If you’re looking for a name to drop at a trivia night, the answer is Alessandro Volta. He’s the guy. In 1800, he stacked some metal discs and essentially changed how humans live forever. But honestly? The story of who invented the electric battery is way weirder than just some Italian guy playing with coins. It actually starts with a dead frog.

Science is rarely a "eureka" moment in a vacuum. It’s usually a series of people being loud and wrong until someone finally gets it right. Before Volta gave us the "Voltaic Pile," the world thought electricity was something only living creatures could make. They called it "animal electricity." It sounds like something out of a low-budget sci-fi movie, but in the late 1700s, it was the peak of scientific theory.

The Frog Leg Feud That Started It All

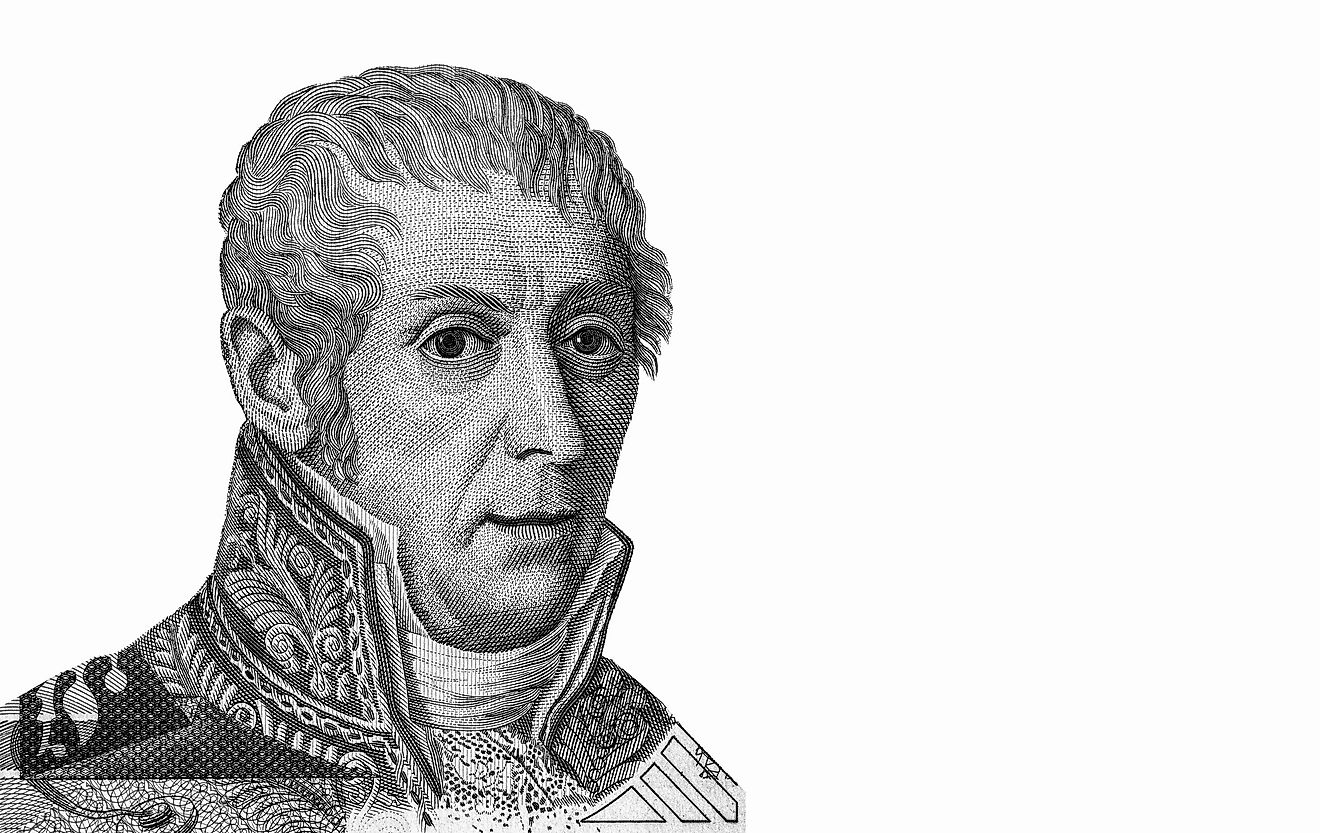

Enter Luigi Galvani. He was a physician and a contemporary of Volta. One day in 1780, while he was dissecting a frog, his scalpel touched a brass hook holding the frog's leg. The leg kicked. The frog was very dead, yet the muscle moved. Galvani was convinced he’d found the "spark of life." He believed that a vital force—an electrical fluid—flowed through the nerves of animals.

