Ever sat under a ceiling fan on a sweltering July afternoon and wondered whose idea it was to slap a propeller on a motor? We take it for granted. It's just a button we push. But the story of who invented the electric fan isn't just a simple name and a date. It’s a messy, spark-filled history of the early Gilded Age.

Schuyler Skaats Wheeler. That's the name you’re looking for.

In 1882, this twenty-two-year-old engineer decided he was tired of being hot. Or maybe he just saw a gap in the rapidly expanding world of "direct current" electricity. Either way, Wheeler took a small electric motor and attached a two-bladed propeller to the end of it. No cage. No safety features. Just a spinning blade of death that happened to move air.

He didn't have a startup. He didn't have a Kickstarter. He just had the audacity to realize that electricity didn't just have to power lightbulbs; it could create motion.

The 1880s: A dangerous time to be hot

Before Wheeler, if you wanted to stay cool, you were basically relying on physics or servants. You had the punka—those giant rectangular cloth fans hung from ceilings in India and the Middle East, pulled manually by a person standing in the corner. You had hand fans. You had architectural tricks like high ceilings and cross-breezes.

Then came 1882.

Wheeler was working for the Crocker & Curtis Electric Motor Company at the time. His invention was a desktop model. It was tiny compared to the industrial behemoths we see today, but it was revolutionary. It used "Type L" motors. Imagine a piece of cast iron and copper wire that buzzed like a hive of angry bees.

These early models weren't for the masses. They were luxury items for the ultra-wealthy. Think about it: most homes didn't even have electrical wiring yet. If you had an electric fan in 1885, you were essentially the 19th-century version of someone owning a private jet today. You were elite. You were "electrified."

