Everyone knows the name. Neil Armstrong. It’s one of those facts burned into the collective consciousness of the human race, right up there with the shape of the Earth or the color of the sky. But when people ask who is the first man to land on the moon, they often skip over the messy, terrifying, and borderline miraculous technicalities that actually put him there. It wasn’t just a stroll out of a door. It was a frantic race against a fuel gauge hitting zero while hovering over a boulder-strewn crater in a spacecraft that had the structural integrity of a soda can.

Neil Armstrong wasn’t just a pilot; he was a quiet, almost reclusive engineer who happened to have ice water in his veins. You’ve probably seen the grainy black-and-white footage a thousand times. But the context matters. In July 1969, the world was a powder keg of Cold War tension, and the United States was betting its entire global reputation on a three-stage Saturn V rocket that was essentially a controlled explosion.

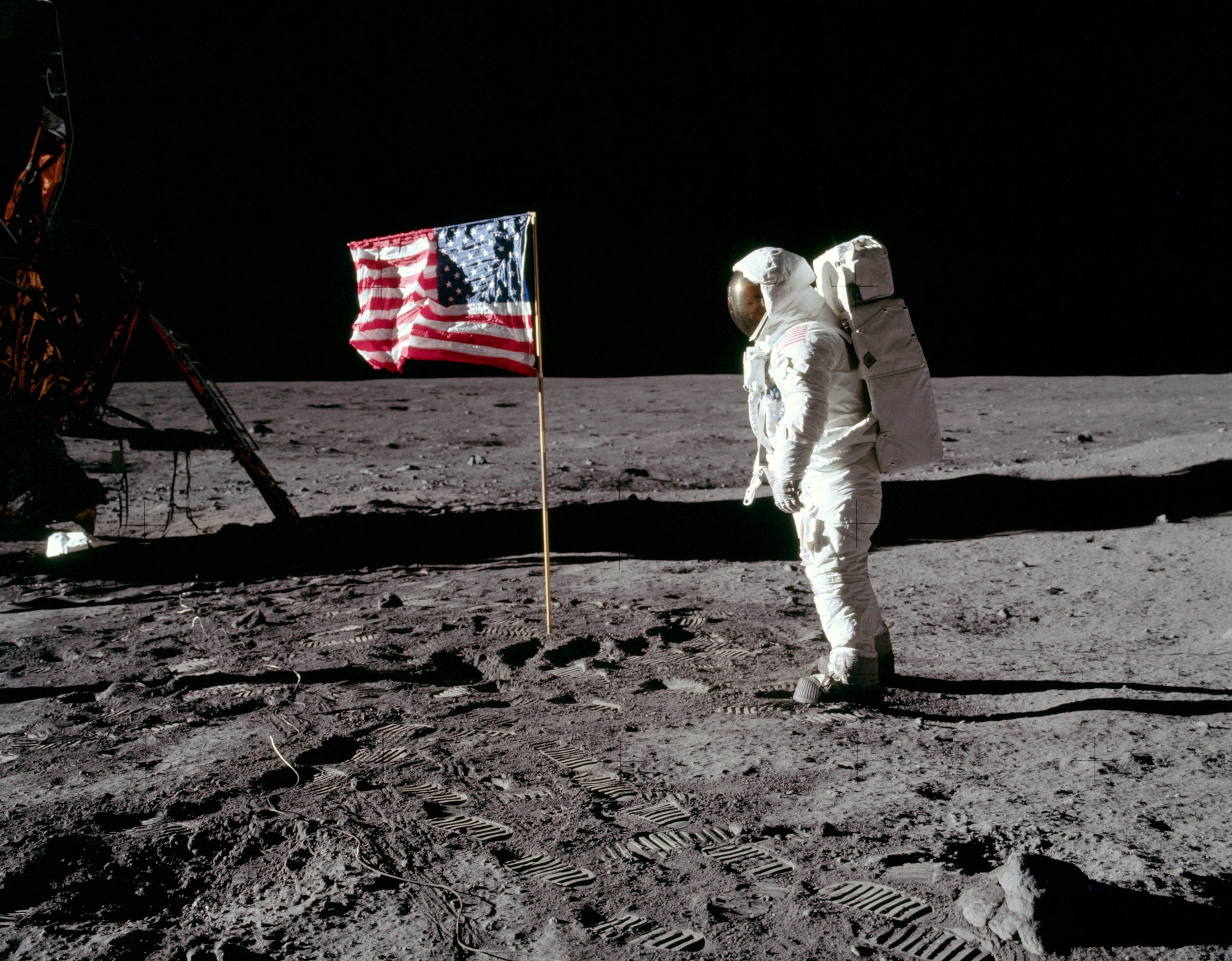

The Man Behind the Visor

Neil Alden Armstrong. Born in Wapakoneta, Ohio. He wasn't some bravado-heavy cowboy like some of the other Mercury or Gemini astronauts. He was a "white socks and pocket protector" kind of guy who just happened to be world-class at flying experimental planes. Before NASA, he flew the X-15, a rocket plane that touched the edge of space. He was used to things going wrong.

Actually, things went wrong a lot.

During the Gemini 8 mission, a thruster got stuck open. The spacecraft started spinning at one revolution per second. Most people would have blacked out and died. Armstrong figured out how to shut down the main system and use the reentry thrusters to stop the tumble. He was calm. That’s why Deke Slayton, the man who chose the crews, wanted him for the big one.

The decision of who is the first man to land on the moon wasn't purely about skill, though. There was a lot of internal politics. Buzz Aldrin, the Lunar Module pilot, was technically "next in line" to step out based on how previous spacewalks worked. But the physical layout of the Eagle (the Lunar Module) meant the commander—Armstrong—was sitting closer to the door. Trying to have Aldrin climb over Armstrong in a pressurized suit would have been like trying to do a yoga pose inside a refrigerator. Plus, NASA leadership felt Armstrong's ego-free personality was better suited for the eternal fame that would follow.

