You’ve seen the photos. Those stoic, heavy-browed faces staring out over the Pacific, half-buried in the soil of a tiny, windswept island. For decades, the internet and late-night "documentaries" have tried to convince us that these monoliths were dropped there by spacecraft or carved by some lost continent’s refugees. It makes for a great story. Honestly, though? The real answer to who made the stone heads of Easter Island is much more impressive because it involves actual human grit, ingenious engineering, and a culture that managed to thrive in total isolation.

The people behind the statues are the Rapa Nui.

They weren't "mysterious" ghosts. They were Polynesians. Specifically, they were master navigators who paddled thousands of miles across open water to find this speck of land. Around 1200 AD (though dates are always a bit of a moving target in archaeology), these settlers arrived and began one of the most ambitious construction projects in human history.

The Rapa Nui: Not Just Sculptors, But Engineers

When we talk about who made the stone heads of Easter Island, we’re talking about a complex society divided into clans. These weren't just random carvings. Each statue, or moai, was commissioned by a specific group to honor a deceased ancestor or a high-ranking chief. Think of them as living faces of the dead. They weren't just looking at the sea; they were looking back at the villages, spreading a kind of spiritual protection called mana over the people.

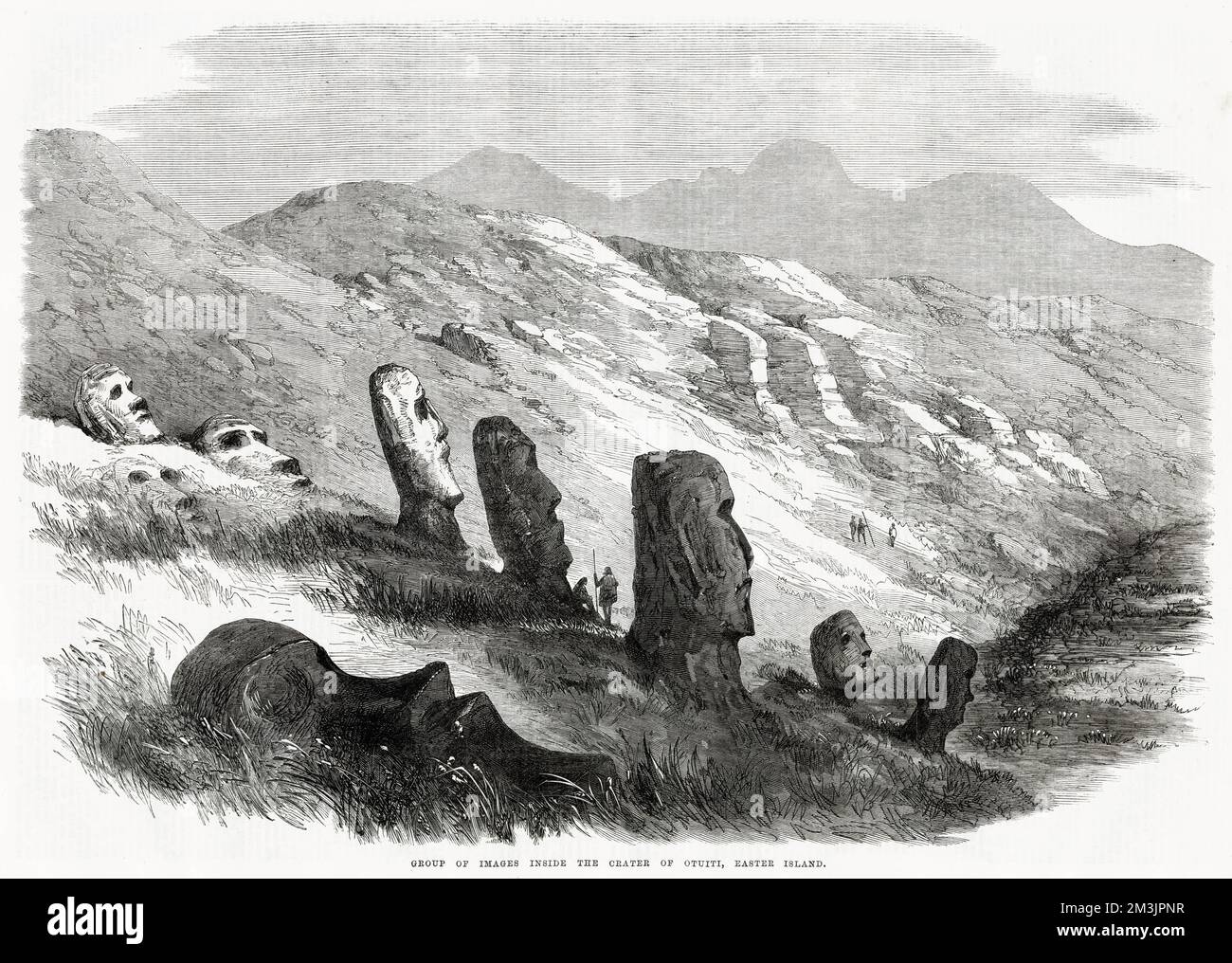

The carving didn't happen all over the island. Almost every single one of the nearly 900 statues came from one place: Rano Raraku.

