You’re standing at a hole in a wall in a rain-slicked London street, or maybe a sun-drenched corner in Phoenix, punching in four digits. You want twenty bucks. You get twenty bucks. It feels like magic, but it's actually the result of a decades-long fistfight between different inventors, banks, and engineers. If you ask a trivia host who invented the cash machine, they’ll probably bark back "John Shepherd-Barron."

They aren't exactly wrong. But they aren't exactly right, either.

History loves a lone genius. We want a guy sitting in a bathtub who suddenly shouts "Eureka!" and changes the world. In reality, the automated teller machine (ATM) didn't have one father; it had a dozen uncles who all claimed paternity after the kid got rich. The story involves a guy who got the idea in a bathtub (seriously), a professional photographer, a Turkish-American inventor with over 1,300 patents, and a lot of radioactive ink.

The Bathtub Epiphany of John Shepherd-Barron

In the mid-1960s, John Shepherd-Barron was a managing director at De La Rue, a company that printed banknotes. One Saturday, he arrived at his bank one minute too late. The doors were locked. He was broke for the weekend.

Later that night, soaking in the tub, he started thinking about chocolate. Specifically, he thought about vending machines that spit out a bar of Dairy Milk in exchange for a coin. Why couldn't a machine do that with money?

He pitched the idea to Barclays. Over a "pink gin" lunch—which is about as 1960s British as you can get—he convinced the bank's general manager to try it. On June 27, 1967, the world's first "De La Rue Automatic Cashier" was installed at a Barclays branch in Enfield, North London.

It was primitive.

💡 You might also like: Heavy Aircraft Integrated Avionics: Why the Cockpit is Becoming a Giant Smartphone

There were no plastic cards with magnetic strips. Instead, you used a paper check impregnated with Carbon-14, a radioactive substance. The machine detected the radiation, matched it to a four-digit PIN, and spit out a £10 note. Shepherd-Barron originally wanted a six-digit PIN because he remembered his army service number, but his wife, Caroline, told him she could only remember four digits. That’s basically why your bank account is protected by a four-digit code today.

But Wait, Someone Else Was Earlier

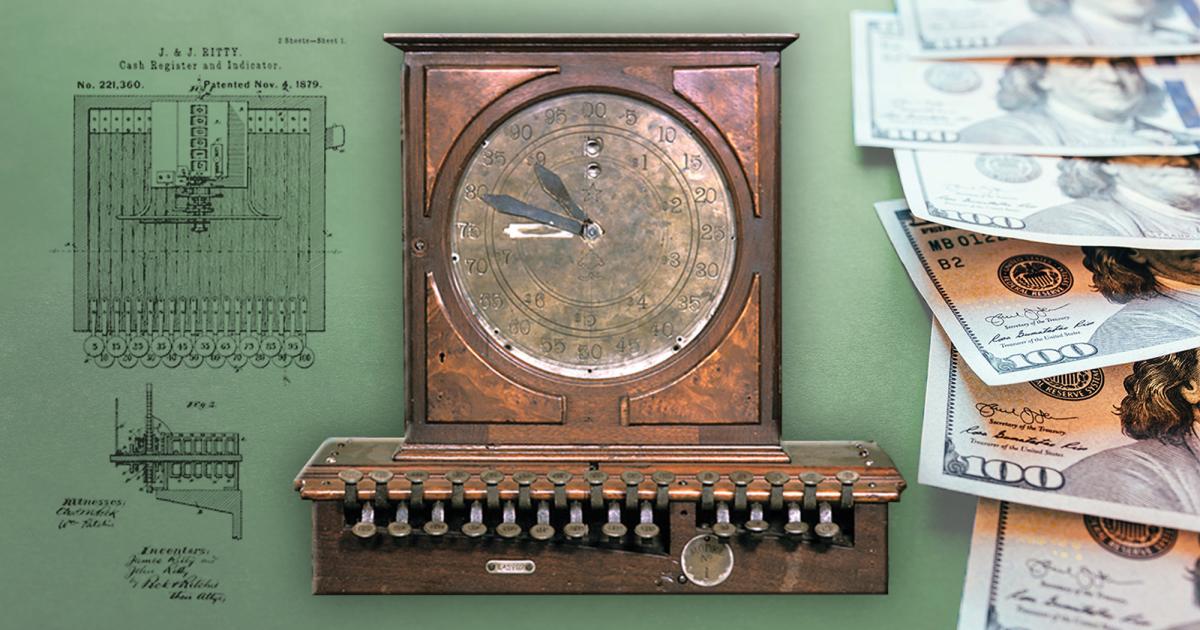

If we are being technical about who invented the cash machine, Shepherd-Barron has a massive rival for the title: Luther George Simjian.

