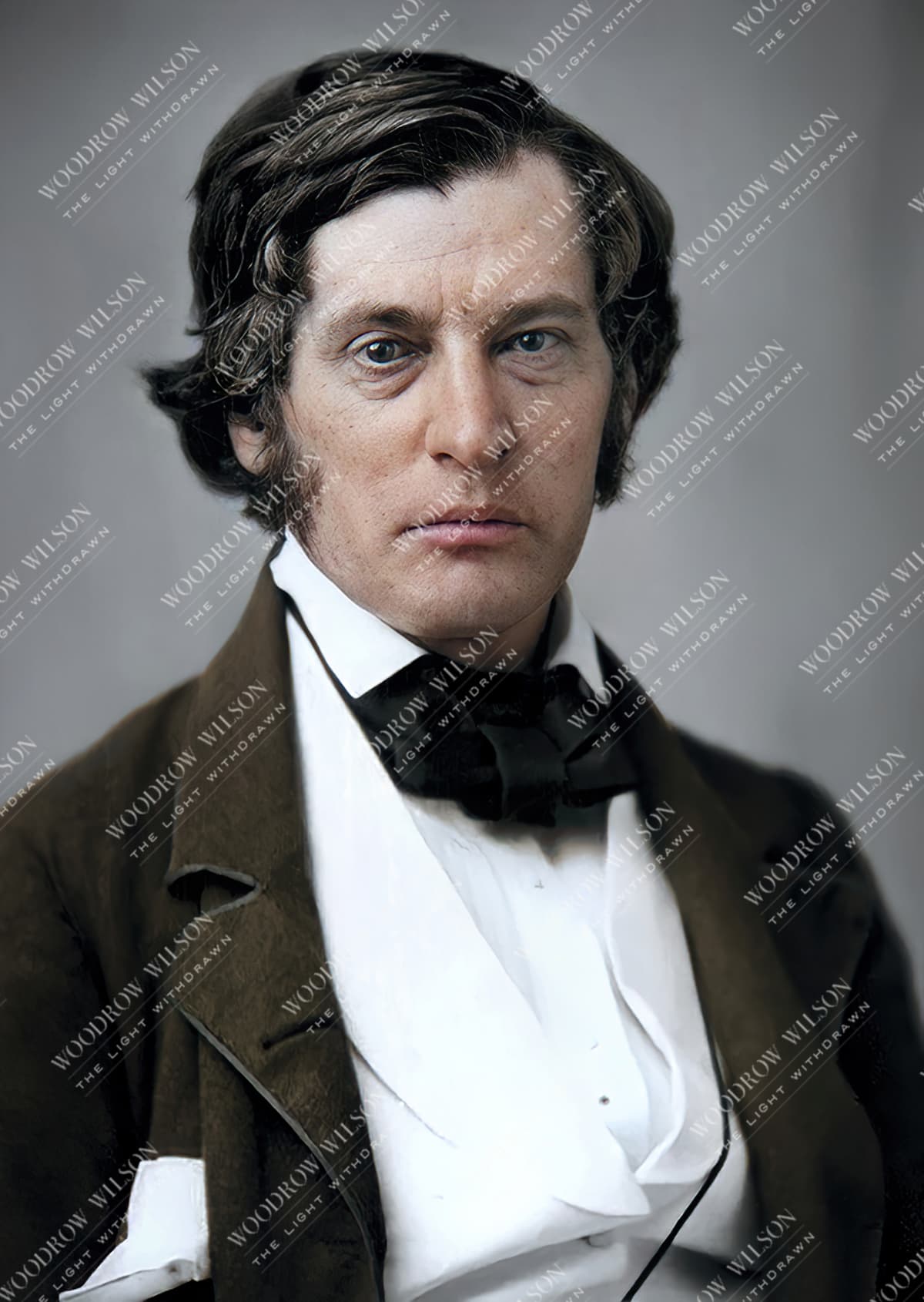

He stood 6'4", a literal giant of a man with a booming voice and a Harvard education that he used like a sledgehammer. While other politicians were busy trying to "compromise" their way out of a brewing Civil War, Sumner was calling slavery a "monstrous injustice." He didn't care about making friends in Washington. He cared about being right.

The Day the Senate Turned Violent

If you want to understand the sheer intensity surrounding this man, you have to look at May 22, 1856. This is the defining moment of his career.

Two days earlier, Sumner delivered a blistering five-hour speech titled "The Crime Against Kansas." He didn't hold back. He specifically insulted Senator Andrew Butler of South Carolina, mocking Butler’s physical speech impediment and comparing his devotion to slavery to a love affair with a "harlot." It was personal. It was nasty. And in the code of the Old South, it required a response.

A few days later, Butler’s cousin, Representative Preston Brooks, walked into the Senate chamber. Sumner was at his desk, pinned down by the heavy furniture, franking copies of his speech to mail to constituents. Without much warning, Brooks began raining down blows on Sumner’s head with a thick, gold-headed gutta-percha cane.

It wasn't a scuffle. It was a brutal assault.

✨ Don't miss: Middle East Ceasefire: What Everyone Is Actually Getting Wrong

Sumner, blinded by his own blood, eventually ripped the desk right out of the floor in a desperate attempt to escape. He collapsed, unconscious. While Northern newspapers screamed about "Southern Chivalry" being a myth, Southerners sent Brooks new canes to replace the one he broke over Sumner’s head.

