You probably used one this morning without thinking. It’s that tiny, rhythmic zzzzzt sound as you close your jacket or secure your jeans. We call it a zipper, but for decades, it was the "clasp locker" or the "hookless fastener," and honestly, it was a total disaster for a long time. If you’re looking for a single name to answer who invented the zip fastener, you’re going to be disappointed because it wasn't a "eureka" moment in a shed. It was a slow, agonizing evolution involving a sewing machine pioneer, a guy who hated tying his shoes, and a Swedish-American engineer who finally made the damn thing work.

It’s one of those inventions that seems so simple you’d assume it’s been around forever. It hasn't. It took nearly eighty years of patents, bankruptcies, and public ridicule before the world stopped using buttons for everything.

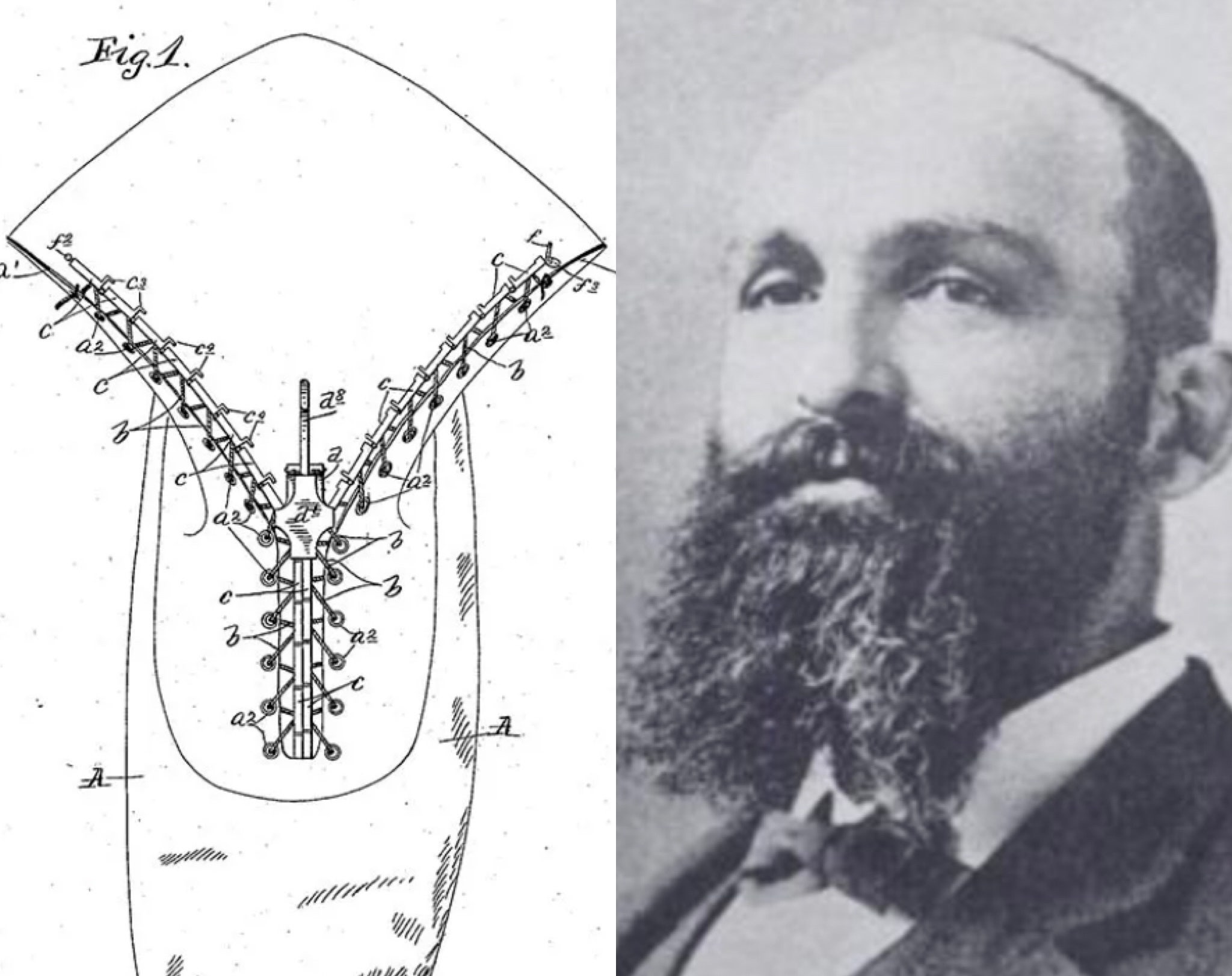

The Man Who Almost Had It: Elias Howe

Before we get to the modern zipper, we have to talk about Elias Howe. Yeah, the sewing machine guy. In 1851, Howe received a patent for an "Automatic, Continuous Clothing Closure." It was basically a series of hooks and eyes joined by a slider.

It sucked.

Howe was so busy defending his sewing machine patents and fighting off legal rivals that he never really marketed his fastener. It was clunky. It caught on fabric. It was, for all intents and purposes, a scientific curiosity rather than a piece of hardware. He had the right idea—using a slider to join two sides of fabric—but the execution was miles off. He missed his chance to change the world’s closets because he was too busy in court.

Whitcomb Judson and the "Clasp Locker"

The real momentum started with a guy named Whitcomb Judson. Imagine being an inventor in Chicago in the 1890s. Everything is changing, but you’re still bending over every morning to lace up high-top boots with twenty different eyelets. Judson was tired of it. He wanted a "clasp locker" that could be closed with one hand.

In 1893, he debuted his invention at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. People were obsessed with the Ferris Wheel and the lightbulbs, but Judson’s fastener? It was a flop.

