James Hargreaves. That’s the name you usually see in the history books when you look up who invented the spinning jenny. It’s one of those facts we’re forced to memorize in middle school, right along with Eli Whitney and the cotton gin. But history is rarely as tidy as a textbook makes it out to be. Honestly, the story of this wooden machine is less about a "eureka" moment and more about a desperate struggle to keep up with a changing world. It was 1764, or maybe 1765—records from the 18th century are notoriously fuzzy—in a tiny village called Stanhill in Lancashire, England. Hargreaves was a weaver. He was also a carpenter. He was basically a guy who saw a problem and hacked together a solution using the tools he had in his shed.

The problem was simple. Weaving was getting too fast for the spinners.

Before the spinning jenny, you had the flying shuttle, invented by John Kay. This made weaving fabric much quicker. Suddenly, weavers were sitting around waiting for yarn. It took about six to eight spinners just to keep one weaver busy. It was a bottleneck. Hargreaves needed a way to make more thread at once. Legend says he got the idea when his daughter, Jenny, knocked over their single-thread spinning wheel. As it lay on the floor, the spindle kept spinning vertically. Hargreaves realized he could line up a bunch of vertical spindles and spin them all with one wheel. Is that story true? Probably not. Most historians, like those at the British Museum, suspect "Jenny" was just a slang term for "engine" or "gin."

Why the Spinning Jenny Changed Everything

It’s hard to overstate how much this weird wooden frame messed with the status quo. Before Hargreaves, spinning was a one-thread-at-a-time job. It was slow. It was domestic. Women did it at home. The spinning jenny allowed one person to spin eight threads at once. Later versions? They could do eighty. Think about that jump.

It wasn't just a technical upgrade; it was an economic explosion. It moved production out of the casual "I'll do this while the stew cooks" phase and into the "we need a dedicated space for this" phase. But it wasn't perfect. The jenny produced thread that was a bit weak. It was great for "weft"—the yarn that goes across the fabric—but it couldn't handle the "warp," the longitudinal threads that need to be under high tension. For that, you still needed the old ways or, eventually, Richard Arkwright’s water frame.

The Backlash Was Violent

People hated it. Not the consumers, obviously, but the neighbors. Imagine you’ve spent your whole life earning a living spinning yarn, and suddenly your neighbor James builds a machine that does the work of eight people. You'd be terrified. You'd be angry. In 1768, a mob of local spinners broke into Hargreaves' house. They didn't just yell; they smashed his machines to pieces. They saw the spinning jenny as a direct threat to their survival.

🔗 Read more: Calculating Age From DOB: Why Your Math Is Probably Wrong

Hargreaves fled. He moved to Nottingham. He set up a mill, but because he had sold a few machines early on to help pay the bills, he couldn't get a patent that actually stuck. He was technically the man who invented the spinning jenny, but he died in 1778 without ever becoming the wealthy "Captain of Industry" we associate with the Industrial Revolution. He was middle class at best.

The Thomas Highs Controversy

Now, here is where it gets messy. There is a persistent claim that James Hargreaves didn't actually come up with the idea. Some historians point to a reed-maker named Thomas Highs. The story goes that Highs invented a multi-spindle machine a year or two before Hargreaves and named it after his own daughter (who actually was named Jane).

Did Hargreaves steal it? Or did two guys in the same region, facing the same economic pressure, just happen to land on the same mechanical solution? Simultaneous invention happens all the time. Look at the lightbulb or the telephone. However, because Highs didn't have the resources to patent or promote his version effectively, Hargreaves got the credit in the history books. It’s a classic case of the person who commercializes the idea winning the legacy, even if they weren't the "first" to think of it.

