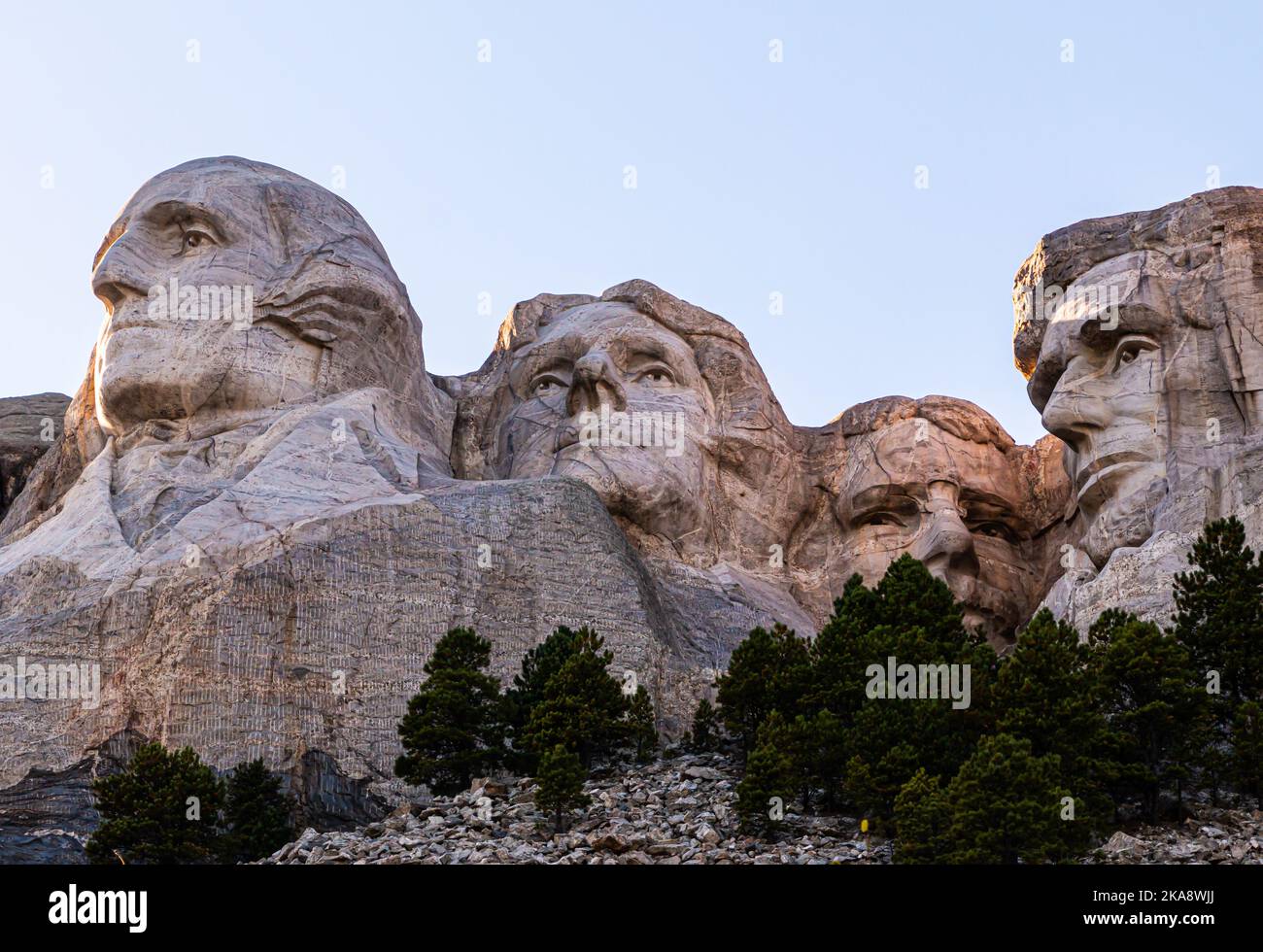

You’ve seen the photos a thousand times. Four massive heads staring out over the Black Hills of South Dakota. It’s iconic. It’s huge. But if you ask the average person who sculpted Mount Rushmore, they might fumble for a name or just guess "the government."

The short answer is Gutzon Borglum. He was the mastermind, the ego, and the primary artist. But honestly, saying just one guy did it is like saying one guy built the Great Pyramid. It’s a bit of a stretch. Behind Borglum was a small army of 400 workers, a fiery Italian immigrant named Luigi Del Bianco, and a whole lot of dynamite.

The story isn't just about art. It’s about a man who was obsessed with scale, a project that nearly ran out of money every other week, and a massive engineering headache that took fourteen years to finish.

The Man with the Ego: Gutzon Borglum

Gutzon Borglum wasn't exactly a wallflower. He was a student of Rodin, the guy who did The Thinker, and he brought that same "go big or go home" energy to everything he touched. Before he ever set foot in South Dakota, he was working on Stone Mountain in Georgia. That project ended in a disaster—Borglum got into a massive fight with the organizers, smashed his clay models, and fled the state to avoid being arrested.

Classic artist drama, right?

When Doane Robinson, a South Dakota historian, wanted to create a tourist attraction to bring people to the Black Hills, he reached out to Borglum. Robinson originally wanted western heroes like Buffalo Bill Cody or Lewis and Clark. Borglum basically laughed at that. He told Robinson that if they were going to carve a mountain, it had to be something of national importance. It had to be the Presidents.

He chose George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt. Why those four? Washington represents the birth of the nation. Jefferson, the expansion (the Louisiana Purchase). Lincoln, the preservation. And Roosevelt? He was the choice for development and the Panama Canal. Plus, Borglum just really liked Teddy.

