Ask a dozen people who is the inventor of the first computer and you’ll get a dozen different answers. Some will confidently shout "Charles Babbage!" while others might mention Alan Turing because they saw The Imitation Game. The tech geeks in the back might mutter something about the ENIAC or a guy named Konrad Zuse.

They are all right. And they are all wrong.

The problem isn't that we don't know our history; it’s that we can't agree on what a "computer" actually is. Are we talking about a massive brass machine that never actually worked? Or a room-sized monster that sucked enough power to dim the lights in Philadelphia? Maybe we mean the first thing that looks like the laptop you’re using right now?

Tracing the lineage of computing isn't a straight line. It’s a messy, chaotic web of failed projects, genius-level math, and wartime secrets that stayed hidden for decades.

The Victorian Dreamer: Charles Babbage

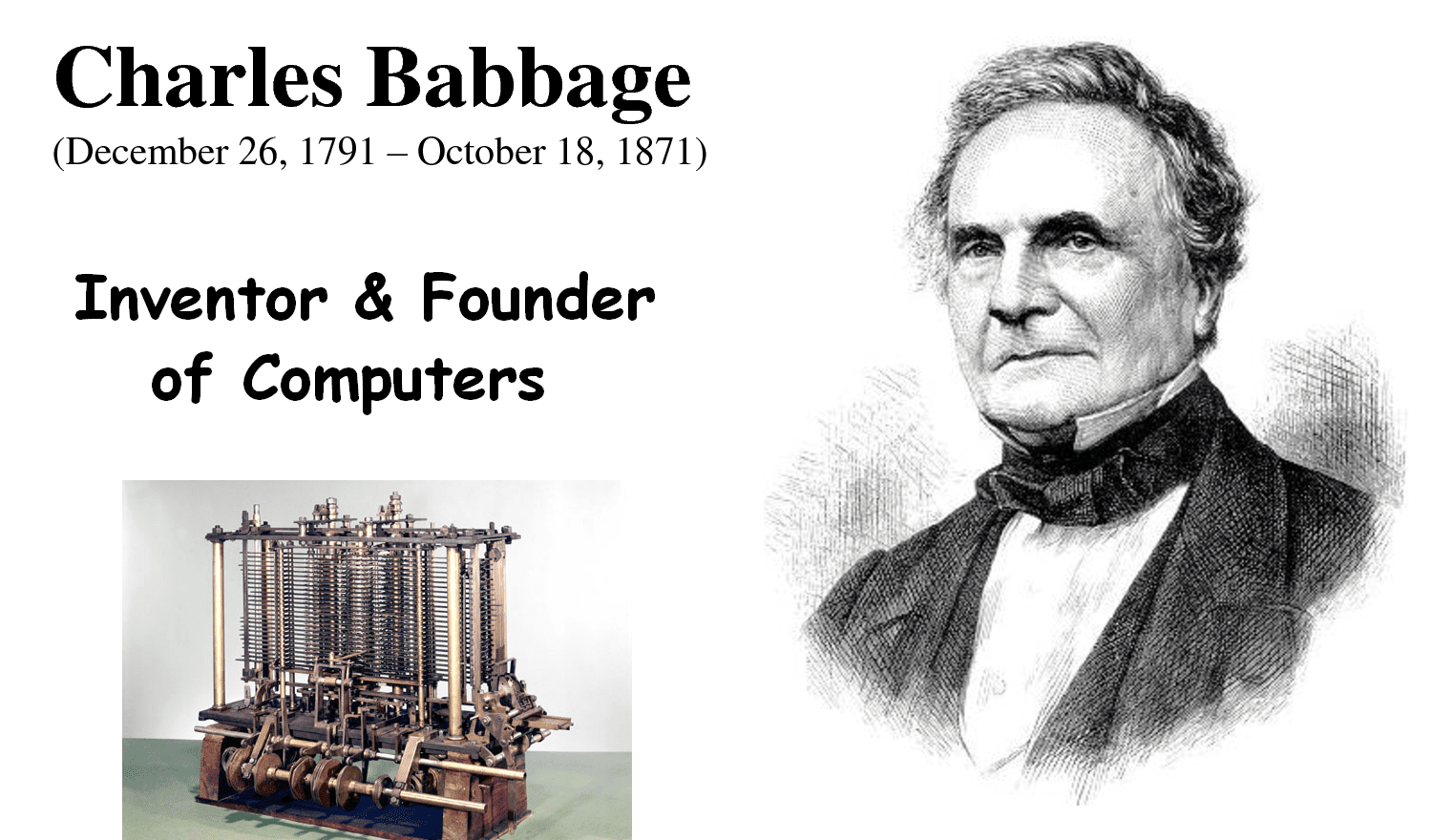

If we are being technical about the design, the search for the inventor of the first computer starts in the 1830s with Charles Babbage. He was a grumpy, brilliant Englishman who hated street musicians and loved logarithms.

Babbage got tired of human "computers"—literally people whose job it was to calculate math tables by hand—making mistakes. He wanted a machine to do it. His first attempt was the Difference Engine, essentially a giant mechanical calculator. But his real masterpiece was the Analytical Engine.

This wasn't just a calculator. It had a "mill" (a CPU), a "store" (memory), and it used punch cards for input. It was Turing-complete before Turing was even born.

