Ever sat at a red light in a rush and wondered who to blame for the delay? It’s a simple question with a messy, complicated answer. Most folks think there’s just one name behind it. They’re wrong.

Basically, the story of who invented the traffic signal isn’t a straight line from Point A to Point B. It’s more like a chaotic four-way intersection before the lights were installed. You have a Victorian-era gas explosion, a self-taught Black inventor in Cleveland, and a guy in Salt Lake City who just wanted to protect his fellow police officers.

It wasn’t one "Eureka!" moment. It was a decades-long scramble to stop people from dying in the streets.

The London Disaster of 1868

Before cars were even a thing, London had a massive problem with horse-drawn carriages and pedestrians. It was a mess. Knight’sbridge and Westminster were essentially death traps. Enter John Peake Knight. He was a railway signaling engineer who thought, "Hey, if it works for trains, why not carriages?"

In December 1868, he put up a 20-foot tall pillar near the Houses of Parliament. It had semaphore arms that moved up and down. At night, it used red and green gas lamps.

It worked. For a few weeks.

Then it exploded.

🔗 Read more: Why Browns Ferry Nuclear Station is Still the Workhorse of the South

A gas leak caused the whole thing to blow up, seriously injuring the policeman operating it. London decided that maybe manual traffic control wasn't so bad after all. They wouldn't touch a mechanical signal again for nearly fifty years. This is why when people ask who invented the traffic signal, Knight is often a footnote—he had the right idea, but the technology was literally a ticking time bomb.

The American Gridlock and Lester Wire

Fast forward to the early 1900s. Henry Ford’s Model T is everywhere. Suddenly, you’ve got horses, bicycles, pedestrians, and fast-moving "horseless carriages" all fighting for the same inch of asphalt. It was pure gore. Statistics from the era are actually terrifying; kids playing in the streets were getting mowed down at staggering rates.

Lester Wire, a detective in Salt Lake City, saw the carnage and got fed up. In 1912, he built a birdhouse-looking wooden box. It had two circles dipped in red and green paint. He used electricity from the overhead trolley lines to power it.

Wire never patented it.

He was a cop, not a businessman. He just wanted to stop the accidents. Because he didn't file the paperwork, he often gets left out of the history books, even though his "birdhouse" was arguably the first electric traffic light in the world. People actually mocked him for it. They’d stand at the corner and whistle or make fun of the "flashing coop."

James Hoge and the Cleveland Connection

Two years after Wire’s experiment, a man named James Hoge installed a system in Cleveland, Ohio. This happened on August 5, 1914, at the corner of East 105th Street and Euclid Avenue. This is the date many historians cite as the "birth" of the modern traffic signal.

💡 You might also like: Why Amazon Checkout Not Working Today Is Driving Everyone Crazy

Hoge’s system was different because it was wired so that the police and fire departments could change the lights in case of an emergency. It used words—"MOVE" and "STOP"—instead of just colors. It was efficient. It was controlled. It was also incredibly loud because it featured a buzzer that sounded before the lights changed. Imagine every red light today screaming at you before it flipped. You’d lose your mind.

