If you ask a history buff who invented the gas mask, they’ll probably bark "Garrett Morgan" at you before you can even finish the sentence. Or maybe they’ll go the "Great War" route and talk about the British P Helmet or the German Respirator. Honestly? They’re all right. And they’re all wrong.

History is messy.

The reality is that nobody just woke up one day and "invented" the gas mask in a vacuum. It wasn't a singular "eureka" moment in a lab. It was a desperate, multi-century scramble to keep humans from dying while breathing in toxic junk. Whether it was a 16th-century doctor trying not to catch the Black Death or a 19th-century firefighter crawling through a smoky basement, the evolution of the gas mask is a story of trial, error, and a lot of dead canaries.

The Early Days: Sponges, Beaks, and Bad Vibes

Long before the chlorine gas of Ypres, people knew that breathing in certain things was a one-way ticket to the grave. But they didn't understand why.

In the 1600s, plague doctors wore those creepy bird-like masks. You’ve seen them in horror movies. Charles de Lorme is usually credited with that design. The "beak" wasn't for style; it was packed with aromatic herbs, camphor, and dried flowers. They thought disease was spread by "miasma" (bad smells). While the mask looked terrifying, it actually provided a primitive form of filtration, though it was mostly useless against the actual plague bacteria.

Fast forward to the 1700s. Miners were the real pioneers here. Alexander von Humboldt, a guy who seemingly did everything, developed a primitive respirator in 1799 for miners in Prussia. It was clunky. It barely worked. But it was a start.

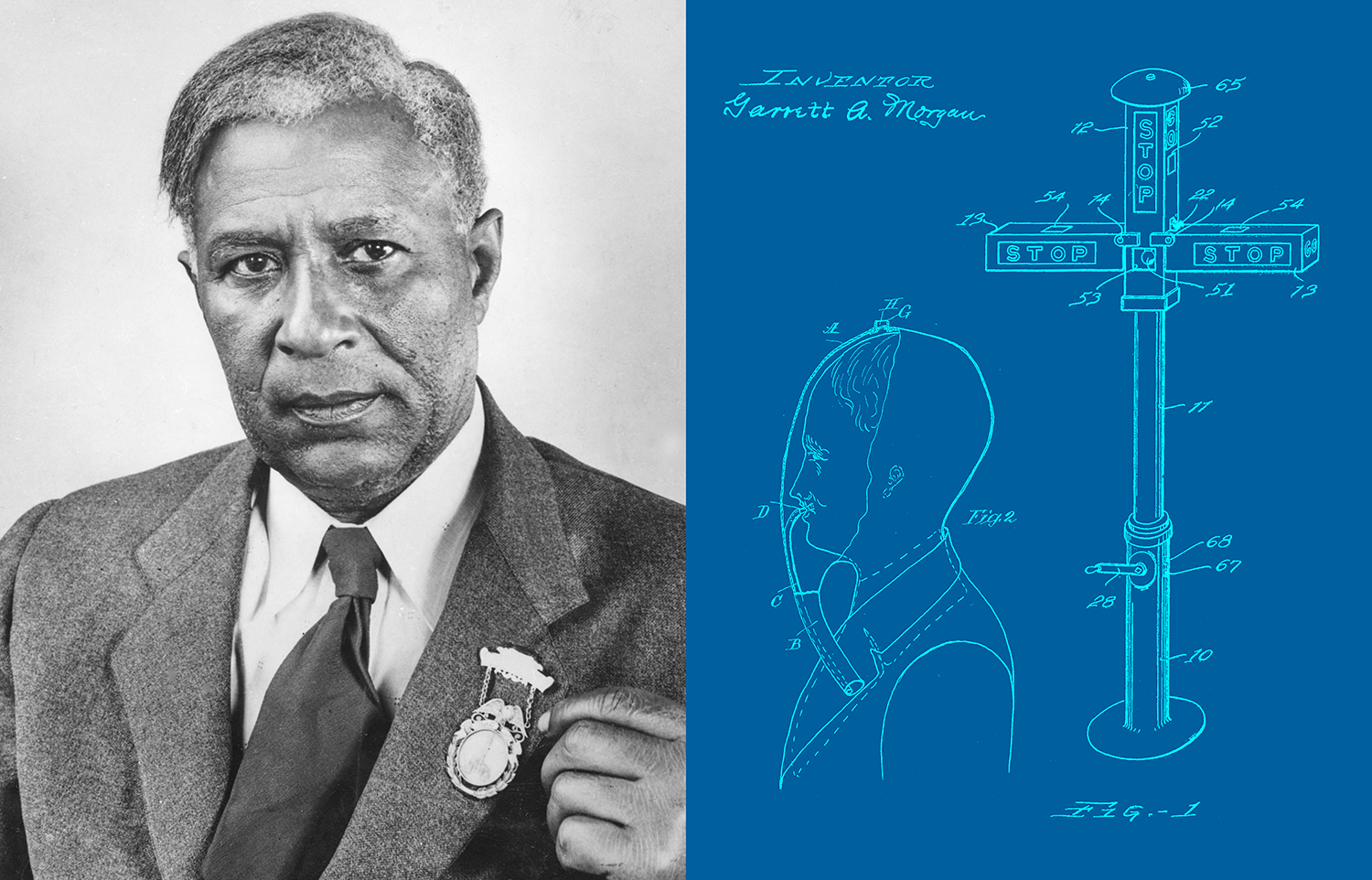

Garrett Morgan and the Safety Hood

Now we get to the name most people know. Garrett Morgan.

Morgan was an African American inventor in Cleveland, and in 1912, he patented the "Safety Hood." This wasn't a chemical warfare mask. It was designed for firefighters. Morgan realized that during a fire, the "cleanest" air is usually near the floor. His invention used a long tube that hung down to the ground, with a wet sponge at the end to cool the air and filter out some smoke.