📖 Related: Installing a Push Button Start Kit: What You Need to Know Before Tearing Your Dash Apart

His design used a complicated arrangement of hooks and latches. It didn't look like a modern zipper; it looked like a tiny, angry metal centipede. It had a nasty habit of popping open at the worst possible times. Imagine walking down a street in 1894 and having your entire boot fly open because a metal tooth got slightly bent. That’s why nobody bought them.

Judson did, however, start the Universal Fastener Company. They struggled. They moved to Pennsylvania. They almost went broke. But they had one thing going for them: they hired Gideon Sundback.

Gideon Sundback: The Man Who Actually Won

If you have to name one person for who invented the zip fastener as we know it, it’s Gideon Sundback.

Sundback was a Swedish-American electrical engineer who had a very personal stake in the company; he married the plant manager’s daughter, Elvira Aronson. When Elvira died young, Sundback threw himself into his work to cope with the grief. This period of intense, mourning-fueled engineering between 1906 and 1913 changed everything.

He realized the "hook and eye" approach was the problem. It was too bulky. Instead, he moved to a "hookless" system based on interlocking teeth.

His 1913 "Hookless Fastener No. 1" was better, but his 1914 "Hookless No. 2" was the masterpiece. This is the modern zipper. It used small, scooped teeth that nested into each other. He also increased the number of elements per inch. Instead of a few big hooks, he used dozens of tiny teeth. This made the closure secure, flexible, and—most importantly—it didn't pop open when you sat down.

👉 See also: Maya How to Mirror: What Most People Get Wrong

Why We Call it a "Zipper" Anyway

For a long time, these things were just called "separable fasteners." That is a terrible name. No one wants to buy a "separable fastener."

The name "Zipper" actually came from the B.F. Goodrich Company in 1923. They decided to put Sundback’s fastener on a new type of rubber boots. Legend has it that an executive liked the "zip" sound it made when he pulled the slider up. He called the boots "Zippers," and the name stuck to the fastener itself, much to the annoyance of the Hookless Fastener Company (which later became Talon, Inc.).

The Big Break: Tobacco Pouches and Kids' Clothes

You’d think the fashion world would have jumped on this immediately. They didn't. High-end tailors thought zippers were "cheap" or "mechanical."

The first real success wasn't on pants. It was on tobacco pouches. Men liked the way it kept their tobacco fresh and was easy to open with cold fingers. Then came the U.S. Navy. During World War I, the Navy used zippers on flight suits and life vests.

But the real revolution happened in children's clothing.

In the 1930s, marketers started pushing zippers as a way for children to dress themselves. "Teach your children self-reliance!" the ads screamed. If a toddler could zip up their own coat, that was one less chore for mom. This "self-help" angle for kids' clothes gave the zipper a foothold in the home that it never lost.

✨ Don't miss: Why the iPhone 7 Red iPhone 7 Special Edition Still Hits Different Today

The Battle of the Fly: 1937

The final frontier was the men’s trouser fly. For centuries, buttons reigned supreme. In 1937, French fashion designers finally started featuring zippers in men’s trousers. Esquire magazine famously called the zipper the "newest tailoring idea for men." They bragged that it would eliminate the "possibility of unintentional and embarrassing disarray."

Basically, they told men that zippers would stop their buttons from popping open in public. It worked. Within a few years, the button fly was a vintage relic, and the zipper was the global standard.

Surprising Facts About Zipper History

- The YKK Mystery: Have you ever looked at your zipper and seen "YKK"? That stands for Yoshida Kogyo Kabushikikaisha. Founded by Tadao Yoshida in 1934, this Japanese company now produces roughly half of the world's zippers. They succeeded not by inventing the zipper, but by perfecting the manufacturing of it.

- The NASA Connection: Standard zippers aren't airtight. For space suits, engineers had to develop pressure-sealing zippers that use rubber gaskets to prevent oxygen from leaking out into the vacuum of space.

- The "Forbidden" Fastener: In the early 20th century, some religious groups actually spoke out against the zipper because they felt it made clothes too easy to take off, which they associated with "loose morals."

How to Tell if a Zipper is Quality (and How to Fix It)

Since you’re now an expert on Sundback’s legacy, you should know how to maintain it. Most people think a stuck zipper is dead. It usually isn't.

- The Graphite Trick: If a slider is sticky, rub a No. 2 pencil on the teeth. The graphite acts as a dry lubricant. It works better than oil, which just attracts dirt.

- The Pliers Fix: If the zipper teeth don't stay closed after the slider passes, the slider itself has likely stretched out. Take a pair of needle-nose pliers and gently squeeze the "mouth" of the slider to tighten its grip on the teeth.

- Look for Brass: If you're buying heavy-duty gear, look for brass or nickel-silver teeth rather than plastic (nylon). Metal zippers have a higher "lateral strength," meaning they can handle being stuffed into a suitcase better than plastic ones.

Practical Next Steps for the Curious

If you want to see the evolution of the zip fastener for yourself, keep an eye out for "Talon" brand zippers at vintage clothing stores. These are the direct descendants of Sundback's original company. Comparing a 1940s Talon zipper to a modern YKK one shows just how little the core technology has changed in a hundred years.

You can also look up the original patent drawings for U.S. Patent No. 1,219,881. Seeing Sundback’s hand-drawn diagrams makes you realize just how much math went into making those tiny teeth nest together perfectly.

The zipper isn't just a fastener. It's a miracle of precision engineering that survived eighty years of failure before it finally conquered the world.

Source References:

- The Evolution of Useful Things by Henry Petroski.

- U.S. Patent Office Archives: Gideon Sundback, 1917.

- Smithsonian Institution: History of the Zipper.