New York City in the 1860s was a mess. Absolute chaos. Muddy streets, horses dying in the gutters, and thousands of immigrants pouring off ships every single week with nowhere to go. If you were a poor Irish laborer arriving at Castle Garden, you didn't look to the government for help because the government didn't care about you. You looked for the man with the diamond stud in his shirt and a cigar in his mouth. You looked for William Magear Tweed.

To understand who is Boss Tweed, you have to stop thinking of him as just a "corrupt politician." That’s too simple. He was essentially the unofficial CEO of New York City at a time when the city was becoming the most important economic engine on the planet. He wasn't just stealing; he was building, or at least pretending to.

The Rise of the Tiger

Tweed wasn't born into greatness. He was a chair maker. A fireman. In those days, volunteer fire departments were basically street gangs with engines. They fought each other more than they fought fires. Tweed climbed the ranks of the "Americus Engine Company Number 6"—the Big Six—whose symbol was a snarling Bengal tiger. That tiger eventually became the symbol of Tammany Hall, the political machine Tweed would use to hijack the city’s treasury.

He was a big man. 300 pounds. He had this magnetic, back-slapping energy that made people feel like he was on their side. By the late 1860s, he sat at the center of the "Tweed Ring," a tight-knit group of four men: Tweed himself, City Chamberlain Peter "Brains" Sweeny, Comptroller Richard "Slippery Dick" Connolly, and Mayor A. Oakey Hall, who was mostly there to look fancy and sign papers.

Together, they owned the city.

How the Money Actually Disappeared

People always ask how they got away with it. Honestly, it was brilliantly boring. They didn't rob banks at gunpoint. They used invoices.

Take the New York County Courthouse. It’s still there on Chambers Street. They started building it in 1861 with a budget of $250,000. By the time they were "done," the city had spent nearly $13 million. For a single building. To put that in perspective, the United States bought Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million around the same time. Tweed’s courthouse cost almost double the price of Alaska.

How? The "Triple Invoice."

📖 Related: Fire in Idyllwild California: What Most People Get Wrong

If a carpenter did $500 worth of work, the Ring told him to bill the city $5,000. The city paid the $5,000. The carpenter kept his $500 plus a little "hush money" bonus, and the rest went straight into the pockets of the Tweed Ring. One plasterer, a guy named Andrew Garvey, supposedly earned $133,000 in two days. That’s roughly $3 million today for two days of spreading plaster. You can see why they called him the "Prince of Plasterers."

The audacity was the point. They weren't hiding; they were flaunting it. Tweed lived in a mansion on Fifth Avenue. He owned a massive estate in Greenwich, Connecticut. He was the third-largest landowner in New York City history.

The Immigrant Connection

You can't talk about who is Boss Tweed without talking about the people who voted for him.

The "respectable" reformers of the era—the wealthy elites—despised the poor. Tweed didn't. He gave them jobs. He gave them coal in the winter and turkeys at Christmas. If a family got evicted, Tweed’s men found them a place to stay. He greased the wheels of naturalization, turning immigrants into citizens (and voters) faster than the law allowed.

It was a cynical trade. He gave them survival; they gave him power.

But it worked. While the "Good Government" types were writing op-eds about civic virtue, Tweed was on the docks shaking hands. He understood that a hungry person doesn't care about a balanced budget; they care about a warm meal. This is the nuance people miss. Tweed was a predator, but he was a predator who provided a social safety net that the actual government refused to build.

The Men Who Took Him Down

Every villain needs a foil. For Tweed, it was two very different men: Thomas Nast and George Jones.

👉 See also: Who Is More Likely to Win the Election 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

