You probably learned in elementary school that Alexander Graham Bell sat in a room, spilled some acid, and shouted for Mr. Watson. It’s a clean story. It’s also kinda incomplete. When you ask who invented the telephone, the answer depends entirely on whether you’re talking about the guy who got to the patent office first or the people who actually figured out how to move a human voice through a copper wire.

The history of the phone is messy. It’s full of lawsuits, desperate poverty, and a literal race to the patent office that came down to a matter of hours. Honestly, if a few things had gone differently in the 1870s, we might all be talking about "Gray-phones" or "Meucci-boxes" today.

The 1876 Patent Office Sprint

On February 14, 1876, Alexander Graham Bell’s lawyer filed a patent application for the telephone. That same day—only a few hours later—an inventor named Elisha Gray filed a "caveat," which is basically a document saying "I’m working on this idea, so don't give a patent to anyone else yet."

It was a disaster for Gray.

Because Bell’s paperwork was processed first, he got the credit. But here’s the weird part: Bell’s initial patent didn’t even include a working diagram of a telephone that could actually transmit clear speech. It was mostly about "multiplexing" telegraph signals. Gray, on the other hand, had a specific design for a water transmitter. Within days of seeing Gray’s filing (yes, Bell was allowed to look at it), Bell incorporated a similar liquid transmitter into his own experiments. That’s when he finally got the famous "Mr. Watson, come here" sentence to work.

It feels a bit sketchy, right?

Antonio Meucci and the Poverty Problem

Long before Bell or Gray were even thinking about wires, an Italian immigrant named Antonio Meucci was building a "teletrofono" in his home in Staten Island. The year was 1854. Meucci needed a way to talk to his wife, Esther, who was paralyzed by rheumatoid arthritis and confined to her bedroom.

He built a system. It worked.

Meucci wasn’t a businessman; he was a cash-strapped inventor. In 1871, he filed a caveat for his talking telegraph. But to keep a caveat active, you had to pay $10 every year. By 1874, Meucci was so broke he couldn't afford the ten bucks. He let the caveat lapse. Two years later, Bell filed his patent.

In 2002, the U.S. House of Representatives actually passed a resolution (H.Res. 269) acknowledging Meucci’s work. They basically admitted that if Meucci could have paid that $10 fee, Bell wouldn't have been able to get his patent. Life is brutal like that.

Why the Telegraph Was the Real Parent

You can't understand who invented the telephone without looking at the telegraph. By the 1870s, the telegraph was the king of communication, but it had a massive limitation: you could only send one message at a time over a single wire. It was a bottleneck.

Every inventor was obsessed with the "harmonic telegraph." The idea was that if you sent different tones at different frequencies, you could stack multiple messages on one wire.

Bell was a teacher of the deaf. He understood acoustics. He realized that if you could send multiple frequencies for a telegraph, you could theoretically send the complex frequencies of the human voice. He wasn't trying to build an iPhone; he was trying to fix a hardware issue for Western Union.

The Johann Philipp Reis Factor

We also have to talk about Johann Philipp Reis. In 1861, this German scientist built a machine that could transmit musical notes and even some muffled speech. He called it the "Telephon."

The problem? It wasn't "continuous."

His device worked by breaking the circuit every time the sound membrane vibrated. It was "make-and-break." This works for a steady hum, but it destroys the nuances of human speech. Bell’s genius—or the genius he refined from others—was the "undulating current." This kept the circuit closed but varied the intensity of the electricity. That’s the secret sauce that makes a phone a phone and not just a loud telegraph.

The Legal War of the Century

Once Bell had the patent, he didn't just sit back and relax. The Bell Telephone Company had to defend that patent in over 600 separate lawsuits. Everyone wanted a piece of the action. People claimed they had invented it first, that Bell had stolen the ideas, or that the patent was too broad.

Western Union, the giant of the era, even hired Thomas Edison to make a better version of the phone to put Bell out of business. Edison invented the carbon grain transmitter, which actually made the phone usable over long distances. Bell’s original version was faint and scratchy; Edison’s version is basically what we used in landlines for the next century.

Eventually, Bell sued Western Union. And he won.

The courts generally landed on one specific logic: Bell was the first to successfully describe the method of using a continuous undulating current to transmit speech. Even if others had the "idea," Bell had the paperwork and the scientific theory that held up in front of a judge.