The Descent: 60 Seconds of Fuel Left

The landing was a nightmare.

📖 Related: Apple Lightning Cable to USB C: Why It Is Still Kicking and Which One You Actually Need

As the Eagle descended toward the lunar surface, the onboard computer started screaming. "1202 Alarm." "1201 Alarm." These were executive overflow errors. Basically, the computer was being asked to do too much at once because a radar switch was in the wrong position. Armstrong didn't panic. He kept his eyes on the window.

He realized the computer was guiding them straight into a "boulder field"—a massive crater filled with car-sized rocks. If they landed there, the ship would tip over. They’d be stuck forever. Armstrong took manual control. He tilted the lander forward to "hop" over the crater, searching for a flat spot.

Back at Mission Control in Houston, Charlie Duke (the CAPCOM) was listening to the fuel counts. "60 seconds," he called out. Then "30 seconds." If they hit zero before touchdown, they would have had to abort or crash.

"Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed."

They had about 25 seconds of fuel left. Total silence followed for a few beats before Houston breathed again.

One Small Step and a Massive Misquote

When we talk about who is the first man to land on the moon, we always quote the line: "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind."

👉 See also: iPhone 16 Pro Natural Titanium: What the Reviewers Missed About This Finish

Armstrong always insisted he said "one small step for a man." Without the "a," the sentence doesn't actually make grammatical sense because "man" and "mankind" mean the same thing in that context. Interestingly, acoustic analysis of the tapes years later suggests he might have actually said it, but the "a" was lost in a burst of static. Or maybe he just forgot it in the heat of the moment. Who could blame him? He was standing on a dead world 238,000 miles from home.

Why It Wasn't Just Neil

It feels weird to talk about the "first man" without mentioning that he wasn't alone. Buzz Aldrin joined him on the surface about 20 minutes later. While Armstrong was the philosopher-engineer, Aldrin was the "Dr. Rendezvous"—the guy who literally wrote the book on how to link up spaceships in orbit.

And then there was Michael Collins.

Collins is the "forgotten" man of Apollo 11. He stayed in the Command Module, Columbia, orbiting the moon by himself. Every time he went behind the far side of the moon, he was the loneliest human being in history. No radio contact with Earth. No contact with his friends on the surface. Just him and the stars. If Neil and Buzz couldn't get the Eagle off the surface, Collins would have had to fly back to Earth alone, leaving them there to die. That was the grim reality they all accepted.

The Technology of 1969 vs. Today

It’s a cliché, but your smartphone has millions of times more processing power than the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC). The AGC ran at about 0.043 MHz. It had 72KB of memory. Much of the software was literally hand-woven by women in a factory—they called it "LOL memory" (Little Old Lady memory) because they wove wires through magnetic cores to create the 1s and 0s.

It was primitive, yet it worked. It worked because it was built with a philosophy of "redundancy." Everything had a backup. And if the backup failed, you had a pilot like Armstrong who could fly the thing by the seat of his pants.

✨ Don't miss: Heavy Aircraft Integrated Avionics: Why the Cockpit is Becoming a Giant Smartphone

The Impact: Was it Worth It?

People argue about the cost. It was roughly $25 billion at the time (over $150 billion today). But the "spinoffs" changed everything.

- Integrated Circuits: NASA’s demand for tiny computers accelerated the silicon chip revolution.

- Water Purification: The tech used to clean water for the crew is now used in systems globally.

- Fireproof Fabrics: After the tragic Apollo 1 fire, NASA developed materials that are now standard for firefighters.

Beyond the gadgets, it changed how we saw ourselves. The "Blue Marble" photo—though actually taken by the Apollo 17 crew later—started the modern environmental movement. Seeing Earth as a tiny, fragile Christmas ornament in a vast black void made the wars and borders of 1969 look pretty stupid.

Common Misconceptions About the Landing

We have to address the "hoax" stuff because it still clutters up the search results. No, the flag wasn't "waving" in the wind. It was hanging from a horizontal telescopic rod that didn't fully extend, creating a wrinkled look that looked like motion in a still photo. No, there are no stars in the photos because the moon's surface is incredibly bright; you have to set the camera's shutter speed fast, which cuts out the faint light of distant stars.

The best evidence we went? The 842 pounds of moon rocks brought back. These rocks are geologically distinct from Earth rocks—they have no water trapped in the crystal structure and are pitted with tiny "zap pits" from micrometeorite impacts that can't happen on a planet with an atmosphere.

What You Can Do Next

If you want to go deeper into the life of the man who answered the question of who is the first man to land on the moon, don't just watch the movies. Check out these specific resources for the real, unvarnished history:

- Read "First Man" by James R. Hansen. It is the only authorized biography of Neil Armstrong. It goes way deeper than the movie into his psychological state and his career as a test pilot.

- Visit the NASA Image Archives. They’ve uploaded high-resolution scans of the original Hasselblad photos. You can see the reflection in the visors and the texture of the lunar dust in incredible detail.

- Listen to the Apollo 11 Flight Journal. NASA has transcripts and audio of the entire mission. Hearing the banter between the astronauts and the dry, professional tone of Mission Control during a life-or-death crisis is fascinating.

- Track the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO). You can actually see photos taken in the last few years from a satellite orbiting the moon. It shows the descent stages of the Apollo landers still sitting there, along with the "footpaths" made by the astronauts.

Neil Armstrong died in 2012, but his footprint is still there. Because there is no wind on the moon, that print will likely stay there for millions of years. He wasn't just a man landing on a rock; he was the first representative of our species to touch another world. That’s a legacy that doesn't need any embellishment.