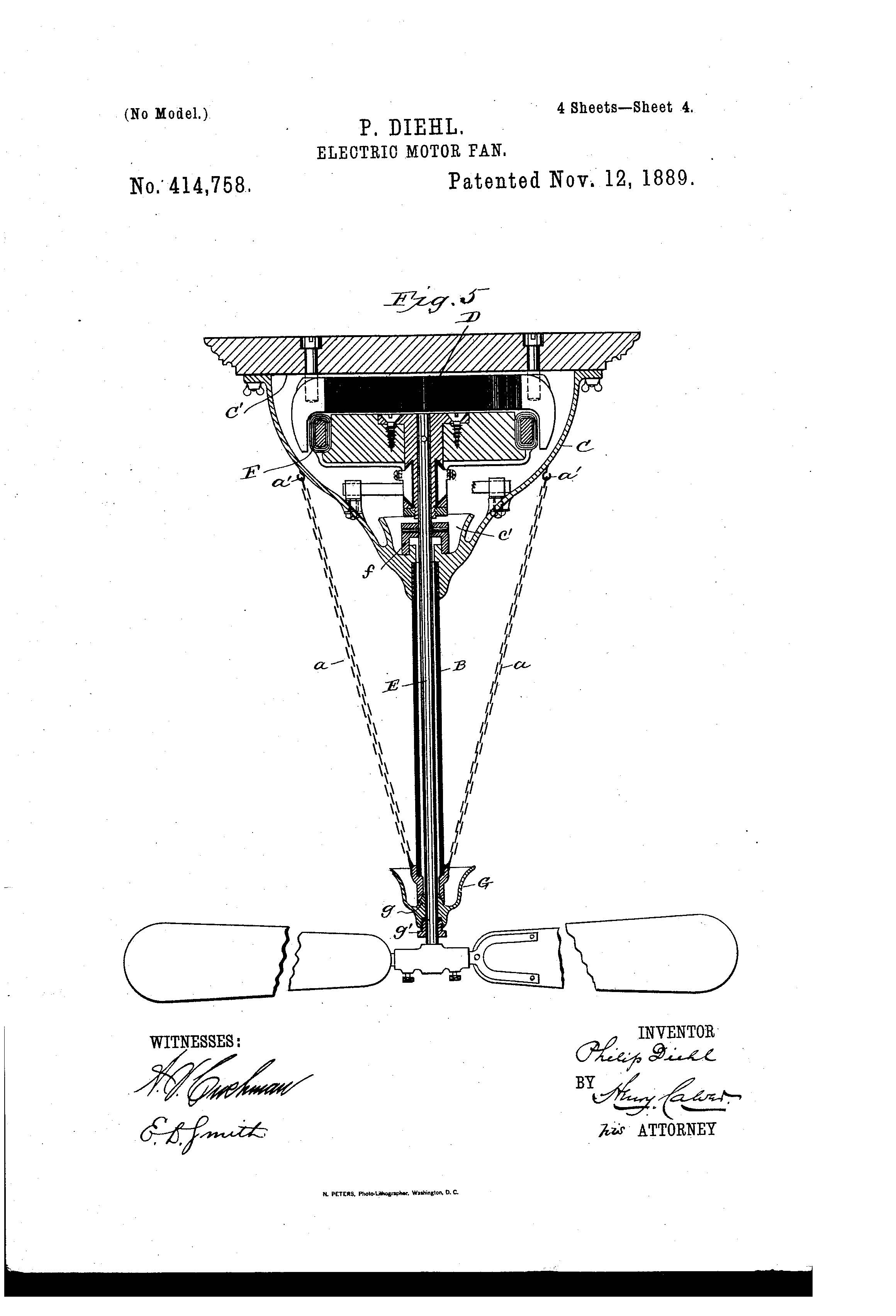

Why Philip Diehl matters just as much

If Wheeler invented the desk fan, Philip Diehl is the guy who looked at the ceiling and had a lightbulb moment. Literally.

Diehl was a contemporary of Thomas Edison. In 1887, he took an electric motor—originally designed for Singer sewing machines—and mounted it to the ceiling. This was the birth of the ceiling fan.

🔗 Read more: Why the Pen and Paper Emoji is Actually the Most Important Tool in Your Digital Toolbox

It solved a massive problem. Desk fans were localized. They blew papers everywhere. They were dangerous for curious fingers. But a ceiling fan? That moved the whole room. Diehl's design even included a light fixture eventually, because why use two mounting points when one would do?

Honestly, the rivalry between these early inventors wasn't even a rivalry; it was more like a land grab for different parts of the house. Wheeler owned the desk. Diehl owned the ceiling.

The evolution of the blades

The first fans only had two blades. Why? Because it was cheaper to balance two blades than four. High-speed photography didn't exist, and precision manufacturing was still in its infancy. If a fan was off-balance, the whole thing would vibrate until it walked itself right off the table.

As manufacturing improved, we saw the shift to three, four, and six blades. But here is a weird fact: more blades don't necessarily mean more air. They usually just mean a quieter fan. Two blades are actually incredibly efficient for moving high volumes of air at high speeds, but they sound like a helicopter taking off in your living room.

The brass era and the safety problem

By the early 1900s, companies like Westinghouse and General Electric (GE) started mass-producing these machines. This was the "Brass Era." If you find one of these at an antique mall, you’ll notice they are incredibly heavy. That's because they are made of solid cast iron and brass.

They also didn't have cages.

Early fans were basically open-air blenders. It wasn't until the 1910s and 20s that manufacturers realized that maybe, just maybe, people didn't want to lose a finger while trying to cool down. The evolution of the "birdcage" guard changed the aesthetics of the fan forever. We went from raw industrial tools to household appliances.

The motor wars: AC vs DC

You can't talk about who invented the electric fan without mentioning the war of the currents. Wheeler’s first fans ran on Direct Current (DC). This was fine if you lived in a city center powered by an Edison plant. But as Nikola Tesla’s Alternating Current (AC) took over the world, fan motors had to adapt.

The introduction of the induction motor by Tesla made fans cheaper, more reliable, and much longer-lasting. No brushes to wear out. No sparks flying from the motor housing. Just smooth, oscillating motion.

💡 You might also like: robinhood swe intern interview process: What Most People Get Wrong

What most people get wrong about "Ancient" fans

Sometimes you’ll see articles claiming the Chinese or Romans "invented the fan."

Well, yeah. They invented fans.

