If you ask a random person on the street who made the lightbulb first, they’re going to say Thomas Edison. It’s the standard answer. It’s what we’re taught in grade school. But honestly? It’s basically wrong. Or, at the very least, it's a massive oversimplification that ignores about eighty years of frantic, expensive, and often failed experiments by people whose names have been totally lost to history.

Edison didn't just wake up one day in 1879 and "invent" light.

He was actually quite late to the party. By the time Edison started tinkering in his lab at Menlo Park, the concept of electric light was already decades old. People had been trying to figure out how to keep a wire from burning up inside a glass jar since the Napoleonic Wars. The real story isn't about one lone genius in a lab; it's about a messy, legal-battle-filled race involving dozens of inventors across two continents.

The 1802 Mystery of Humphry Davy

Let's go back way further than you think.

In 1802, an English chemist named Humphry Davy created the first "incandescent" light. He didn't use a fancy filament or a vacuum bulb. He basically just hooked up a huge pile of batteries—what they called a "voltaic pile" back then—to a strip of platinum.

It worked. Sorta.

The platinum glowed. It produced light. But platinum is incredibly expensive, and the light didn't last long at all. It was more of a laboratory trick than a product you could actually use to read a book at night. Davy also invented the "Arc Lamp" a few years later, which was basically a continuous spark between two carbon rods. If you’ve ever seen a modern construction site at night with those blindingly bright blue-white lights, that’s the descendant of Davy’s arc lamp. They were great for lighthouses or street corners, but they were way too bright, hissed like a snake, and smelled like a campfire. You definitely didn't want one in your living room.

Why the Early Bulbs All Failed

The problem wasn't making light. That was the easy part. The hard part was making the light stay on for more than five minutes without the filament melting or the glass shattering.

For the next seventy years, inventors like Warren de la Rue and William Staite tried different materials. De la Rue used platinum coils in a vacuum. It was a brilliant move because a vacuum removes the oxygen that causes things to burn up. But again, the cost of platinum made it a non-starter for the average person. Imagine buying a lightbulb today that costs $5,000. No one’s doing that.

Then came Joseph Swan.

This is where the history gets really spicy. If you live in the UK, you might have been taught that Joseph Swan is the true inventor of the lightbulb. And honestly, he has a very strong case. By 1860, Swan had developed a bulb that used carbonized paper filaments. He even got a British patent for it. But he ran into a wall: the vacuum pumps of the 1860s were terrible. He couldn't get enough air out of the bulb, so the oxygen inside would eat the filament almost immediately.

He set the project aside for years.

While Swan was waiting for better pumps to be invented, a couple of Canadians named Henry Woodward and Mathew Evans were also having a go at it. In 1874, they patented a lamp that used carbon rods in a nitrogen-filled glass cylinder. They were onto something huge, but they couldn't get any funding. Nobody believed in them. They were broke.

Eventually, they sold their patent to a guy named Thomas Edison for $5,000.

The Menlo Park Marketing Machine

Edison wasn't just a scientist. He was a savvy businessman and, frankly, a bit of a shark.

When Edison entered the race in the late 1870s, he didn't start from scratch. He bought patents. He hired the best glassblowers and chemists. He looked at what everyone else was doing and realized that the "secret sauce" wasn't just the bulb—it was the entire system.