Volta wasn't buying it. At first, he thought Galvani was onto something, but he was a skeptic by nature. He started experimenting and realized the frog was just acting as a conductor. The actual "electricity" was coming from the two different metals (the steel scalpel and the brass hook) being connected by a moist medium (the frog).

This sparked one of the greatest beefs in scientific history.

Volta set out to prove that you didn't need a dead animal to make a current. He realized that if you put two different metals in contact with a salty or acidic liquid, you could create a flow of charge. He replaced the frog with brine-soaked cardboard. It worked. By 1800, he had built the first "pile."

How the First Battery Actually Worked

The original battery was literally a stack. Volta took discs of copper and zinc and separated them with pieces of cardboard soaked in saltwater (electrolyte).

$$Zn \rightarrow Zn^{2+} + 2e^-$$

👉 See also: Pi Coin Price in USD: Why Most Predictions Are Completely Wrong

In modern terms, the zinc was oxidizing. It was losing electrons. Those electrons wanted to get over to the copper side. Because he stacked these pairs on top of each other, the voltage increased with every layer. It was the first time in human history we had a steady, continuous flow of electricity. Before this, we only had static electricity—like when you rub your socks on a carpet and zap a doorknob. Useful for a prank, but you can't power a lightbulb with a static pop.

The Construction of the Pile

- The Anode: Zinc discs that would slowly corrode as they gave up electrons.

- The Cathode: Copper discs that received the flow.

- The Electrolyte: Brine-soaked leather or cardboard. This allowed ions to move but kept the metals from touching directly and shorting out.

It was messy. It leaked. It didn't last very long because the electrolyte would dry out or the zinc would get gunked up with bubbles. But it was a proof of concept that changed everything. Napoleon Bonaparte was so impressed he made Volta a count. Not a bad day at the office.

Why We Almost Missed Out on the Battery

There is a persistent rumor that the Baghdad Battery—a clay jar containing a copper cylinder and an iron rod found in modern-day Iraq—predates Volta by 2,000 years. Some people love the idea that ancient civilizations had electricity.

While the Baghdad Battery can generate a small voltage if you fill it with vinegar, there is zero evidence it was actually used as a battery. Most archaeologists believe these jars were used for storing scrolls or for electroplating jewelry. Even if it was a battery, the knowledge was lost. It didn't lead to a power grid. It didn't lead to your iPhone. Who invented the electric battery in a way that actually mattered for the modern world? That’s still Volta.

The Evolution: Beyond the Pile

Volta’s invention was the spark, but it was incredibly impractical for anything other than lab experiments. You couldn't exactly tip it over without getting acid everywhere.

In 1836, John Frederic Daniell, an English chemist, came along and fixed the "fizzing" problem. Volta’s battery suffered from polarization—hydrogen bubbles would form on the copper and block the current. Daniell used two different electrolytes and a porous pot to separate them. This was the Daniell Cell. It became the standard for powering telegraphs. If you’ve ever wondered how people sent Morse code across continents in the 1800s, you can thank Daniell for making Volta's idea stable.

Then came the "Dry Cell." In 1886, Carl Gassner figured out how to turn the liquid electrolyte into a paste. This was the birth of the battery you actually recognize. Suddenly, batteries were portable. You could put them in a flashlight (invented shortly after) without worrying about spilling brine on your shoes.

✨ Don't miss: Oculus Rift: Why the Headset That Started It All Still Matters in 2026

The Lead-Acid Breakthrough

While the dry cell was great for small things, we needed something heavy-duty. In 1859, Gaston Planté invented the lead-acid battery. This was the first rechargeable battery.