Garrett Morgan: The Patent that Changed Everything

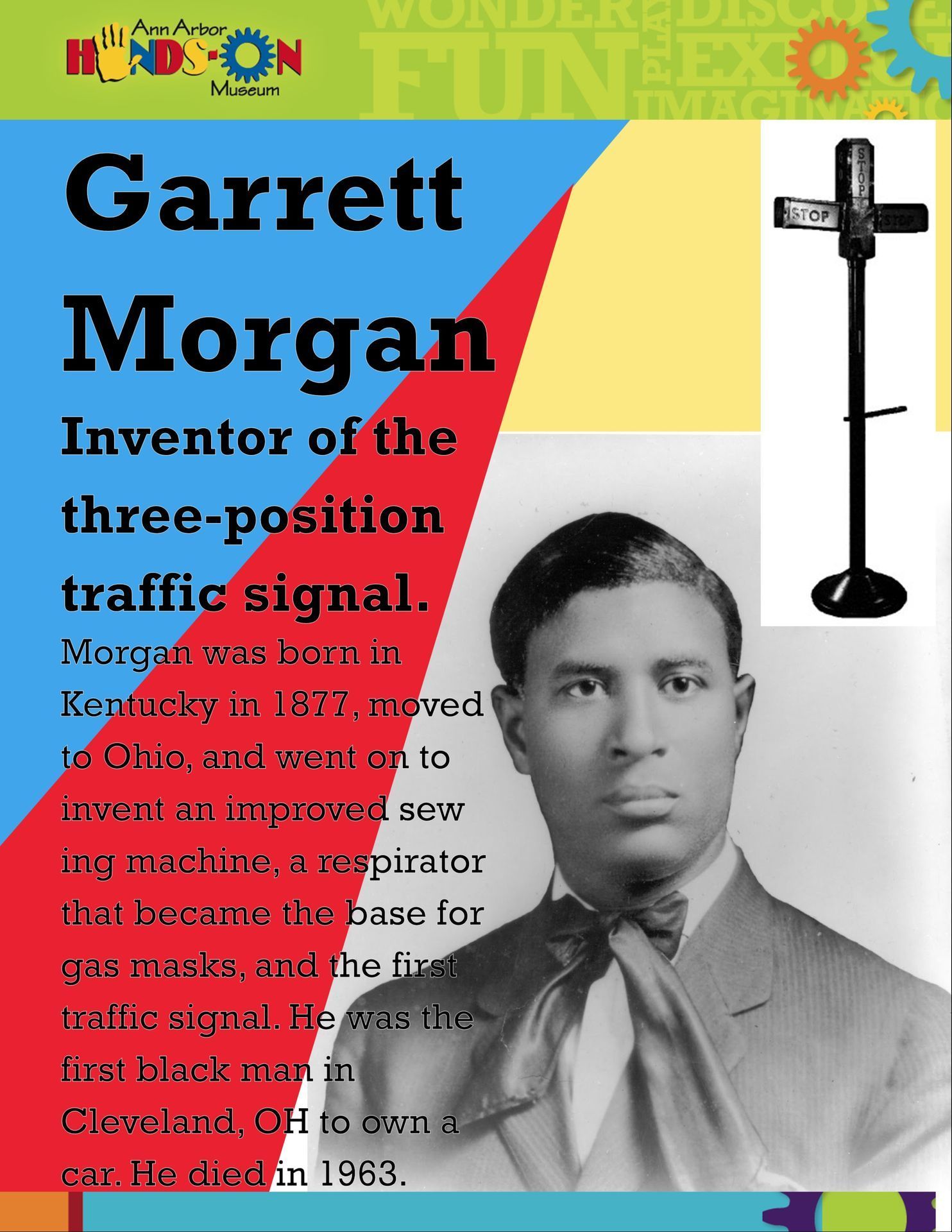

Now we get to the name most people recognize from school: Garrett Morgan. Morgan was a brilliant Black inventor and a total polymath. He’d already made a fortune with a hair-straightening cream and invented a "safety hood" (an early gas mask) that he famously used to rescue workers trapped in a tunnel under Lake Erie.

Morgan’s contribution wasn't about being the first to use electricity. It was about the "yellow."

Before Morgan, lights were basically "Go" or "Stop." There was no warning. Drivers would slam on their brakes or fly through the intersection as the light changed, leading to T-bone collisions. Morgan witnessed a horrific carriage-car accident and realized the system was missing a neutral position.

In 1923, he patented a T-shaped signal that featured a third state. This "caution" phase allowed everyone to clear the intersection before the other side started moving. He eventually sold the patent to General Electric for $40,000—a massive sum in the 1920s.

Why the "First" is so Hard to Pin Down

History is rarely clean. If you're looking for who invented the traffic signal, you have to decide what counts.

📖 Related: What Cloaking Actually Is and Why Google Still Hates It

- John Peake Knight (1868): First to use semaphore and gas lights. (Ended in fire).

- Lester Wire (1912): First electric signal. (Never patented).

- William Potts (1920): A Detroit police officer who actually added the yellow light first, but because he was a municipal employee, he couldn't patent it.

- Garrett Morgan (1923): First to patent a three-position signal, which is the direct ancestor of what we use now.

Most historians give the crown to Morgan because his patent was the one that standardized the industry. Without a patent, an invention is just a local curiosity. Morgan's design was a global solution.

The Evolution of the Bulb

It’s worth noting that the lights we see today don't look much like Morgan’s T-bar. We moved to the "Red-Yellow-Green" vertical stack because it was easier to see from a distance. By the 1930s, the "Green Wave" started appearing in cities like New York, where lights were timed so a driver going the speed limit could hit every green light in a row.

Honestly, we take it for granted now. We look at our phones (don't do that) or change the radio station while waiting for the sensor to trigger the change. But for the pioneers like Wire and Morgan, this was life-or-death engineering.

Modern Tech: The Smart Signal

Today, the "inventor" is essentially an algorithm. We’ve moved past simple timers. Most intersections now use inductive-loop sensors—those circles you see cut into the pavement—which detect the metal in your car through an electromagnetic field.

In some cities, AI cameras are replacing those loops, analyzing traffic flow in real-time to reduce idling. We are literally living in the future Garrett Morgan imagined, where the goal isn't just to stop cars, but to manage the "pulse" of a city.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you're a history buff or just someone who likes knowing how things work, here is how you can apply this knowledge:

- Check the Pavement: Next time you're at a light, look for the rectangular or circular "scars" in the asphalt. Those are the sensors. If you stop too far back, you might not trigger the light.

- Support Minority Inventors: Research more on Garrett Morgan. His story is a masterclass in how Black excellence shaped American infrastructure despite the Jim Crow era.

- Understand the "Yellow": The yellow light isn't a "speed up" signal. It is mathematically timed based on the speed limit of the road—a calculation known as the "Dilemma Zone." Respect it.

- Visit the History: If you’re ever in Dearborn, Michigan, the Henry Ford Museum has one of the original 1920s-era traffic signals. Seeing it in person makes you realize how huge and imposing these early machines were.

The traffic signal wasn't born from a single genius. It was a messy, iterative process born out of blood and broken axles. From Knight’s exploding gas lamp to Morgan’s life-saving patent, it’s a story of human ingenuity trying to keep up with its own fast-moving inventions.