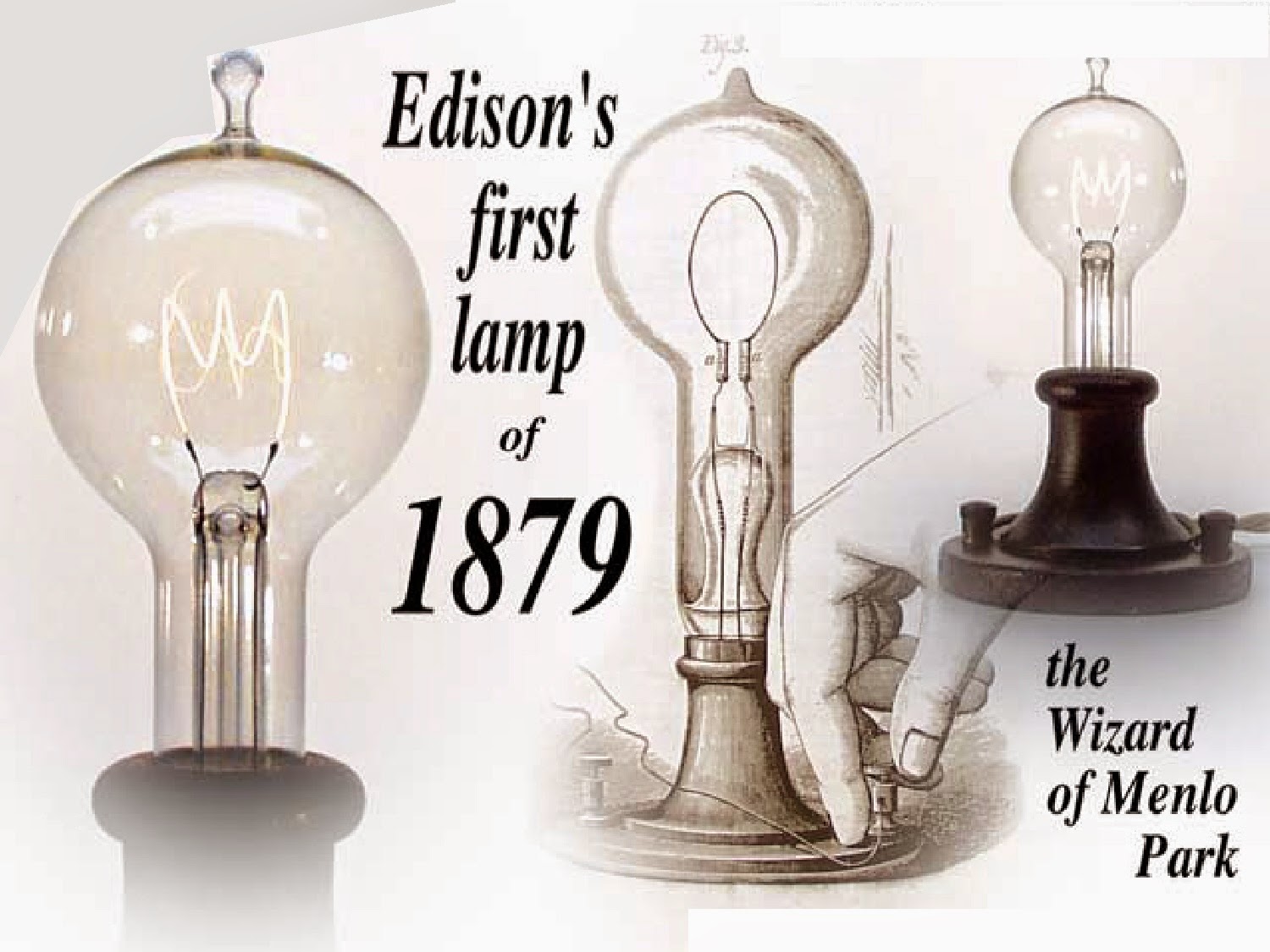

In 1879, Edison’s team discovered that a carbonized bamboo filament could last for over 1,200 hours. This was the "Aha!" moment. Bamboo. It sounds ridiculous, but the structural fibers of bamboo were perfect for holding up under intense heat.

But here’s the thing: Joseph Swan had also started working on his bulb again.

💡 You might also like: Where Is iPhone Backup Stored on PC? The Simple Truth for 2026

The Lawsuits That Changed Everything

Swan actually beat Edison to a public demonstration. He showed off his working bulb in Newcastle in early 1879, months before Edison’s big reveal. Naturally, the two men ended up in a massive legal feud over who made the lightbulb first.

Usually, in these situations, one person wins and the other goes bankrupt. But in a rare move of corporate pragmatism, they decided to join forces. They formed "Ediswan," a company that dominated the British market. This is why the "who invented it" question is so murky. If the two biggest guys in the field decide to share the credit (and the profits), the history books tend to get a bit confused.

