If you ask a trivia nut who invented the gasoline engine, they’ll probably bark "Nikolaus Otto" before you can even finish the sentence. Or maybe they'll get fancy and mention Karl Benz. They aren't wrong, exactly. But they aren't totally right either. History loves a clean narrative with a single hero, but the birth of the internal combustion engine was more like a decades-long bar fight involving German engineers, French tinkerers, and a lot of exploding cylinders.

Honestly, the "invention" of the gasoline engine wasn't a single "Eureka!" moment. It was a slow, oily crawl.

The guy who got there first (sorta)

Long before we had gas stations on every corner, people were obsessed with replacing the steam engine. Steam was heavy. It was dangerous. You had to lug around a giant boiler just to get a little bit of movement. In the mid-1800s, engineers were looking for something "internal." They wanted the explosion to happen inside the machine.

👉 See also: How to Use a Conversion Calculator Decimals to Fractions Without Losing Your Mind

Enter Étienne Lenoir.

In 1860, this Belgian-born engineer actually built the first commercially successful internal combustion engine. It didn't run on gasoline, though. It ran on illuminating gas—the stuff people used for streetlights. It was loud, it was inefficient, and it tended to overheat so badly it could basically weld itself shut. But it worked. It proved that you could harness a miniature explosion to turn a shaft. Without Lenoir, the question of who invented the gasoline engine might have a very different answer today.

