It’s usually the first question people ask when they start getting into tailoring or textile history: who made the first sewing machine? Most Americans will shout "Isaac Singer!" from the back of the room. A few history buffs might chime in with Elias Howe.

They're all kinda wrong. Or, at the very least, they’re only telling you the end of a very long, very messy story involving riots, patent wars, and a French tailor who almost got murdered by a mob.

The truth? No single person just woke up and "invented" the sewing machine. It wasn't a "Eureka!" moment in a bathtub. It was a slow, painful evolution that spanned nearly a century, crossing borders from Germany to England to France before finally landing in the United States. If you’re looking for a name to put on a plaque, you’ve got about five different options depending on how you define "working machine."

The 1700s: Needlework without the hands

Back in 1755, a German guy named Charles Fredrick Wiesenthal took out a British patent for a mechanical needle. It had a point at both ends and an eye in the middle. That was it. No machine, just a needle meant for a machine that didn't exist yet. He basically invented the "engine" before the car was even a concept.

📖 Related: How to download music from Spotify on phone: The bits people usually miss

Then came Thomas Saint in 1790.

Saint was an English cabinet maker. He actually drew up detailed plans for a machine that could stitch leather. It had an awl to poke a hole and a fork to push the thread through. Here’s the kicker: nobody knows if he actually built it. His patent sat in the British Patent Office for 84 years before someone found it in 1874. When they tried to build a model based on his drawings, it didn't even work without heavy modifications.

It makes you wonder how many other inventions are just sitting in a dusty filing cabinet right now, waiting for a century to pass.

The tragic tale of Barthélemy Thimonnier

If we are being honest about who made the first sewing machine that actually functioned in a real-world setting, we have to talk about Barthélemy Thimonnier.

By 1830, this French tailor had a machine that used a hooked needle to create a chain stitch. It worked. It worked so well, in fact, that he opened a factory with 80 machines to sew uniforms for the French Army.

He was living the dream. Until the nightmares started.

Local tailors were terrified. They thought this mechanical beast would steal their jobs and leave their families starving. So, they did what people did in 1830s France: they formed a mob. They stormed Thimonnier's factory, smashed every single machine to splinters, and chased him out of town. He nearly died. He eventually tried again, but he never recovered his momentum and died penniless.

Innovation usually comes with a target on its back.

Elias Howe and the "Lockstitch" breakthrough

While Thimonnier was running for his life in France, an American named Elias Howe was tinkering in a basement in Massachusetts.

Howe is the guy who figured out the "lockstitch." This was the game-changer. Instead of just one thread looping through itself (which unraveled easily), Howe used two threads—one from a needle and one from a shuttle underneath. They locked together inside the fabric.

It was genius. It was also a commercial flop.

Howe struggled to find investors. He went to England to try and sell his idea, failed, and came back to the U.S. only to find that sewing machines were suddenly everywhere. People had just... stolen his idea. One of those people was a flamboyant actor and tinkerer named Isaac Merritt Singer.

💡 You might also like: Tyco Romex Splice Kit: Why You Might Never Need an Electrical Box Again

The Great Sewing Machine War

Singer didn't invent the sewing machine. He refined it.

He took Howe's design, added a foot pedal (treadle) so you could use both hands to guide the fabric, and made the needle move up and down instead of side-to-side. It was a much better machine. But he was using Howe's patented lockstitch.

Howe sued. He sued everyone.

The legal battles were so intense they became known as the "Sewing Machine War." It was the first major patent thicket in American history. Eventually, the lawyers realized they were all just making themselves poor, so they formed the Sewing Machine Combination in 1856. This was the first "patent pool." The four major manufacturers agreed to stop suing each other and instead charge every other smaller company a fee to use their tech.

Howe finally got rich. Singer became a household name.

Why the answer still matters today

When you look at who made the first sewing machine, you’re really looking at the blueprint for how modern tech is developed. It’s never one guy. It’s a chain of people stealing, improving, and litigating.

- Wiesenthal (1755): The double-pointed needle.

- Saint (1790): The first actual design (on paper).

- Madersperger (1814): An Austrian who spent his life savings on a machine that didn't quite catch on.

- Thimonnier (1830): The first functional factory-level machine.

- Hunt (1833): Built a lockstitch machine but refused to patent it because he didn't want to put people out of work.

- Howe (1846): The man who finally patented the lockstitch.

