Ever sat at a red light for three minutes straight, staring at a chip of peeling paint on your dashboard, and wondered exactly who to blame for this delay? Most of us think it was one guy. One genius inventor who just woke up and decided the world needed a three-colored pole. But history is rarely that clean. If you're looking for a single name to pin on the question of who invented traffic lights, you're actually looking for a handful of people—a Victorian engineer, a self-taught African American inventor, and a guy from Salt Lake City who probably just wanted to get home for dinner.

The truth is, traffic control wasn't born out of a desire for order. It was born out of blood and horse manure. By the mid-1800s, cities like London and New York were absolute death traps. Pedestrians were constantly getting flattened by horse-drawn carriages. The "rules of the road" were basically just whoever had the biggest horse or the loudest shout.

The explosive start in Victorian London

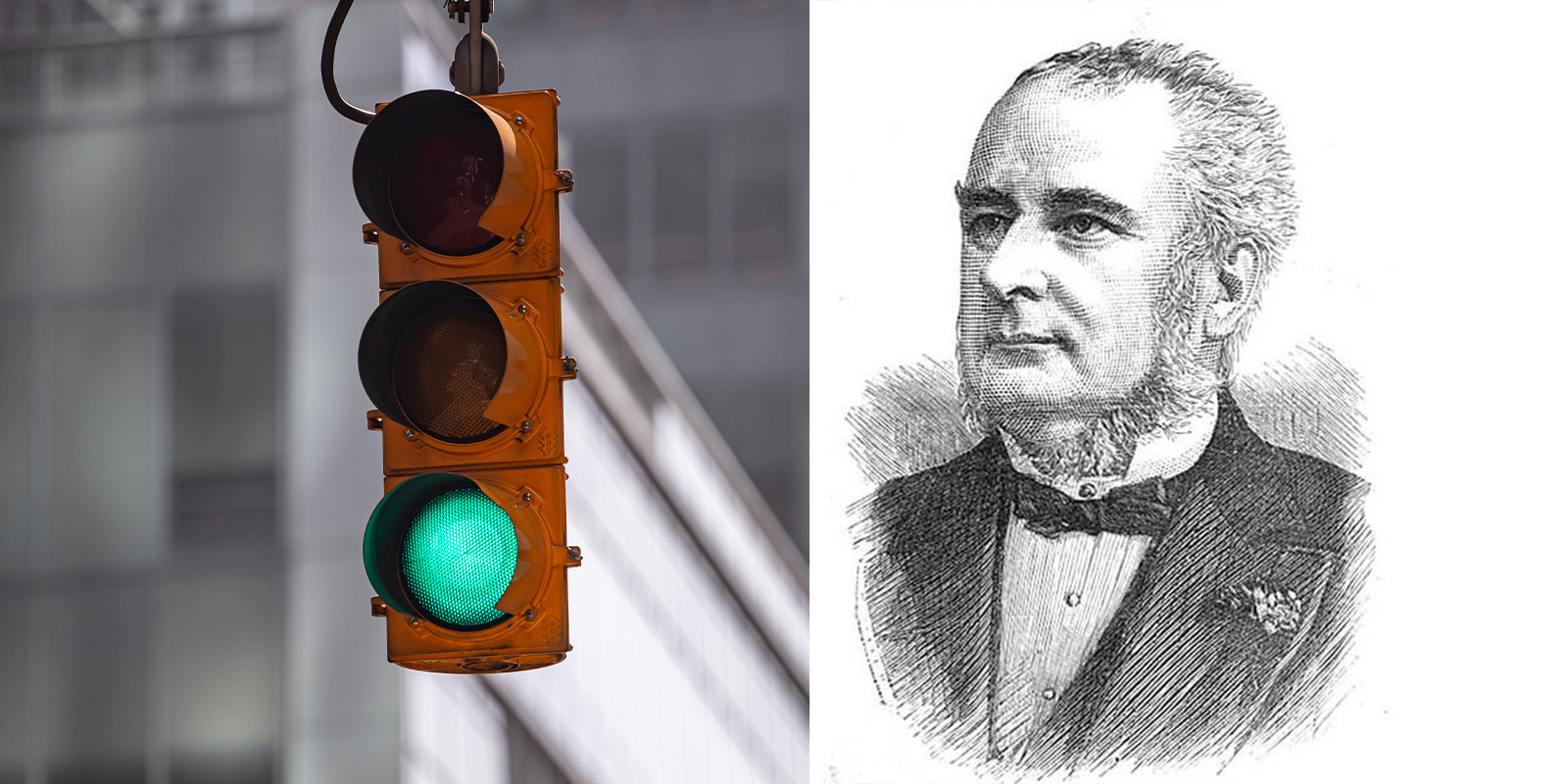

It all kicked off in 1868. That's way before cars were even a thing. J.P. Knight, a railway signaling engineer, decided to take what worked for trains and stick it on a street corner outside the Houses of Parliament.

Knight's contraption was a "semaphore" system. It had big wooden arms that would flip out horizontally to say "Stop" and at an angle to say "Caution." At night, because you couldn't see wood in the dark, they used red and green gas lamps.

It worked. Sort of. For about a month, everything was great until a gas leak caused the whole thing to explode in a policeman's face. The poor guy was badly injured, and London basically said, "Nope, not doing that again." It took nearly fifty years for the world to try automated traffic lights again.