The Secret Weapon: Luigi Del Bianco

For a long time, the history books ignored the "Chief Carver." Borglum was the designer, sure, but he wasn't the one hanging off a cliff with a chisel every single day. That was Luigi Del Bianco.

Del Bianco was an Italian immigrant who understood stone in a way most people don't. He wasn't just a laborer; he was a classically trained stone carver. Borglum specifically requested him because Del Bianco knew how to give the eyes of the Presidents that "spark."

If you look closely at the eyes of the Presidents, they look alive. That’s because Del Bianco carved a physical column of granite inside the pupil to catch the light. It’s a trick of the trade that makes a piece of rock look like it's looking back at you. For decades, Del Bianco’s family fought to have his contribution recognized. It wasn't until the 1990s and early 2000s that the National Park Service finally gave him the credit he deserved.

90% Dynamite

When people think about who sculpted Mount Rushmore, they usually imagine guys with hammers and chisels. In reality, 90% of the mountain was removed with dynamite.

You can't exactly "sculpt" 450,000 tons of granite by hand. Not in fourteen years.

The workers used a process called "honeycombing." They would drill holes very close together to a certain depth and then blast the rock away. It was incredibly dangerous work. These guys were sitting in "bosun chairs," which were basically wooden swings held up by steel cables.

Imagine being 500 feet in the air, the wind is howling, and you're holding a jackhammer that weighs more than you do. Oh, and someone is about to set off explosives a few yards away.

Remarkably, despite the heights, the dynamite, and the falling rocks, nobody died during the construction of Mount Rushmore. Not one person. That’s almost unheard of for a project of that scale in the 1920s and 30s.

The Jefferson Problem

Things didn't always go according to plan. Originally, Thomas Jefferson was supposed to be to the right of George Washington (from the viewer's perspective). They spent two years carving him there.

Then, they realized the stone was bad.

The granite was full of fissures and cracks. It was literally crumbling under the tools. Borglum made a radical decision: they blasted Jefferson off the mountain. Just blew him up. They had to start over and put him on Washington’s left side. If you look at the mountain today, you can see where the rock looks a bit scarred—that’s the remains of the first Jefferson attempt.

The Hall of Records: A Secret Room?

Borglum had a vision that went way beyond just faces. He wanted to build a massive "Hall of Records" behind the heads. It was supposed to be a vault containing the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and all the most important documents of American history.

He started drilling a tunnel behind Abraham Lincoln's head.

The government, however, wasn't thrilled. They told him to stop messing around with "extra" rooms and finish the faces. Congress was footing the bill, and they were tired of Borglum's constant budget overruns. The tunnel was left as a dead end, a 70-foot-long cave that tourists aren't allowed to enter.

In 1998, a repository of records was finally placed in the floor of the hall's entrance, but it’s nowhere near the grand chamber Borglum imagined. It’s basically a box in a hole.

Why It Ended When It Did

Borglum died in March 1941, just months before the project was officially "finished." His son, Lincoln Borglum, took over.

Lincoln didn't do much more carving. The project was supposed to show the Presidents down to their waists. If you look at the original models in the visitor center, you’ll see they have coats, hands, and buttons.

But World War II was looming. The United States was shifting its focus to the conflict in Europe and the Pacific. The funding dried up instantly. Lincoln Borglum looked at the faces, decided they were "good enough," and called it a day in October 1941.

That’s why the sculpture looks so rugged at the bottom. It's technically unfinished.

The Controversy: Native American Perspective

You can't talk about who sculpted Mount Rushmore without talking about where it was sculpted. The Lakota Sioux call this mountain Tunkasila Sakpe Paha, or the Six Grandfathers Mountain.

For them, the carving isn't a masterpiece of art; it’s a desecration of sacred land. The Black Hills were granted to the Sioux in the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868. However, once gold was discovered, the U.S. government took the land back.

🔗 Read more: The Kimpton Brice Hotel Savannah: Why This Former Coca-Cola Plant Is Still The Best Place To Stay

This tension led to the creation of the Crazy Horse Memorial just a few miles away. That project, started by Korczak Ziolkowski (who actually worked briefly at Rushmore), is meant to be a response to the four Presidents. It’s still being carved today and will be much larger than Mount Rushmore if it's ever finished.

Visiting Today: What You Need to Know

If you're planning to see the work of Borglum and his crew, don't just look at the faces.

- Go to the Sculptor's Studio: You can see the original 1:12 scale models. They help you realize how much of the original plan was lost when the money ran out.

- Walk the Presidential Trail: It gets you as close to the base of the mountain as possible. You’ll see the massive "talus slope," which is the pile of rocks blasted off the mountain. They never moved them because it would have cost too much.

- The Evening Lighting Ceremony: It’s a bit patriotic/theatrical, but seeing the faces lit up against the pitch-black sky is genuinely impressive.

Actionable Takeaways for Your Trip

- Arrive early or late: Between 10:00 AM and 3:00 PM, the place is a zoo. If you get there at sunrise, the light hits the faces perfectly for photos, and you'll have the place to yourself.

- Check the sun: Because the faces look Southeast, they are best lit in the morning. By late afternoon, Roosevelt and Lincoln start to fall into shadow.

- Don't skip Custer State Park: It’s right next door. You can see bison, granite "needles," and some of the best driving roads in America.

- Look for the "Spark": Use binoculars to look at the eyes. Try to spot the granite columns Luigi Del Bianco carved to create that lifelike glint.

The question of who sculpted Mount Rushmore has many layers. It was Borglum’s vision, Del Bianco’s skill, the workers' bravery, and a government's checkbook. It’s a complicated monument on even more complicated land. Knowing the grit and the drama behind the stone makes looking up at those 60-foot faces a lot more interesting than just seeing a picture in a textbook.