This single event basically signaled that the time for debate was over. If Senators were beating each other bloody in the Capitol, the rest of the country wasn't far behind.

Why He Was So Polarizing

Sumner was a "Radical Republican" before the term even fully existed. He didn't just want to stop the spread of slavery; he wanted it dead. Everywhere.

He was a founder of the Free Soil Party. Later, he became a pillar of the Republican Party. What made him different from someone like Abraham Lincoln—at least early on—was his refusal to be pragmatic. Lincoln was a lawyer and a politician who moved slowly. Sumner was a moralist. To him, there was no middle ground on human bondage.

He was annoying to his colleagues. Let's be real. Even his allies found him arrogant and pedantic. He had this habit of quoting Greek and Latin for hours, basically reminding everyone in the room that he was the smartest guy there. But that rigid, unyielding personality was exactly what the abolitionist movement needed.

His Vision for a New America

While the Civil War was raging, Sumner was already looking at what came next. He was one of the first to argue for "State Suicide"—the idea that by seceding, Southern states had forfeited their rights and should be treated as conquered territories. Why did this matter? Because it gave the federal government the power to enforce civil rights.

🔗 Read more: Michael Collins of Ireland: What Most People Get Wrong

He pushed for:

- The immediate emancipation of all enslaved people.

- The right for Black men to vote, long before it was popular.

- Integrated schools in Massachusetts (he actually argued the Roberts v. City of Boston case in 1849).

- The Civil Rights Act of 1875, which was way ahead of its time.

He saw the "Declaration of Independence" as a literal legal document. To him, "all men are created equal" wasn't a suggestion. It was the law.

The Complicated Relationship with Lincoln

It’s easy to think of the Civil War-era Republicans as a monolith, but Sumner and Lincoln clashed constantly. Sumner was the guy whispering—or shouting—in Lincoln’s ear that he wasn't going fast enough.

When Lincoln was hesitant to issue the Emancipation Proclamation because he was worried about the border states, Sumner was there telling him it was a military and moral necessity. They were friends, sort of. Lincoln respected him, but he also found him exhausting.

There’s a great story about Sumner visiting the White House and refusing to leave until Lincoln listened to his latest grievance. Lincoln reportedly said that Sumner was his "idea of a bishop"—high-minded, rigid, and slightly out of touch with the messy reality of politics. Yet, after Lincoln was assassinated, it was Sumner who stood by his bedside.

The Long Road to Recovery and the Final Act

The 1856 beating didn't just keep him out of the Senate for a few weeks. It took him three years to return to his seat full-time. He suffered from what we would now recognize as Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and severe PTSD. He spent years in Europe undergoing agonizing medical treatments, including "firing"—a practice where doctors burned the skin on his back to "stimulate" his nervous system.

💡 You might also like: Margaret Thatcher Explained: Why the Iron Lady Still Divides Us Today

The empty chair he left in the Senate became a powerful symbol for the North. It was a silent reminder of Southern aggression. When he finally returned in 1859, he was just as fiery as before. He didn't learn "decorum." He doubled down.

In his later years, he broke with his own party. He hated the corruption of the Ulysses S. Grant administration. He felt that the Republican Party was losing its moral compass and becoming too focused on money and power. This eventually led to him being stripped of his chairmanship of the Foreign Relations Committee. It was a bitter end for a man who had given his health and career to the party’s cause.

What History Gets Wrong About Him

Common misconceptions often paint Sumner as just a victim or a one-note orator. He was actually a brilliant diplomat. As Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he was instrumental in keeping Great Britain and France from recognizing the Confederacy. If they had intervened, the South might have won. Sumner’s expertise in international law—and his friendships with European elites—basically saved the Union on the global stage.

People also tend to forget that he was a pioneer in what we now call "intersectionality." He saw the struggle for Black rights, women's rights, and the rights of the poor as interconnected. He wasn't perfect, and he could be incredibly condescending, but his vision for America was more inclusive than almost any of his peers.

Why Charles Sumner Matters in 2026

We live in a time of extreme polarization. Looking back at Sumner reminds us that this isn't new. He shows us that sometimes, being "difficult" and "uncompromising" is the only way to move the needle on justice.

If you're looking for actionable ways to engage with his legacy, start here:

- Read the "Crime Against Kansas" Speech: It's long, and the references are dated, but the raw passion is still palpable. You can find it in the Library of Congress digital archives.

- Visit the Old State House in Boston: His influence is all over the city. Check out the statue of him in the Public Garden—it captures that stern, unyielding gaze perfectly.

- Study the Civil Rights Act of 1875: It was eventually overturned by the Supreme Court in 1883, but it served as the blueprint for the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Understanding why it failed helps explain the "Jim Crow" era that followed.

- Support Brain Injury Research: Sumner’s life was fundamentally altered by a TBI. Organizations like the Brain Injury Association of America carry on the work of understanding the long-term effects of the kind of trauma he endured.

Charles Sumner was a man of words who was met with a man of violence. He didn't win every battle, and he died feeling like the country was failing his vision of true equality. But without his refusal to compromise, the American experiment might have collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions long ago. He wasn't just a senator; he was the man who forced America to look in the mirror and reckon with its greatest sin.