The Real Breakdown of "Firsts"

If we’re being technical—and we should be—the "first" depends entirely on how you define the word "lightbulb."

- First Electric Light: Humphry Davy (1802). It was a glowing strip of metal.

- First Enclosed Vacuum Bulb: Warren de la Rue (1840). Too expensive to be practical.

- First Patent for a Carbon Bulb: Joseph Swan (1860/1878).

- First Commercial Success: Thomas Edison (1879).

Edison’s real genius wasn't the glass or the filament. It was the "Parallel Circuit." Before Edison, if you had a string of lights and one bulb blew out, the whole house went dark—kind of like those annoying old Christmas tree lights. Edison figured out how to wire them so each bulb functioned independently. He also built the power stations and the meters to charge people for the electricity.

He didn't just invent a bulb; he invented the utility bill.

The Forgotten Inventors

We also need to talk about Lewis Latimer.

Latimer was an African American inventor and draftsman who worked for Edison (and also for Alexander Graham Bell). While Edison’s bamboo filament was good, it was still a bit fragile. Latimer invented a way to manufacture carbon filaments that were much more durable. He wrote the first book on electric lighting and literally supervised the installation of public lights in New York, Philadelphia, and London.

Without Latimer, the lightbulb might have stayed a luxury item for the ultra-rich for much longer. He made it "street tough."

Then there's the mercury pump. Hermann Sprengel, a German chemist, invented the mercury vacuum pump in 1865. This is the unsexy part of the story that everyone skips. Without Sprengel’s pump, neither Swan nor Edison could have sucked enough air out of their bulbs to make them work. The pump was the real enabler of the lightbulb revolution.

What Actually Happened in 1879?

By the fall of 1879, the race was at a fever pitch. Edison was pouring money into his Menlo Park lab, which was basically the world's first R&D facility.

He wasn't just looking for a filament; he was looking for a "high resistance" filament. See, most people thought you needed low resistance to get a bright light. Edison did the math and realized that if you wanted to send electricity over miles of wire to thousands of homes, you needed a high-resistance bulb that used very little current.

On October 22, 1879, Edison’s team ran a test with a carbonized cotton thread. It stayed lit for 13.5 hours. A few days later, they pushed it to 40 hours. This is the date usually cited in textbooks, but it was just one milestone in a century-long marathon.

The Takeaway: It Was a Team Effort

History loves a "Great Man" narrative. It’s easier to put Thomas Edison on a stamp than it is to explain the complex overlap of twenty different scientists from five different countries.

👉 See also: The iPhone 17 Pro Max Barbie Edition: Is This Real or Just More Tech Rumor Noise?

But the truth is that the lightbulb was an iterative invention. It was a slow-motion explosion of ideas. Davy started the fire, Swan and de la Rue figured out the container, Sprengel provided the vacuum, Woodward and Evans provided the patent, and Edison provided the system (and the marketing).

If you're looking for one person to credit, you're going to be disappointed.

Actionable Insights for History and Tech Buffs

If you're researching this for a project or just want to be the "actually..." person at your next dinner party, here’s how to look at it:

- Check the Patents: Don't just look at the date of the "first" bulb. Look at the date of the first practical patent. Edison’s U.S. Patent 223,898 is the big one, but Swan’s British patents precede it.

- Distinguish Between Light and Systems: Most people confuse the invention of the bulb with the invention of the power grid. Edison’s "win" was the grid, not just the glass.

- Visit the Sources: If you're ever in New Jersey, Thomas Edison National Historical Park has the actual labs. Seeing the physical size of the vacuum pumps and the types of filaments they tested makes the struggle much more real.

- Acknowledge the Overlap: When discussing "who made the lightbulb first," always frame it as a transition. The transition from Arc Lamps to Incandescent Lamps is where the real drama happened.

The lightbulb didn't have one father. It had a whole neighborhood of parents, a few kidnappers, and one very good PR agent. Understanding that doesn't take away from Edison’s achievement—it just makes the reality of human progress look a lot more like it actually does: a messy, collaborative, and exhausting relay race.