The rotary fan—a wheel with blades—was actually documented in China around 180 AD by an inventor named Ding Huan. It was a massive seven-wheeled fan that was powered by prisoners or laborers turning a crank. It worked on the same principle of fluid dynamics as Wheeler’s fan, but without the "electric" part, it’s just a big manual labor machine.

Wheeler’s genius wasn't the fan itself. It was the marriage of the fan to the electron. He took the sweat out of the equation.

The tech inside your modern fan

Today, we have Dyson "bladeless" fans (which actually have blades hidden in the base) and DC-motor ceiling fans that use 70% less electricity than the ones from the 90s.

We use Brushless DC (BLDC) motors now. These are incredibly sophisticated. They use permanent magnets and electronic controllers to pulse electricity to the motor, allowing for infinite speed control. Your great-grandfather’s fan basically had "On," "Off," and "Maybe."

- Materials: We’ve moved from brass to steel, then to plastic, and now back to high-end composites and wood.

- Oscillation: The mechanism that makes a fan turn side-to-side was a mechanical marvel of the 1900s, using a series of gears linked to the main motor shaft.

- Smart Integration: Now you can talk to your fan. "Alexa, I'm sweating." It’s a long way from Wheeler’s 1882 death-trap.

Why did it take so long to catch on?

You’d think everyone would want one immediately. They didn't.

Ice was the competition.

In the late 1800s, the "Ice King" Frederic Tudor had convinced the world that large blocks of frozen lake water were the only way to stay cool. People had "ice boxes," not refrigerators. They put ice in front of passive vents. The electric fan was seen as a noisy, buzzing fad.

📖 Related: Why Everyone Is Looking for an AI Photo Editor Freedaily Download Right Now

It took the 1902 invention of modern air conditioning by Willis Carrier to actually help the fan industry. Fans and AC units work together. Fans move the chilled air. Without the fan, the AC unit just creates a cold puddle on the floor.

Real-world impact of Wheeler’s invention

Wheeler didn't just give us a cool breeze. He fundamentally changed how we build cities.

Before the electric fan, factories were unbearable in the summer. Productivity plummeted. By installing massive industrial fans, owners could keep workers on the line longer. It’s a bit of a dark side to the invention—it enabled longer, more grueling workdays in harsh environments.

But it also saved lives. In the crowded tenements of New York and Chicago, heatstroke was a massive killer in the 1890s. A simple electric fan could drop the perceived temperature enough to keep a person's core temp from reaching the breaking point.

Is the fan obsolete?

Honestly? No.

Air conditioning is expensive. It’s heavy. It’s bad for the environment because of the refrigerants and high power draw. A fan, however, is incredibly efficient. It doesn't actually lower the temperature of the room—it just speeds up the evaporation of sweat on your skin. That’s the "wind chill" effect.

Because of this, fans are seeing a massive resurgence in "green" architecture. Using a high-volume, low-speed (HVLS) fan can allow a building to set its thermostat 4 degrees higher without anyone noticing. That’s a huge energy saving.

Actionable insights for your own home

If you're looking to honor Schuyler Wheeler's legacy and actually stay cool, here is what you need to do:

- Check the direction: In the summer, your ceiling fan should spin counter-clockwise (pushing air down). In the winter, flip the switch on the motor housing so it spins clockwise. This pulls cold air up and pushes the warm air trapped at the ceiling back down to you.

- Clean the leading edge: Dust on the edge of the blade creates drag. A dirty fan can be up to 20% less efficient and much noisier. Use an old pillowcase to slide over the blade and pull the dust off without it falling on your bed.

- Position for cross-ventilation: Don't just point a desk fan at your face. Point it out an open window if the air inside is hotter than the air outside. This creates a vacuum that pulls cooler air in through other openings.

- Know when to upgrade: If your fan is humming loudly or "clicking," the bearings are shot. Modern BLDC motor fans are nearly silent and pay for themselves in energy savings within two years if you use them daily.

Schuyler Wheeler died in 1923. He lived long enough to see his "Type L" motor evolve into a household necessity. He wasn't just an inventor; he was the guy who realized that we don't have to be victims of the weather. We just need a little bit of voltage and a lot of rotation.

Next time you hear that familiar whirring sound, remember the 22-year-old kid in 1882 who just wanted a breeze. He changed everything.