You probably think there is one name attached to the typewriter. Like Edison with the bulb or Bell with the phone. But honestly, history is rarely that clean. If you're looking for a simple answer to who invented the first typewriter, you’re going to be disappointed because the "first" depends entirely on how you define "typewriter."

Was it the first patent? The first working model? Or the first one that didn't break after five minutes of use?

Most textbooks point to Christopher Latham Sholes. He’s the guy who gave us the QWERTY layout we’re still stuck with today on our iPhones. But Sholes was actually late to the party. By the time he sat down in a Milwaukee machine shop in the 1860s, people had been trying to build "writing machines" for over 150 years. It was a long, frustrating, and often bankrupting process for dozens of inventors across the globe.

🔗 Read more: T-Mobile Pay Your Bill Over the Phone: Why It Is Still the Fastest Way to Get It Done

The 1714 Ghost: Henry Mill’s "Artificial Machine"

The paper trail starts in England. In 1714, an engineer named Henry Mill received a patent from Queen Anne. The description was ambitious. He claimed to have invented an "artificial machine or method for the impressing or transcribing of letters, singly or progressively one after another, as in writing."

Here is the kicker: nobody knows what it looked like.

There are no surviving drawings. No prototype exists in a dusty museum basement. Some historians even wonder if he actually built the thing or just had a really good idea he wanted to protect. Because Mill didn't leave a physical legacy, he’s often relegated to a footnote. But conceptually? He was the first. He saw a world where "writing" didn't require a quill and a steady hand. He just couldn't quite make it a reality for the masses.

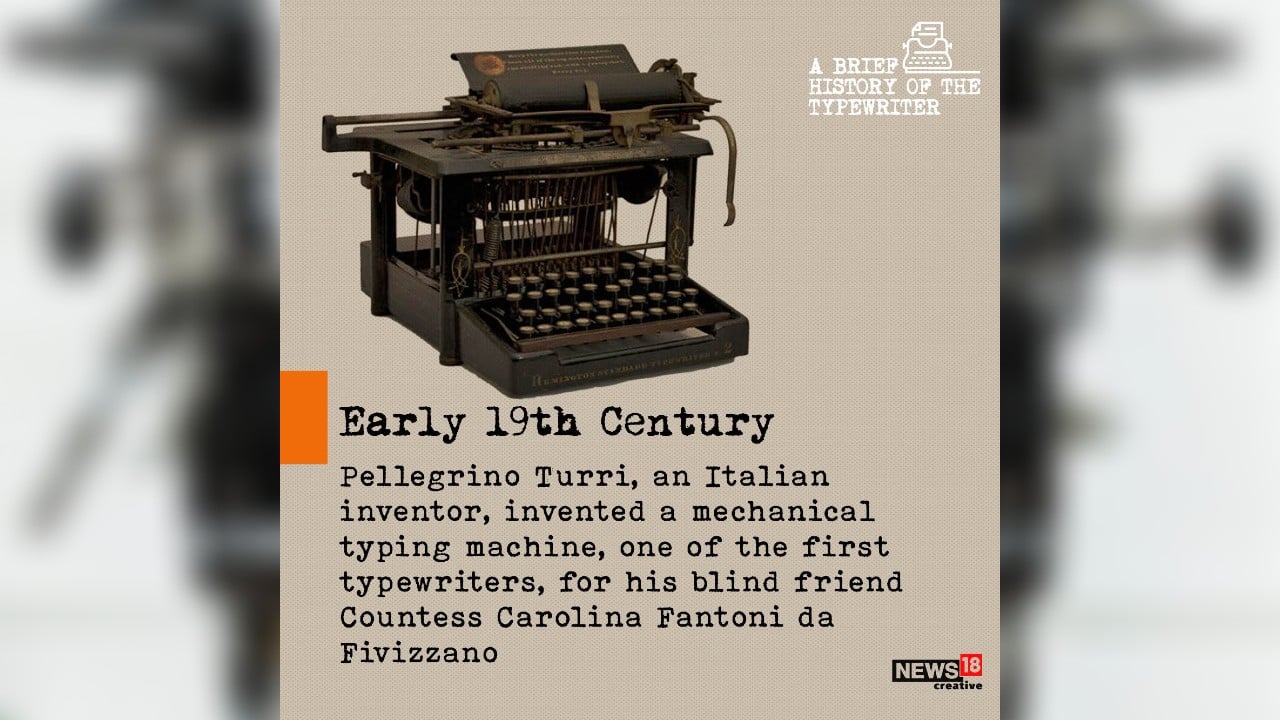

The Blindness Factor: Pelligrino Turri

Fast forward to 1808. We move to Italy. This is where the story gets a bit more personal and, frankly, more interesting. Pelligrino Turri didn't want to disrupt the printing industry. He just wanted to help a friend.