It’s kind of wild that the technology under the hood of your gas-powered car today—that big heavy lead block—is basically 160-year-old tech. It works because the chemical reaction is reversible. When you run a current back into the battery, you "reset" the lead plates. It's inefficient and heavy, but it’s incredibly reliable for providing a huge burst of power to start an engine.

The Lithium-Ion Revolution (The Modern Era)

Fast forward to the 1970s and 80s. The world wanted smaller, lighter, and more powerful. Lead was too heavy. Nickel-cadmium had a "memory effect" where it would forget its full capacity if you didn't drain it all the way.

John Goodenough, Stanley Whittingham, and Akira Yoshino won the Nobel Prize for developing the Lithium-ion battery. They realized lithium was the "secret sauce" because it's the lightest metal and has a massive electrochemical potential.

But lithium is also "angy." It’s highly reactive. If you’ve ever seen a laptop battery swell or catch fire, that’s the downside of packing that much energy into a small space. We are currently living in the "Lithium Age," but researchers are already looking for the next Volta-level breakthrough, like solid-state batteries that won't catch fire and can charge in minutes.

Common Misconceptions About the Battery

People get a lot of things wrong about this history.

- Benjamin Franklin didn't invent the battery. He coined the term "battery" (comparing a group of capacitors to a battery of cannons), but he was working with Leyden jars, which store static electricity, not chemical electricity.

- The "Voltaic Pile" wasn't a "discovery." It was an invention. Volta didn't find it in nature; he engineered it specifically to disprove a rival's theory.

- It wasn't a sudden success. Most scientists at the time thought it was a toy. It took decades for practical applications like the telegraph to make batteries essential.

Summary of the Battery Timeline

If you want to track the lineage of who invented the electric battery and how it grew, the chain looks roughly like this:

🔗 Read more: New Update for iPhone Emojis Explained: Why the Pickle and Meteor are Just the Start

- 1780s: Galvani notices dead frogs twitching and incorrectly guesses "animal electricity."

- 1800: Volta proves Galvani wrong by building the first chemical battery (The Pile).

- 1836: Daniell creates a version that doesn't stop working after 20 minutes.

- 1859: Planté gives us the ability to recharge batteries for the first time.

- 1880s: Gassner makes them "dry" and portable.

- 1980s: The modern lithium-ion tech we use for smartphones is perfected.

Actionable Insights for the Modern User

Understanding the history of the battery isn't just for history buffs; it helps you take better care of the tech you own today.

Check your chemistry. If you are buying backup power for your home, you’re likely choosing between Lead-Acid (Planté’s legacy) and Lithium-Iron Phosphate (LiFePO4). Lead-acid is cheap but dies after 3–5 years. LiFePO4 lasts 10 years but costs more upfront.

Respect the heat. All batteries, from Volta's brine-soaked rags to your iPhone 15, rely on chemical reactions. Heat speeds up these reactions, but it also speeds up the degradation of the battery components. Keep your devices cool to extend their lifespan.

Don't let them "bottom out." Unlike the old Nickel batteries of the 90s, modern Lithium batteries hate being at 0%. If you have a device you aren't using, store it at about 50% charge. Leaving it at 0% can cause the chemistry to "sleep" permanently, rendering it a paperweight.

Recycle correctly. Batteries are full of heavy metals and reactive chemicals. Tossing them in the trash is a fire hazard and an environmental nightmare. Most major tech retailers have drop-off bins for old Li-ion cells.

The jump from a stack of silver coins and salty leather to the battery in a Tesla is a massive leap, but the core principle hasn't changed. It's still just metals and chemicals playing a game of "pass the electron." Knowing who invented the electric battery helps us appreciate just how much work it took to get to the point where we can carry the world's knowledge in our pockets, powered by a tiny thin slab of lithium.

To further understand the mechanics of energy storage, look into the difference between "Energy Density" and "Power Density." This explains why your phone battery can't start a car, even though it can power a screen for ten hours.