If you ask a random person on the street who made the Declaration of Independence, they’ll probably bark "Thomas Jefferson" before you even finish the sentence. They aren't wrong. But they also aren't exactly right. It’s one of those historical facts that we’ve flattened into a postcard version of reality. We picture a guy with a quill, a candle, and a stroke of genius, working in total isolation.

History is rarely that clean.

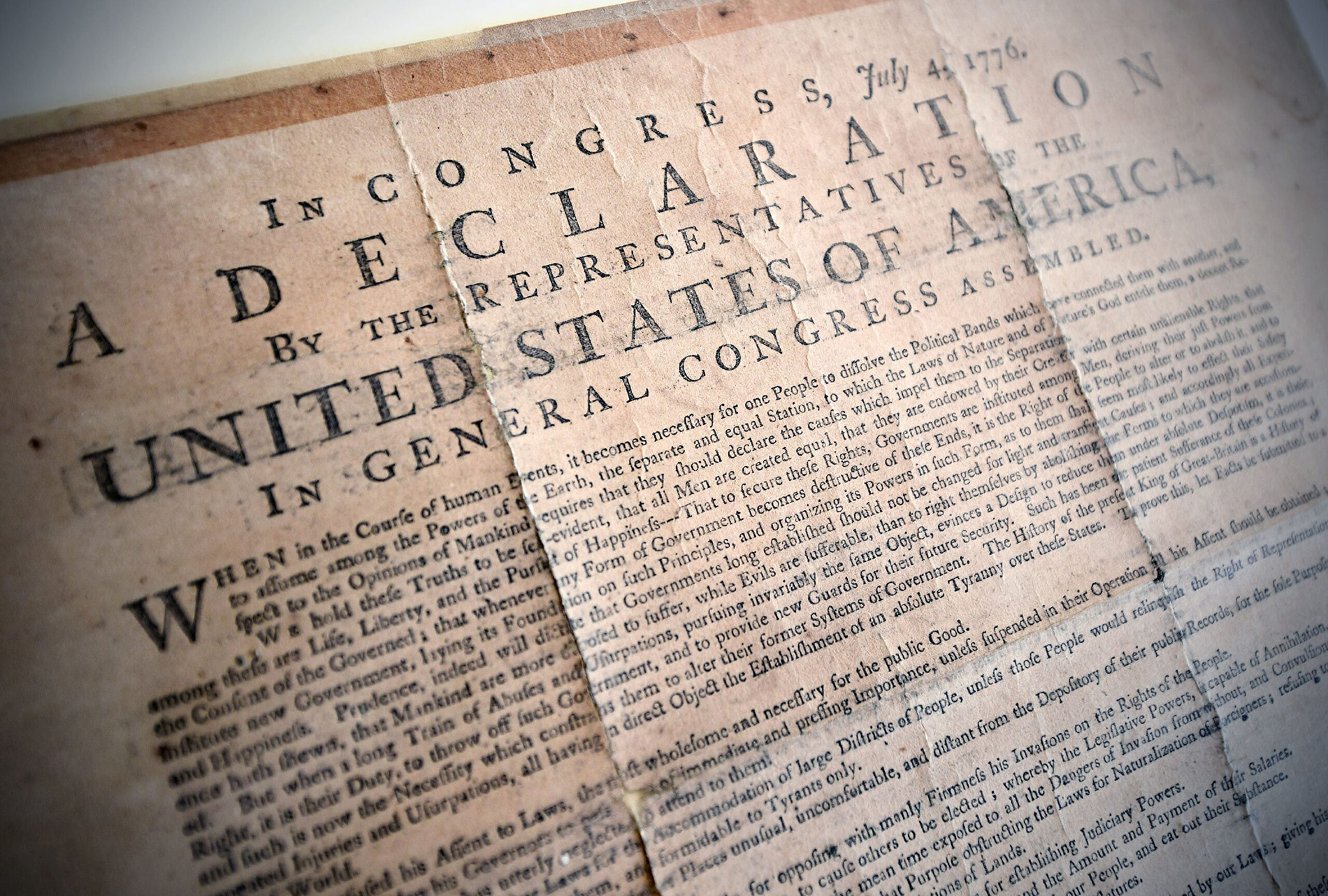

The Declaration wasn't just "made" by one person; it was hauled over the finish line by a committee of five, edited by a room full of grumpy, sweating politicians, and eventually signed by men who knew they were basically signing their own death warrants if the British caught them. It was a group project from hell. You've probably had those in school or at work—the ones where you do the bulk of the heavy lifting and then everyone else starts nitpicking your word choice. That was Jefferson's life in the summer of 1776.

The "Committee of Five" and the Drafting Nightmare

While Jefferson gets the lion's share of the credit, the Continental Congress actually appointed a team. They wanted a diverse group to handle the optics. You had the intellectual powerhouse from Virginia (Jefferson), the blunt pragmatist from Massachusetts (John Adams), the world-famous scientist and diplomat from Pennsylvania (Benjamin Franklin), and two guys who mostly just filled out the roster: Roger Sherman of Connecticut and Robert R. Livingston of New York.

Honestly, Adams was the one who pushed Jefferson to write it. Jefferson tried to get out of it. He wanted Adams to do the dirty work. Adams refused, famously telling Jefferson that he was a much better writer and that a Virginian had to be at the head of the business to keep the Southern colonies on board.

Jefferson spent about 17 days hunkered down in a second-floor rented room at the "Graff House" in Philadelphia. He wasn't looking for original ideas. He wasn't trying to be "inventive." In his own words years later, he said the goal was to provide "an expression of the American mind." He pulled heavily from George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights and the philosophy of John Locke. If you’ve ever felt like you were just rearranging ideas you found on the internet to make a point, Jefferson was right there with you.