Complexity Over Simplicity

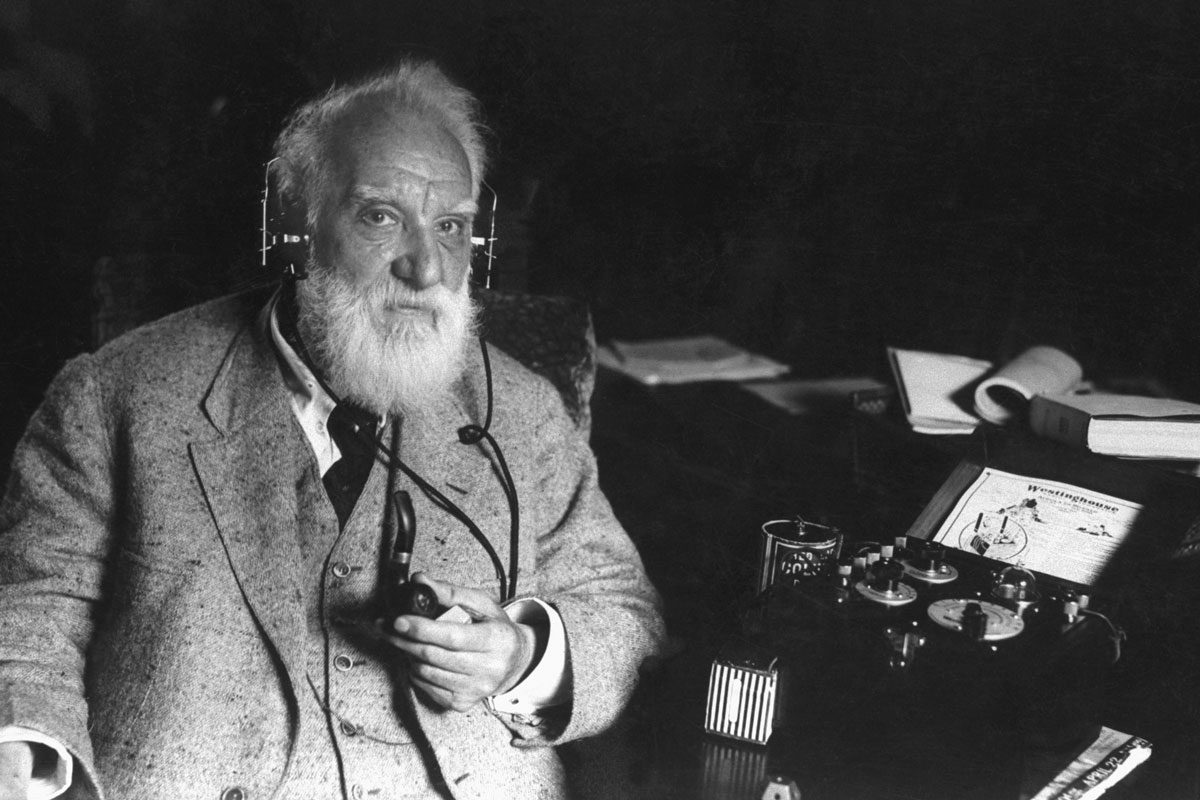

History likes heroes. It’s easier to put Alexander Graham Bell on a postage stamp than to explain a decade of overlapping experiments by Meucci, Gray, Reis, and Varley.

Bell was incredibly driven, well-funded, and legally savvy. He also genuinely cared about sound—his work with the deaf community gave him an edge in understanding how the human ear processes vibrations. But he wasn't a lone wizard. He was a man who crossed the finish line of a marathon that dozens of other people had been running for twenty years.

Facts to Keep Straight

- 1849: Antonio Meucci demonstrates a voice-communication device in Havana.

- 1861: Johann Philipp Reis produces a "Telephon" in Germany.

- 1876 (Feb 14): Bell’s patent application is filed at roughly 11:00 AM. Gray’s caveat is filed around 1:00 PM.

- 1876 (March 10): The first successful transmission of speech occurs using a design that looked suspiciously like Gray's.

- 1877: The first commercial telephone lines are installed.

What You Can Learn from the Telephone Race

If you're looking at the history of who invented the telephone as a lesson for today, the takeaway isn't just "be first." It’s "be complete."

Meucci had the tech but no money. Gray had the tech but was too slow with the paperwork. Reis had the tech but didn't understand the physics of the continuous current. Bell won because he combined the scientific theory, the legal protection, and the financial backing to turn an experiment into an industry.

To truly understand this history, look into the "Telephone Cases" of the late 19th century. They are a masterclass in how intellectual property works. You should also check out the Smithsonian’s archives on Elisha Gray; his "Musical Telegraph" is a wild piece of engineering that often gets ignored because he lost the big race.

Ultimately, the telephone didn't have one father. It had a neighborhood of inventors, and Bell was just the one who built the strongest fence around the yard.

📖 Related: How to Use an Application to Move Mouse Without Getting Flagged by IT

Next Steps for Deep Research:

- Read the 2002 Congressional Resolution 269: It provides a fascinating look at the evidence for Antonio Meucci's priority.

- Compare the "Liquid Transmitter" Sketches: Look at Bell's notebook entry from March 1876 alongside Gray's February caveat. The similarities are striking and remain a point of debate among historians.

- Explore the Carbon Microphone: Research Thomas Edison’s 1877 improvement. Without this specific component, the telephone would likely have remained a short-range novelty rather than a global communication tool.