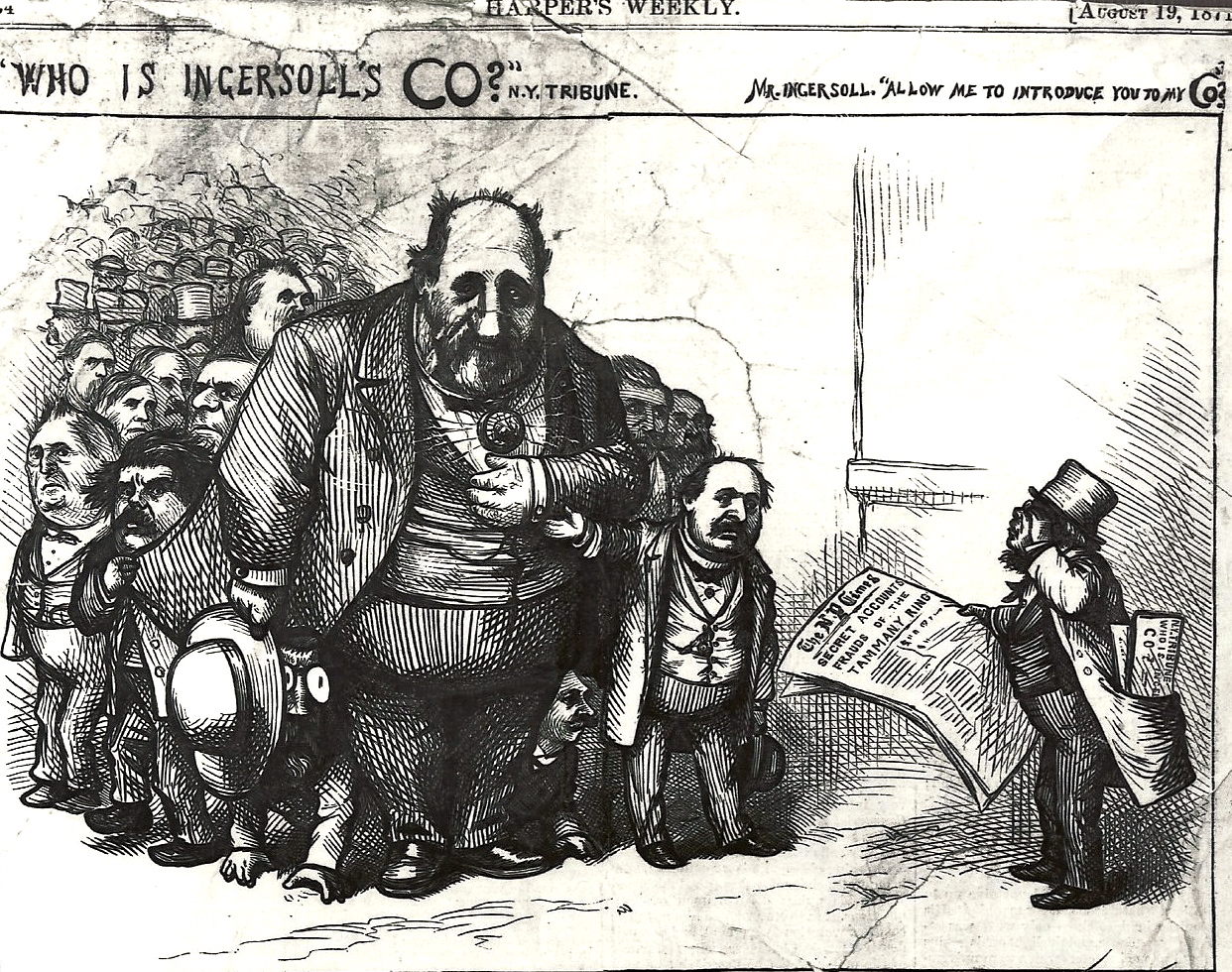

Nast was a cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly. He didn't just draw funny pictures; he created the modern political cartoon. He gave us the Republican Elephant and the Democratic Donkey. He also gave Tweed nightmares. Tweed famously said, "I don't care a straw for your newspaper articles; my constituents don't know how to read, but they can't help seeing them damn pictures!"

Nast drew Tweed as a bloated vulture, as a man with a money bag for a head, as a giant crushing the tiny citizens of New York. It was visceral. It was effective.

Then there was George Jones, the owner of The New York Times.

In 1871, a disgruntled former employee of the Ring leaked the "Secret Accounts" to the Times. The Ring tried to bribe Jones with $5 million to keep the story quiet. Think about that. $5 million in 1871. Jones could have retired as one of the richest men in America. Instead, he told them to pound sand and published the evidence.

The Final Act and the Great Escape

The end was messy.

Tweed was arrested, tried, and eventually sent to jail. But he was Boss Tweed. He convinced his jailers to let him go on "home visits." During one of these visits, he simply walked out the back door and vanished.

He fled to Florida, then Cuba, and finally Spain. He was working as a common seaman on a Spanish ship when he was recognized. How? By a Thomas Nast cartoon. Spanish authorities saw a drawing of Tweed kidnapping two children (a metaphor for his corruption) and thought he was an actual child kidnapper. They arrested him and sent him back to New York on a warship.

✨ Don't miss: Air Pollution Index Delhi: What Most People Get Wrong

He died in the Ludlow Street Jail in 1878.

The sad irony? He died in a jail that he had authorized the construction of when he was in power. He even checked the "comforts" of the cells during its building. I guess he was planning ahead, even if he didn't know it.

Why We Should Still Care

The story of who is Boss Tweed isn't just a history lesson. It’s a blueprint for how systems fail.

Corruption doesn't usually look like a movie villain. It looks like a guy offering you a job when you're desperate. It looks like a complicated invoice that nobody bothers to double-check. It looks like "it’s just the way things are done."

Tweed’s legacy is everywhere. He helped professionalize the police force (while making them his personal army). He pushed through the development of the Upper West Side. He was a founding trustee of the Brooklyn Bridge. He was a builder and a destroyer all at once.

Lessons from the Tweed Era

If you want to apply the "Tweed Test" to modern politics or business, look for these three red flags:

- The Lack of Transparency in Infrastructure: When the cost of a subway line or a bridge triples without a clear explanation, look at the contractors. History says they might be "plasterers."

- The Weaponization of the Vulnerable: Beware of leaders who provide "favors" to the poor while stealing from the public treasury that should be funding their schools and hospitals.

- The "Too Big to Fail" Ego: Tweed genuinely believed he was the only person who could make New York work. That level of narcissism is usually followed by a massive bill.

To really get a feel for this era, you should visit the Tweed Courthouse behind New York City Hall. Look at the marble. Look at the craftsmanship. It is a stunning, beautiful monument to the most massive theft in American history. It’s a reminder that even the most corrupt systems can leave behind something that looks like progress.

Next Steps for History Buffs:

If you're in Manhattan, walk through the lobby of the Tweed Courthouse (70 Chambers St) to see where the money went. For a deeper dive, track down a copy of "The Shame of the Cities" by Lincoln Steffens or "Boss Tweed's New York" by Seymour J. Mandelbaum. These texts go beyond the cartoons and explain the actual mechanics of 19th-century political machines. Stay skeptical of anyone who says they can "fix everything" if you just give them total control of the checkbook.