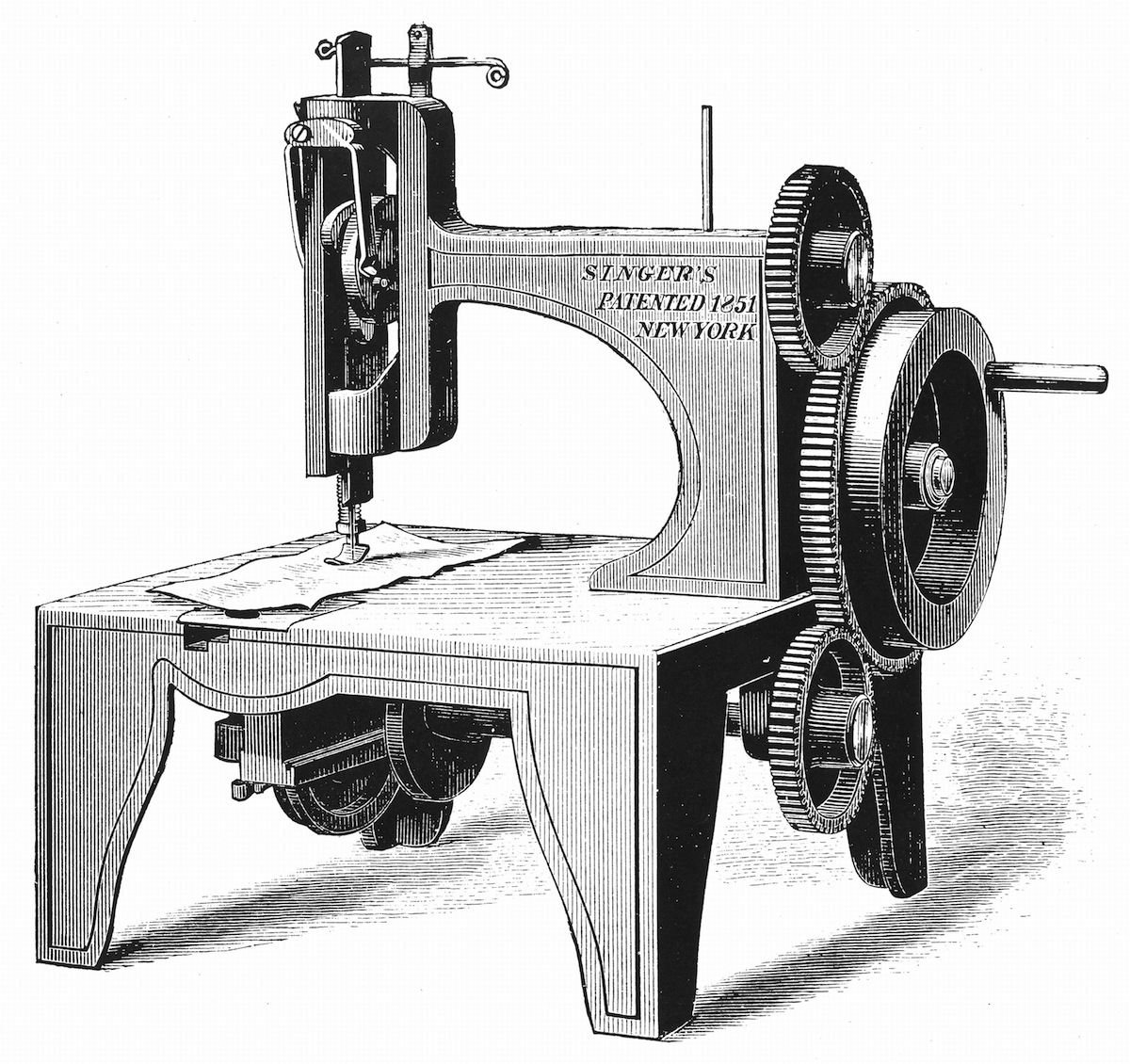

- Singer (1851): The man who made it practical and popular.

Walter Hunt is probably the most interesting character in this whole circus. He was a prolific inventor—he also invented the safety pin—but he had a massive conscience. He saw what happened to Thimonnier and decided that he didn't want to be responsible for thousands of seamstresses losing their livelihoods. He just walked away from the sewing machine.

Can you imagine an inventor doing that today? Just walking away from a billion-dollar idea because of ethics? It's wild to think about.

Practical takeaways for the history-obsessed

If you’re trying to track down the history of a specific vintage machine or you’re writing a paper on industrialization, keep these things in mind. First, look at the patent date, not the manufacture date. Most early machines have a list of patent dates stamped on a brass plate. These represent the "Combination" fees they paid.

Second, understand that "first" is a loaded word. Are you asking who had the first idea? (Saint). Who had the first working machine? (Thimonnier). Or who had the first machine people actually bought? (Singer).

How to identify early sewing machine tech

- Chain stitch machines: Usually have one thread source. If the thread breaks, the whole seam pulls out like a flour sack.

- Transverse shuttles: These machines (like early Howe or Singer models) have a shuttle that moves back and forth like a boat. They are noisy and vibrate like crazy.

- Treadle bases: If it doesn't have a motor and relies on a foot pump, you're looking at 19th-century or early 20th-century tech.

If you find an old machine in an attic, don't immediately assume it's worth a fortune. Millions were made. But if you see the name "Thimonnier" or an original "Howe" with a serial number under 1,000, you’re looking at a piece of history that survived a literal mob.

The sewing machine didn't just change how we make clothes. It changed how we think about intellectual property. It created the first "buy now, pay later" installment plans (thanks, Singer!). It was the first major home appliance.

🔗 Read more: How to change the clock on iPhone when it stops making sense

So, next time you’re hemming a pair of pants or watching a high-speed industrial machine fly at 5,000 stitches per minute, remember Barthélemy Thimonnier. The guy just wanted to sew some coats, and he ended up sparking a revolution that almost cost him his life.

To dig deeper into this, you should check out the Smithsonian Institution's digital archives on the "Sewing Machine Combination." They have the original legal documents from the 1850s that show exactly how these guys carved up the industry. You can also visit the Science Museum in London to see the reconstructed model of Thomas Saint’s 1790 design—it's a clunky, wooden beast, but it’s where the dream started.

Stop looking for a single inventor. Start looking at the collective, messy, and often violent evolution of an idea that shaped the modern world.