Why Franklin and Adams Mattered

Once Jefferson finished his "rough draught," he didn't send it straight to the printers. He took it to Franklin and Adams.

Franklin was the ultimate editor. He was old, he was gouty, and he was brilliant. One of the most famous changes in history came from Franklin's pen. Jefferson had originally written "We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable." Franklin crossed that out. He swapped it for "self-evident."

📖 Related: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

Think about that for a second. "Sacred" implies a religious or mystical requirement to believe. "Self-evident" implies that you’d have to be an idiot not to see it. It shifted the document from a theological argument to a rationalist, Enlightenment-era slam dunk.

The Edits That Almost Broke Jefferson

On July 2, 1776, the Congress voted for independence. That was the actual legal break. But they still had to approve the text of the public announcement.

For the next two days, the Continental Congress tore Jefferson’s draft apart. He sat there in the corner, reportedly seething in silence, while they hacked away at his prose. They made 86 changes. They cut about a quarter of the total text.

The most significant and painful cut? A long, blistering passage where Jefferson blamed King George III for the slave trade. It was a complicated, hypocritical moment—Jefferson himself owned hundreds of enslaved people—but he had included a stinging indictment of the "execrable commerce." The delegates from South Carolina and Georgia weren't having it. They threatened to walk out. To keep the colonies united, the passage was scrubbed.

The Men Who Put Pen to Paper

So, who made the Declaration of Independence official? That would be the 56 signers.

We often think they all signed on July 4. They didn't. Most signed on August 2, 1776. Some signed weeks or even months later. Matthew Thornton of New Hampshire didn't put his name down until November.

The signatures weren't just for show.

👉 See also: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

- John Hancock: The President of the Congress. He signed first and he signed big. He wanted King George to be able to read his name without his spectacles.

- Benjamin Rush: A doctor who later regretted how much the country became polarized.

- Edward Rutledge: The youngest signer at age 26.

- Benjamin Franklin: At 70, he was the oldest, reportedly quipping that they must all hang together or they would most assuredly hang separately.

These weren't just "founding fathers" in wigs. They were lawyers, merchants, and farmers. Some of them lost everything. Carter Braxton of Virginia saw his ships captured and his estate ruined. Richard Stockton of New Jersey was captured by the British and treated so poorly he never truly recovered his health.

The Role of the "Invisible" Makers

There is a side to this story that usually stays in the shadows.

Jefferson was able to write the Declaration because he had the luxury of time and status. That status was built on the labor of enslaved people like Robert Hemings, who accompanied Jefferson to Philadelphia. While Jefferson was upstairs writing about "unalienable rights" and "liberty," Hemings was downstairs tending to his needs.

You also have to look at the printer. John Dunlap.

Once the text was approved on July 4, Dunlap worked through the night in his shop to produce the "Dunlap Broadsides." These were the first printed copies. About 200 were made. They were rushed out to the colonies to be read aloud in town squares and to the troops. If Dunlap hadn't been a fast typesetter, the "declaration" would have stayed a secret in a room in Philadelphia.

And then there's Mary Katharine Goddard.

In 1777, she was the one who printed the first version of the Declaration that actually included all the signers' names. Before that, the names were kept secret to protect them from treason charges. She was a powerhouse publisher in Baltimore and she put her own name at the bottom of the document: "Baltimore, in Maryland: Printed by Mary Katharine Goddard."

✨ Don't miss: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

What Most People Get Wrong About the Declaration

It wasn't a law. It didn't "set up" the government.

Actually, the Declaration is basically a breakup letter. It’s a legal brief. It’s a list of grievances. It was designed to convince the rest of the world—specifically France—that the Americans were serious and deserved military support.

People often confuse it with the Constitution. They aren't the same. The Declaration is the why. The Constitution is the how.

Common Misconceptions:

- It was signed on July 4th: Nope. Only Hancock and Charles Thomson (the secretary) signed the initial printed version that day.

- The original is in the Library of Congress: It's actually in the National Archives in D.C., and it’s fading fast because it was handled so poorly in the 1800s.

- There’s a map on the back: Sorry, National Treasure fans. There is no secret map. There is, however, a small flip-side notation that says "Original Declaration of Independence dated 4th July 1776."

How to Engage With This History Today

Understanding who made the Declaration of Independence changes how you look at American democracy. It wasn't a divine revelation. It was a messy, compromised, edited-by-committee document written by a man who didn't always live up to his own words.

If you want to dive deeper into the reality of 1776, here is what you should actually do:

- Read the "Rough Draught": Look up Jefferson's original version before Congress edited it. It’s angrier, more emotional, and shows exactly what the other delegates were afraid of.

- Visit the Graff House site: If you're ever in Philadelphia, go to the corner of 7th and Market. It’s a reconstruction, but standing in that space makes the writing process feel much more "real" and less like a legend.

- Study the "Dunlap Broadsides": Look at the typography. See how the words were emphasized. It reminds you that this was meant to be heard, not just read silently on a screen.

- Check out the Goddard Broadside: Acknowledge the woman who took the risk of printing the names of the "traitors" when the war was looking very grim for the Americans.

History isn't a statue. It’s a series of choices made by people who were just as stressed and uncertain as we are. When you realize that, the Declaration becomes much more than a piece of parchment. It becomes a living example of how hard it is to actually get everyone on the same page.

The "making" of it didn't end in 1776. Every time the document is used to argue for expanded rights—whether for women in 1848 at Seneca Falls or during the Civil Rights Movement—the Declaration is being "made" all over again.

Actionable Insight: Next time you hear someone credit Jefferson alone, remember the "Committee of Five" and the 86 edits. It serves as a reminder that even the most important ideas usually require a team, a lot of compromise, and a very good editor. To see the signatures for yourself, you can view high-resolution scans at the National Archives.