The big moment for Morgan came in 1916. There was a massive explosion in a tunnel 250 feet beneath Lake Erie. Men were trapped. Rescuers were dying trying to get to them. Morgan and his brother put on the hoods, went into the smoke and toxic fumes, and started pulling people out.

📖 Related: New Update for iPhone Emojis Explained: Why the Pickle and Meteor are Just the Start

It worked. He saved lives.

But here’s the kicker: even though his invention was a success, Morgan faced massive racial prejudice. To sell his product in the South, he often had to hire a white actor to pretend to be the inventor while Morgan posed as a "Native American" assistant. It’s a wild, frustrating part of the story that shows how innovation isn't just about science—it's about the society it lives in.

The World War I Pivot: When Science Met Slaughter

Everything changed in April 1915. The Second Battle of Ypres. The German army released 168 tons of chlorine gas.

It was a massacre.

Soldiers had nothing to protect themselves. Some were told to soak cloths in their own urine and hold them over their mouths because the ammonia would theoretically neutralize the chlorine. It kinda worked, but it was a horrific stopgap.

The race was on. Scientists like Cluny MacPherson, a Canadian doctor, started experimenting with fabric hoods soaked in chemicals. He created the "MacPherson respirator," which was basically a canvas bag with a mica window. It was hot. It was suffocating. But it saved thousands of lives.

The Tyndall and Stenhouse Contribution

We can't talk about the gas mask without mentioning John Tyndall and John Stenhouse.

Stenhouse, a Scottish chemist, figured out in 1854 that charcoal was the secret sauce. He realized that wood charcoal could absorb vast amounts of gas from the air. If you look at a modern gas mask today, that basic principle of using activated charcoal is still the gold standard.

👉 See also: New DeWalt 20V Tools: What Most People Get Wrong

Tyndall took it a step further in the 1870s by adding a cotton wool filter to remove dust and smoke. He basically created the first "fireman’s respirator" that actually filtered particulates.

So, Who Really Won the Race?

If you're looking for one name to put on a plaque, you're going to be disappointed.

- Alexander von Humboldt gave us the mining prototype.

- John Stenhouse gave us the charcoal filtration.

- Garrett Morgan gave us the practical design for smoke and rescue.

- James Berton Garner and Nikolay Zelinsky (a Russian chemist) independently perfected the activated charcoal gas mask during WWI.

Zelinsky’s mask, developed in 1915, is probably the closest ancestor to what we see today. He refused to patent it, believing that his invention should belong to everyone to help save lives during the war.

The Tech Inside: How It Actually Works

Modern gas masks aren't just bags over your head. They are sophisticated pieces of life-support equipment. They generally use two methods:

- Mechanical Filtration: This is basically a very fine mesh (like an N95 mask) that stops tiny particles, soot, and bacteria from getting into your lungs.

- Adsorption: This is the chemical part. Activated charcoal is processed to have millions of tiny pores. These pores "trap" gas molecules through a process called London dispersion forces.

Some masks also use "chemisorption," where the filter is treated with reactive chemicals that actually neutralize specific toxins on contact. It’s basically a tiny, high-speed chemistry lab sitting on your face.

Common Misconceptions About Gas Masks

People watch movies and think a gas mask makes you invincible. It doesn't.

First off, a standard gas mask doesn't provide oxygen. If you walk into a room filled with nitrogen or carbon monoxide where there’s no oxygen, you’re still going to pass out. For that, you need an SCBA (Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus)—the big tanks firefighters wear.

Secondly, filters don't last forever. Depending on the concentration of the gas, a filter might be "spent" in as little as 15 minutes. Once those charcoal pores are full, the gas just sails right through.

✨ Don't miss: Memphis Doppler Weather Radar: Why Your App is Lying to You During Severe Storms

Finally, "one size fits all" is a lie. If you have a beard, a gas mask is basically a paperweight. The seal against your skin has to be perfect. Even a little bit of stubble can create a gap where lethal gas can leak in. This is why many military and first responder roles require people to be clean-shaven.

Why the Gas Mask Still Matters Today

We don't just use these for war anymore.

Industrial workers use them when handling pesticides or painting cars. Scientists use them when studying volcanoes or hazardous waste. They are essential for urban search and rescue.

The story of who invented the gas mask is really the story of human persistence. It’s about a dozen different inventors across three centuries, all trying to solve the same problem: how do we survive in an environment that is trying to kill us?

Take Action: Understanding Respiratory Safety

If you work in a DIY environment or a hobbyist shop, don't just grab a cheap dust mask and assume you're safe from fumes.

- Identify the Hazard: Is it dust? Is it organic vapors from paint? Is it acid gas?

- Check the Rating: Look for N95, P100, or specific chemical cartridges (usually color-coded).

- Fit Test: Put the mask on, cover the filters with your hands, and inhale. The mask should suck against your face. If you feel air leaking in, it’s not protecting you.

- Replace Filters Regularly: If you start to smell the chemicals you’re working with, the filter is dead. Change it immediately.

The history of the gas mask is written in the lives of the people who didn't have one when they needed it. Respect the tech, understand the history, and breathe easy.

Next Steps for Safety and Research

To dive deeper into respiratory protection, you should investigate the NIOSH (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) database. They provide the most rigorous testing standards for modern masks. If you are a history buff, look into the Garrett Morgan Museum or the archives of the Imperial War Museum to see the actual progression of the "Small Box Respirator" used in the trenches of France. For those interested in the chemistry, researching "Activated Carbon Adsorption Isotherms" will explain exactly how those charcoal filters trap molecules at a microscopic level.