Countess Carolina Fantoni da Fivizzano was blind. In the early 19th century, if you couldn't see, you couldn't write private letters. You had to dictate them to a scribe. No privacy. No secret romances. Turri built a machine so the Countess could type her own letters by touch.

While we don't have the machine, we actually have the letters. They still exist in Italian archives. They are the first physical evidence of typed text in human history. Turri is also credited with inventing carbon paper to provide the "ink" for his machine. It worked. It was functional. But it wasn't a commercial product. It was a gift of love and utility.

Why the "Typowriter" Failed

In 1829, an American named William Austin Burt patented something called the "Typowriter." It looked like a giant wooden box with a swinging lever.

It was slow.

Incredibly slow.

Burt’s machine required the user to turn a dial to select a letter and then press a lever down to ink it onto the paper. You could literally write faster with a pen, even if you had terrible handwriting. Even though he’s technically the first American to patent a writing machine, it was a total commercial flop. He couldn't find a single person to invest in it.

The Mid-Century Explosion

Between 1830 and 1860, the race heated up. It was like the Silicon Valley of the 19th century.

- Xavier Progin (1833): A French inventor who used "typographic rods." It was the first time we saw the idea of separate keys for each letter.

- Charles Thurber (1843): He focused on helping the "nervous" writer. His machine was a massive wheel of type, but again, it was too slow for business use.

- Giuseppe Ravizza (1855): He called his invention the Cembalo scrivano or "scribbling harpsichord." It’s widely considered the most advanced machine before the modern era.

The problem wasn't the idea. It was the engineering. The keys kept jamming. The ribbon wouldn't advance. The paper wouldn't stay straight. It was a mechanical nightmare that required a genius to operate and a mechanic to maintain.

Sholes, Glidden, and the Birth of QWERTY

Now we get to the name everyone remembers: Christopher Latham Sholes. Along with Samuel Soule and Carlos Glidden, Sholes began working on a machine to number book pages in 1867. Glidden supposedly asked, "Why can't you make a machine that will print letters?"

Sholes took the bait.

Their first model used a telegraph key and a piece of glass. It was crude. But Sholes was persistent. He spent years iterating. He went through dozens of prototypes. He was the first to realize that the machine didn't just need to work; it needed to be fast enough to beat a pen.

This is where the QWERTY legend comes in. People often say QWERTY was designed to slow typists down so the bars wouldn't jam. That’s mostly a myth. It was actually designed based on feedback from telegraph operators who were transcribing Morse code. They needed certain letter combinations far apart so the mechanical "arms" of the typewriter wouldn't collide when hit in quick succession.

In 1873, Sholes ran out of money and patience. He sold the rights to E. Remington and Sons. Yes, the gun makers.

The Remington No. 1: Success at Last?

Remington had the precision machinery to actually build these things at scale. They released the Remington No. 1 in 1874.

It was a weird device. It was mounted on a sewing machine stand, complete with a foot pedal for the carriage return. You couldn't even see what you were typing because the keys struck the bottom of the platen (the roller). You had to lift the whole carriage up to see if you'd made a typo.

It wasn't an instant hit. It was expensive—about $125. That was a fortune back then. Mark Twain was one of the first people to buy one, though he famously grew frustrated with it. He eventually became the first author to submit a typed manuscript (Life on the Mississippi), but he hated the "nuisance" of the machine.

How to Verify a "First" Invention

If you're researching this for school or just a deep-seated curiosity, you have to look at the primary sources. Historians usually split the credit based on these three milestones:

- The Conceptual First: Henry Mill (1714). He had the vision but no proof of a build.

- The Functional First: Pelligrino Turri (1808). He proved it could be done for a specific user.

- The Commercial First: Sholes and Remington (1874). They turned a gadget into a global industry.

Most people settle on Sholes because his machine actually stuck. It’s the direct ancestor of the laptop you’re probably using right now.

Taking Action: Where to See These Machines

If you really want to understand the scale of these things, you have to see them. Pictures don't do justice to how heavy and intricate they are.

- Visit a Museum: The Smithsonian National Museum of American History has an incredible collection of early writing machines, including Burt’s "Typowriter" (a replica, as the original was lost in a fire).

- Check the Patent Records: You can search the Google Patents database for Patent No. 79,265 to see Sholes' original 1868 design. It's fascinating to see how much it looks like a piano.

- Try "Blind Typing": To appreciate Turri’s 1808 invention, try typing a paragraph on your keyboard with the monitor off. It highlights why the "visible writing" machines of the 1880s were such a massive breakthrough.

The typewriter didn't just change how we wrote; it changed who worked. It was the machine that brought women into the office en masse in the late 19th century. So, while Sholes gets the credit on the bronze plaque, the typewriter was actually the result of a century-long relay race involving Italian counts, English engineers, and American tinkerers.

If you're looking for a specific starting point for your own collection or research, start with the Remington No. 2. It was the first "shift key" machine, allowing for both upper and lowercase letters. That was the moment the typewriter truly became a replacement for the human hand.