Garrett Morgan and the "All-Stop" revolution

Fast forward to 1923. Cars are everywhere now. The Model T is cheap, and Cleveland, Ohio is a chaotic mess of bicycles, horses, pedestrians, and fast-moving automobiles. Garrett Morgan, an incredibly prolific inventor who also created an early version of the gas mask, witnessed a horrific crash between a carriage and an automobile.

Before Morgan, most signals were just "Stop" and "Go." There was no "Yellow." You can imagine the chaos. One second you're cruising, the next second the sign flips and the guy behind you is in your backseat.

👉 See also: Frontier Mail Powered by Yahoo: Why Your Login Just Changed

Morgan’s patent was for a T-shaped pole that had a third position: a "halt" for all directions. This meant pedestrians could actually cross the street without fearing for their lives. Honestly, it was a game-changer. He eventually sold the rights to General Electric for $40,000, which was a massive sum back then. While he didn't invent the "first" light, his focus on the interval between stop and go is what saved thousands of lives.

The electric shift in America

Wait, what about the lights we actually recognize? The red-yellow-green electric ones?

A lot of credit goes to Lester Wire, a policeman in Salt Lake City. In 1912, he basically took a wooden birdhouse, stuck some colored bulbs in it, and wired it to the overhead trolley lines. It looked DIY because it was. He didn't even bother to patent it, which is why his name often gets left out of the history books.

Then there was William Potts. In 1920, Potts, a Detroit police officer, decided that two colors weren't enough. He was the first one to use the three-color system (red, amber, green) and he figured out how to make it work at a four-way intersection using a single switch.

Why the colors?

You ever wonder why red means stop? It’s not just because it looks like blood. It’s because red has the longest wavelength in the visible spectrum. That means it doesn't scatter as easily as other colors, so you can see it from a much further distance, even through fog or rain.

- Red: Longest wavelength, most visible.

- Green: Originally, in early railway history, green actually meant "caution" and white meant "go." That caused a lot of deaths when red lenses fell out and engineers thought a white light meant the track was clear. Eventually, they swapped green to "go."

- Yellow: The middle ground. It’s high-contrast and easy to see at a glance.

The modern era: AI and sensors

We’ve come a long way from exploding gas lamps. Today, who invented traffic lights is a question that is being answered by software engineers.

✨ Don't miss: Why Did Google Call My S25 Ultra an S22? The Real Reason Your New Phone Looks Old Online

Most lights aren't on simple timers anymore. If you've ever felt like the light "saw" you coming, it’s because it did. Inductive loop sensors—those rectangles you see cut into the asphalt—detect the metal in your car. Many cities are now moving toward AI-driven systems that use cameras and machine learning to adjust light timing in real-time based on traffic flow.

It’s about "Green Waves." If you time it right, you can hit ten green lights in a row. That’s not luck; that’s an algorithm doing exactly what J.P. Knight was trying to do with a wooden arm in 1868.

What most people get wrong about traffic light history

There’s this weird urge to find one "father" of the traffic light. We love a simple story. But if you look at the patents, it’s a mosaic.

- James Hoge (1914): Installed the first electric signal in Cleveland. It had "STOP" and "MOVE" signs and a loud buzzer that sounded before the light changed. Imagine how annoying that would be today.

- The "First" claim: London had the first signal, Salt Lake City had the first electric light, and Detroit had the first three-color light.

- Automatic vs. Manual: For a long time, these things were hand-cranked or operated by a guy in a "crow's nest" tower in the middle of the street.

It wasn't until the late 1920s that we started seeing fully automatic timers that didn't require a human to sit there and flip a switch all day.

How to use this knowledge today

Knowing the history of the traffic light is cool for trivia, but it actually helps you navigate the modern world if you understand how the tech works under your tires.

Look for the sensors

If you’re a motorcyclist or a cyclist, you’ve probably sat at a light that won't turn. That’s because the inductive loop (the wire buried in the road) isn't sensing enough metal. Try to stop directly over the "cut" lines in the pavement. That’s where the magnetic field is strongest.

🔗 Read more: Brain Machine Interface: What Most People Get Wrong About Merging With Computers

Respect the "Yellow"

Garrett Morgan didn't fight for the "all-clear" signal just so we could floor it. In most states, the yellow light duration is calculated based on the speed limit. It’s usually 1 second for every 10 mph. If you're doing 40 mph, you typically have 4 seconds of yellow.

Watch for the "Opticom"

If you see a small white light on top of a traffic signal suddenly start blinking, an emergency vehicle is approaching. The "Opticom" system uses infrared to tell the light to turn green for the ambulance or fire truck. Don't try to race it.

The traffic light is one of those pieces of technology that is so ubiquitous we forget it's there until it breaks. It’s a 150-year-old conversation between engineers, police officers, and inventors all trying to solve the same problem: how do we get from point A to point B without hitting each other?

Next time you’re stuck at a red, think of J.P. Knight and his exploding gas lamp. It could be a lot worse.

Actionable Insights for Modern Drivers:

- Positioning matters: Always stop your front tires behind the white line but ahead of the asphalt "seams" to ensure the sensor detects your vehicle.

- Audit your local lights: If a light seems "broken" or the timing is off, most city websites have a "Report a Problem" section. These sensors fail often, and the city usually won't fix them unless someone says something.

- Understand the "Sneak": In many jurisdictions, you can legally complete a left turn after the light turns red if you were already established in the intersection. Check your local laws, but Garrett Morgan’s "all-stop" philosophy is what allows this to happen safely.