Mechanical Specs: How it Actually Worked

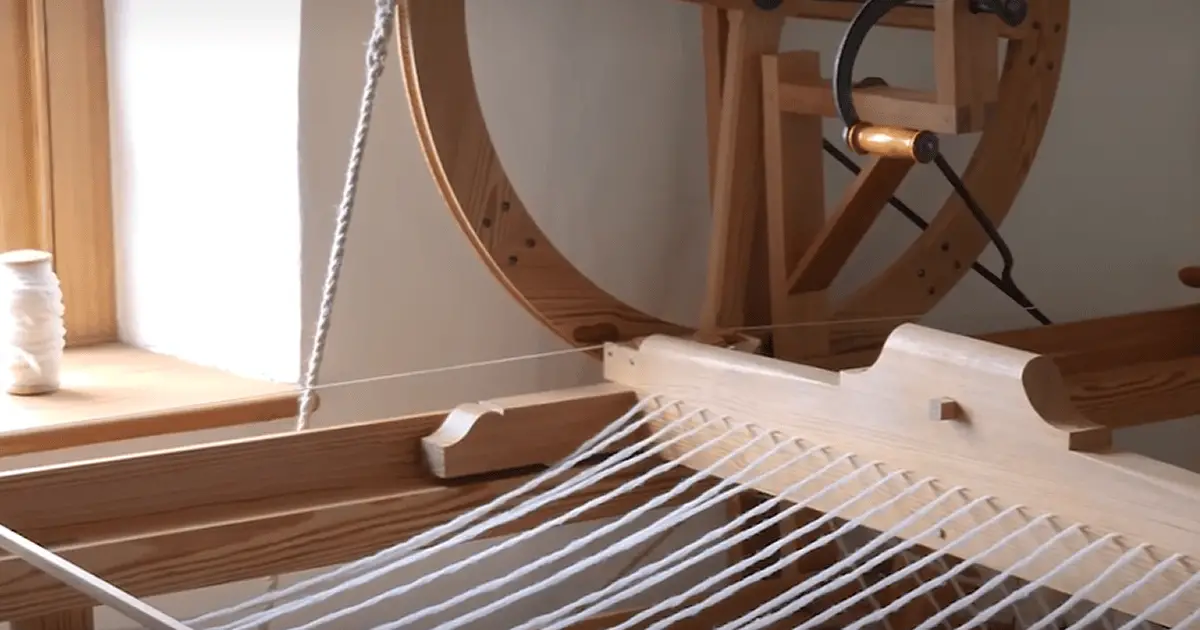

If you saw a spinning jenny today, it would look like a confusing mess of pulleys and wooden pegs. It’s a far cry from the sleek steel machines of the 1900s. Basically, the operator would turn a large wheel with their right hand, which spun all the spindles simultaneously. With their left hand, they moved a carriage back and forth to draw out the fibers and give them the necessary twist.

- Spindle count: Started at 8, eventually reached 80+.

- Power source: Human muscle. No steam, no water (yet).

- Material: Almost entirely wood and iron.

- Thread quality: Soft, slightly irregular, best for cotton or wool weft.

The machine was small enough to fit in a cottage. This is a key detail. It didn't require a factory next to a river. It was the "prosumer" tech of 1765. It allowed families to ramp up production without leaving their homes. This period is what historians call "proto-industrialization." It’s the bridge between the medieval world and the modern one.

💡 You might also like: Installing a Push Button Start Kit: What You Need to Know Before Tearing Your Dash Apart

The Legacy of the Jenny

Eventually, the spinning jenny was outclassed. Samuel Crompton took Hargreaves’ jenny and Arkwright’s water frame and smashed them together to create the "Spinning Mule." The Mule was the final boss of spinning technology. It produced thread that was both strong and fine. By the time the 1780s rolled around, the original jenny was looking a bit like a flip phone in the age of the iPhone.

But we remember Hargreaves because he was the first to break the "one thread" barrier. He proved that human hands didn't have to be the limiting factor in textile production. He paved the way for the factory system, even if he was ultimately a victim of it.

What You Can Learn from Hargreaves Today

If you’re looking at this from a business or tech perspective, the story of who invented the spinning jenny is a masterclass in timing and the dangers of the "First Mover." Hargreaves had the right idea at the right time, but he lacked the legal protection and the scale to truly dominate.

If you want to understand the Industrial Revolution, you have to look at the jenny as the spark. It wasn't the biggest fire, but it was the one that started the blaze. It changed the price of clothing, the nature of work, and the very structure of the English family.

Actionable Insights and Next Steps

To truly grasp the impact of this invention beyond just a name and a date, consider these steps:

📖 Related: Maya How to Mirror: What Most People Get Wrong

Research the "Luddite" movement. Hargreaves wasn't the only one whose machines were smashed. Understanding the 1768 riots helps explain modern fears about AI and automation. History repeats itself, just with different tools.

Visit a textile museum. If you're ever in the UK, the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester has working replicas. Seeing how much physical effort it took to turn that wheel changes your perspective on "handmade" goods.

Compare the Jenny to the Water Frame. Look into Richard Arkwright. He’s the guy who took the "spinning" concept and turned it into a factory empire. It’s a great study in the difference between an inventor and an entrepreneur.

Study the patent failure. Hargreaves lost his legal battle because he sold the machines before filing for protection. If you’re an innovator today, let that be a 250-year-old warning: keep your prototypes secret until your IP is locked down.