Nikolaus Otto and the "Four-Stroke" breakthrough

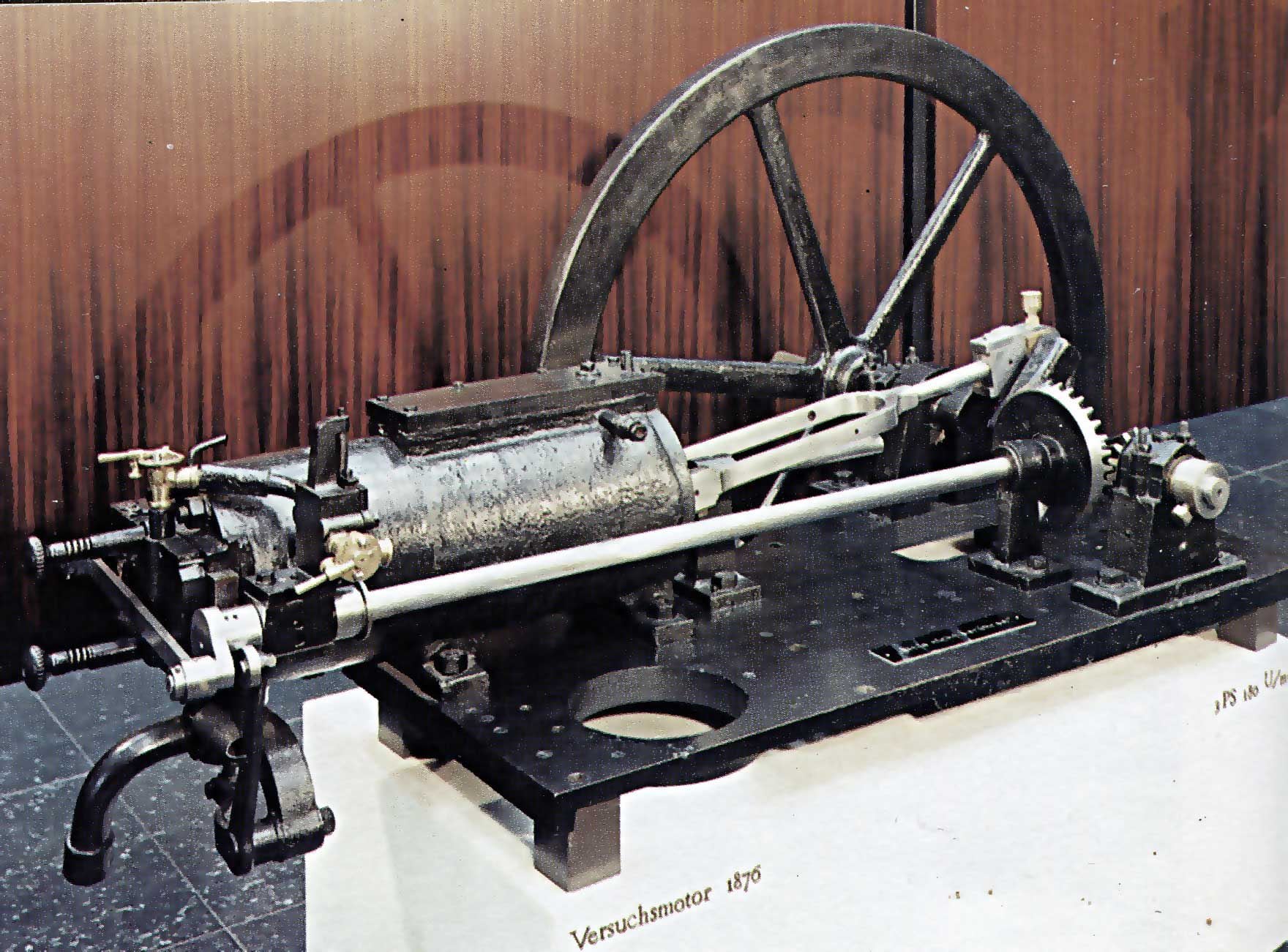

The real turning point happened in 1876. Nikolaus Otto, a traveling salesman turned self-taught engineer, cracked the code. He realized that if you compressed the fuel-air mixture before you ignited it, you got a way bigger bang for your buck. This is the Otto Cycle.

- Intake (sucking in the mix)

- Compression (squishing it)

- Power (the boom)

- Exhaust (getting rid of the smoke)

$P \Delta V$ work was never the same after this.

Otto’s engine was a beast. It was quiet-ish and reliable. But here is the kicker: it was still a stationary engine. It was bolted to factory floors. It was too big and too heavy to put in a carriage. And most importantly, it still wasn't using gasoline as we know it. It was using gas.

Making it mobile: The gasoline pivot

This is where the story gets spicy. Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach—two guys who worked for Otto—decided they wanted to go mobile. They realized that to make an engine small enough for a vehicle, they needed a liquid fuel that was energy-dense.

Gasoline was actually a byproduct of kerosene production back then. It was basically seen as a dangerous waste product. People used it to clean grease off tools or just burned it off as trash. Daimler and Maybach looked at this "trash" and saw gold.

In 1885, they created the "Grandfather Clock" engine. It was small, it ran on gasoline, and they shoved it onto a wooden bicycle. Boom. The first motorcycle. A year later, Karl Benz—working independently—patented the Motorwagen.

📖 Related: Why the As Seen On TV Television Antenna Still Sells (and What It Actually Does)

While Otto gave us the cycle, Benz gave us the car. He integrated the engine into a chassis designed specifically for it, rather than just slapping a motor on a horse carriage. If you’re looking for who invented the gasoline engine in the context of the modern world, Benz is the guy who made it a reality for the masses. Well, the wealthy masses, at least.

The patent wars and the "stolen" idea

History is written by the winners, and Otto almost lost. In the 1880s, his patents were challenged. It turns out a French engineer named Alphonse Beau de Rochas had actually come up with the theory of the four-stroke cycle years before Otto built it. He just never built a working model.

Otto lost his patent rights in Germany. This opened the floodgates. Suddenly, everyone could build four-stroke engines without paying Otto a dime. This is why the late 1800s saw an explosion (literally) of car companies. It’s kinda wild to think that the entire automotive industry exists because of a legal loophole and a forgotten French patent.

Why does this matter now?

We’re currently living through the end of the internal combustion era. With EVs taking over, the gasoline engine is starting to look like the steam engine looked to Nikolaus Otto—bulky, complex, and a bit outdated.

But you can't deny the engineering genius. To take a liquid made of ancient decomposed plankton, spray it into a metal tube, squish it to a fraction of its size, and light it on fire 3,000 times a minute? That’s insane. It’s a mechanical ballet.

Actionable insights for the history buff or hobbyist

If you're fascinated by the mechanics of who invented the gasoline engine, don't just read about it. Experience the evolution.

- Visit the Mercedes-Benz Museum: If you're ever in Stuttgart, go. Seeing the original 1886 Motorwagen in person makes you realize how fragile and brilliant the first gasoline engines were.

- Study the "Atmospheric" Engine: Look up videos of Otto’s early atmospheric engines. They don't use a crankshaft in the traditional way; they use gravity and vacuum. It’s a bizarre dead-end of evolution that is mesmerizing to watch.

- Check out the "Hit-and-Miss" Rallies: There are hobbyist groups all over the US and Europe that restore stationary engines from the late 1800s. Hearing one run is the only way to truly understand the "thump" that changed the world.

- Understand the Fuel: Read up on the history of "petroleum spirit." Understanding how we moved from coal gas to liquid gasoline explains why the engine had to change its design to accommodate carburetors.

The gasoline engine wasn't invented by a lone genius in a vacuum. It was a relay race. Lenoir started the jog, Otto picked up the pace, and Benz and Daimler sprinted across the finish line. Every time you turn the key (or push a button) today, you're triggering a sequence of events that took fifty years of failure to perfect.

---