The catch? He never finished it.

The British government eventually pulled his funding because he kept changing the design. It was too complex for the manufacturing tech of the era. However, his friend Ada Lovelace saw what he didn't. She wrote an algorithm for the machine, making her the first programmer in history. She realized this thing wasn't just for numbers; it could potentially create music or art if programmed correctly.

The German Engineer Google Almost Forgot

For a long time, the Western world ignored Konrad Zuse. Working in his parents' living room in Berlin during the late 1930s, Zuse built the Z1.

📖 Related: The Big Bang Theory: Why It’s Still the Best Explanation for Everything

It was a mechanical beast, but here’s the kicker: it used binary.

Most people at the time were still obsessed with decimal systems. Zuse realized that "yes/no" or "on/off" logic was the way to go. By 1941, he completed the Z3, which many historians now argue was the first fully functional, programmable, automatic digital computer.

Why didn't we hear about him for years? Because it was Nazi Germany. The Z3 was destroyed in an Allied bombing raid in 1943. Zuse’s work didn't influence the American or British developments because it was locked behind enemy lines. It’s one of those "what if" moments in history. If Zuse had more funding or better materials, the digital age might have started a decade earlier.

The Colossus and the Secret of Bletchley Park

While Zuse was tinkering in Berlin, the British were desperate to crack the German "Lorenz" cipher. Enter Tommy Flowers.

Flowers was a post office engineer, not a high-profile academic. He built Colossus, the world’s first electronic, digital, programmable computer. It used over 1,500 vacuum tubes. It was fast. It worked.

But because the work was part of the Ultra intelligence project at Bletchley Park, it was classified for decades. Winston Churchill supposedly ordered the machines to be broken into pieces no larger than a man's hand after the war.

Because of this secrecy, Flowers never got the credit he deserved during his lifetime. When people asked who is the inventor of the first computer in the 1950s, nobody could say "Tommy Flowers" without going to prison for violating the Official Secrets Act.

ENIAC: The American Giant

In 1945, the Americans unveiled ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer). Built at the University of Pennsylvania by John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert, it was a behemoth.

- It weighed 30 tons.

- It filled a 1,500-square-foot room.

- It used 18,000 vacuum tubes.

- It could do 5,000 additions per second.

For a long time, ENIAC was legally considered the first computer. It was the first "general-purpose" electronic computer that actually functioned and stayed in the public eye. But there was a legal drama that changed everything.

In the 1970s, a massive lawsuit (Honeywell v. Sperry Rand) actually stripped Mauchly and Eckert of their patent. The judge ruled that they had derived their ideas from a quiet professor in Iowa named John Vincent Atanasoff.

Atanasoff and his graduate student, Clifford Berry, had built the ABC (Atanasoff-Berry Computer) in 1942. It wasn't "general purpose"—it could only solve linear equations—but it was the first to use vacuum tubes and binary math together.

The Nuance of "First"

Honestly, choosing one person feels like a slight to everyone else. It’s like asking who invented the car. Do you give it to the guy who drew a cart with an engine, or the guy who actually built the first internal combustion motor?

If you want the "blueprint" guy, it's Charles Babbage.

If you want the "first binary machine" guy, it's Konrad Zuse.

If you want the "first electronic" guy, it's John Vincent Atanasoff.

If you want the "first programmable electronic" guy, it's Tommy Flowers.

If you want the "first commercial success" guys, it's Mauchly and Eckert.

📖 Related: TikTok Ban Explained: Why the App Is Still on Your Phone in 2026

Modern computing is a pile-on of ideas. You’ve got Alan Turing providing the mathematical framework (the Turing Machine), Vannevar Bush working on analog computers, and Grace Hopper later creating the first compilers.

Why This Matters Today

Understanding who is the inventor of the first computer isn't just a trivia game. It shows us how innovation actually works. It's rarely a "eureka" moment in a vacuum. It’s usually a lot of people working on the same problem, hindered by the technology of their time or the secrecy of their governments.

We see the same thing happening now with quantum computing. There isn't one "inventor." There are labs at Google, IBM, and various universities all inching toward the finish line.

Actionable Insights for Tech History Buffs

If you want to dive deeper into this without getting bogged down in boring textbooks, here is how to actually explore the roots of computing:

- Visit the Science Museum in London. They have a working replica of Babbage’s Difference Engine No. 2. Seeing those gears move in person makes you realize how insane his vision was for the 1800s.

- Read "The Innovators" by Walter Isaacson. It’s probably the best narrative breakdown of how Lovelace, Babbage, and the ENIAC team connected.

- Watch the TNM (The National Museum of Computing) videos. They are based at Bletchley Park and have reconstructed the Colossus. Watching those vacuum tubes glow is a religious experience for techies.

- Check out the Computer History Museum's online archives. They have the original documents from the Honeywell v. Sperry Rand case that finally gave Atanasoff his credit.

The story of the computer is a story of persistence. Most of these inventors died broke or unrecognized. They were building for a future they could see, even if their contemporaries just saw a pile of expensive junk. Next time you pull a smartphone out of your pocket, remember it’s not just a piece of tech; it’s the end result of a 200-year-old argument between geniuses.