It’s a volcanic crater. The rock there is called tuff—basically compressed volcanic ash. It’s soft enough to carve with stone tools but hardens once it’s exposed to the air. If you visit today, you can still see unfinished moai still attached to the bedrock. It looks like the workers just dropped their tools and walked away for lunch 500 years ago and never came back. It’s eerie.

How they actually moved the things

This is where the "aliens" crowd usually loses their minds. "How could primitive people move a 14-ton block of stone across miles of rugged terrain?" they ask.

👉 See also: Minneapolis Institute of Art: What Most People Get Wrong

The Rapa Nui had a simple explanation: the statues walked.

For a long time, Western scientists laughed at that. They tried dragging them on sleds. They tried rolling them on logs (which, to be fair, probably happened too). But in 2011, archaeologists Terry Hunt and Carl Lipo showed that the oral traditions were likely literal. By using three heavy ropes and a rhythmic rocking motion, a small group of people could make a moai "walk" forward. It waddles. It's a bit like moving a refrigerator by tilting it from side to side. Because the statues have a D-shaped base and a center of gravity that leans forward, they are literally designed to be moved this way.

It wasn't magic. It was physics.

The Evolution of the Moai Style

The earliest statues were actually quite small. They looked more like humans. Over time, as clans competed for prestige, the moai got bigger, taller, and more stylized.

You’ve probably noticed some of them wear "hats." These are called pukao. They aren't actually hats, though—they represent topknots of hair, which was a sign of status. They were made from a different stone, a red scoria from a separate quarry called Puna Pau. Imagine the logistics: you carve a massive head in one crater, "walk" it ten miles to a platform (an ahu), then go to another quarry to get a multi-ton red hairpiece and somehow hoist it onto the head without a crane.

The skill level is insane.

✨ Don't miss: Michigan and Wacker Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong

- Tools: They used toki, which are handheld basalt chisels.

- Eyes: The statues weren't "blind." Once a moai reached its ahu, the workers carved out the eye sockets and inlaid them with white coral and red scoria pupils. This "awakened" the statue.

- Scale: The average moai is about 13 feet tall, but the largest one ever successfully erected, Paro, stands nearly 33 feet high.

What Happened to the People Who Made Them?

There’s a popular myth that the Rapa Nui committed "ecocide"—that they cut down all their trees to move statues and then starved to death in a civil war. It’s a neat cautionary tale, but modern research suggests it’s mostly wrong.

While the island did lose its forests, the Rapa Nui were incredibly resilient. They switched to "lithic mulching," which is basically covering the ground with broken rocks to keep the soil moist and fertilized. They didn't just collapse.

The real tragedy came later.

In the 1860s, Peruvian slave raiders arrived. They kidnapped about 1,500 people, including the king and the educated priestly class who could read Rongorongo (the island's unique script). Then came smallpox. By 1877, the population of Rapa Nui had plummeted to just 111 people.

That is why the statues stopped being made. It wasn't a mystery or a supernatural disappearance. It was a human catastrophe.

Common Misconceptions About the Stone Heads

A lot of people think the heads are just... heads.

🔗 Read more: Metropolitan at the 9 Cleveland: What Most People Get Wrong

They aren't. Every "head" on Easter Island is actually a full body. The reason they look like just heads in most famous photos is that the ones on the slopes of Rano Raraku have been buried by centuries of shifting soil and erosion. When archaeologists like Jo Anne Van Tilburg excavated them, they found torsos, hands with long fingers resting on the bellies, and even detailed carvings on the backs that look like tattoos or loincloths.

Also, they don't face the ocean. This is a big one. Almost all moai face inland to watch over the people. Only the seven statues at Ahu Akivi face the sea, and they were likely used for astronomical or navigational purposes.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Traveler

If you’re planning to see who made the stone heads of Easter Island for yourself, you can't just wander around. The island is a UNESCO World Heritage site and a protected National Park.

- Hire a local Rapa Nui guide. Seriously. Don't just read the plaques. The oral history passed down through families adds a layer of depth you won't find in a textbook. Plus, the money stays in the community.

- Respect the Tapu. "Tapu" is the origin of the word "taboo." Do not touch the statues. Don't even walk on the ahu (the stone platforms). The oil from your hands can damage the lichen and the stone, and it's deeply disrespectful to the ancestors.

- Visit Puna Pau. Most people skip the "hat" quarry, but it's where you see the sheer color contrast of the island's geology.

- Check out the Museum. The Sebastian Englert Anthropological Museum in Hanga Roa has the only original coral eye ever found. It changes how you look at the "blank" faces on the rest of the island.

The story of the Rapa Nui is one of survival and incredible craftsmanship. They took a tiny, treeless rock in the middle of nowhere and turned it into a gallery of giants. They didn't need help from the stars—they just needed stone, rope, and a whole lot of patience.

To truly understand the island, you have to look past the stone and see the people. Start by researching the current conservation efforts led by the Ma’u Henua indigenous community, who now manage the park. Supporting their work is the best way to ensure these "walking" giants stay standing for another thousand years.