Simjian was a prolific inventor who moved to the U.S. from Turkey. In 1960—seven years before the Barclays machine—he convinced New York’s City Bank of Albany (now Citibank) to install a device he called the "Bankograph."

It was a beast. It allowed customers to deposit cash or checks and receive a receipt, all without a teller. Simjian’s machine didn't just dispense cash; it focused on the deposit side. But here’s the kicker: nobody used it.

Simjian famously noted that the only people using his machine were "prostitutes and gamblers" who didn't want to look a teller in the eye. After six months, the bank pulled the plug. It was a failure of psychology, not technology. Simjian was right about the future, but he was too early for the public's comfort zone.

The Scottish Connection and the Plastic Card

While London was playing with radioactive checks, James Goodfellow in Scotland was working on something that looks much more like the modern ATM.

📖 Related: Astronauts Stuck in Space: What Really Happens When the Return Flight Gets Cancelled

In 1966, Goodfellow, an engineer for Kelvin Hughes, was tasked with finding a way to dispense money after hours. He didn't like the idea of radioactive paper. He developed a system using a plastic card with punched holes and a PIN keypad.

Goodfellow holds the first UK patent for the ATM (filed in 1966). For a long time, he was the forgotten man of banking history. Shepherd-Barron got the OBE and the fame because his machine went live first, but Goodfellow’s design—using a physical card and a keypad—is the actual ancestor of what’s in your wallet right now.

It’s a classic case of the difference between "who built it first" and "who patented the idea that actually worked."

Don Wetzel and the American Boom

Across the pond, the Americans were busy perfecting the "magstripe." Don Wetzel, a vice president at Docutel, is often credited with the first modern American ATM in 1969.

Wetzel’s story is similarly mundane. He was waiting in a long line at a Dallas bank and got annoyed. He thought, "I can do this better." His machine, installed at Chemical Bank in Rockville Centre, New York, used a plastic card with a magnetic strip to store account information.

This was the bridge.

👉 See also: EU DMA Enforcement News Today: Why the "Consent or Pay" Wars Are Just Getting Started

The Chemical Bank machine was the first to use the magnetic technology we recognize. The bank’s marketing was aggressive, using the slogan: "On Sept. 2nd, our bank will open at 9:00 and never close again."

Why Does This Matter?

You might think arguing about who invented the cash machine is just academic pedantry. It isn't. It's a lesson in how innovation actually happens. It’s never a straight line. It’s a messy, overlapping web of people solving the same problem at the same time because the culture is ready for it.

The ATM changed the world in ways we forget. It killed the "banker's hours" (10 a.m. to 3 p.m.). It paved the way for self-service culture. Without the ATM, we likely wouldn't have self-checkout at grocery stores or online banking. It was the first time the general public was trusted to interact with a high-stakes computer without a professional standing over their shoulder.

The Misconceptions

- Radiation: People often freak out when they hear Shepherd-Barron’s machine used radioactive Carbon-14. Honestly, it was a tiny amount. You’d have to eat several hundred of those checks to feel any ill effects, according to the inventor.

- The PIN: We didn't always have PINs. Some early machines used physical keys. The PIN was the breakthrough that made the system scalable.

- The "First": There is no "first" ATM. There is the first deposit machine (Simjian), the first cash dispenser (Shepherd-Barron), the first patented keypad system (Goodfellow), and the first magnetic strip machine (Wetzel).

The Future of the Hole in the Wall

We’re moving toward a cashless society, or so the headlines tell us. But ATMs aren't dying; they're evolving. You see them now with video tellers, cryptocurrency integration, and biometric scanners that read the veins in your palm.

If you're researching this because you want to know who to thank—or blame—for your banking fees, the answer is a committee of frustrated people in the 1960s who were tired of waiting in line.

Actionable Insights for the Modern User

If you want to maximize your interaction with the descendants of these inventions, keep these specific tips in mind:

- Check the Skimmer: Before you slide your card into any machine, especially those in high-traffic tourist areas or outdoor gas stations, give the card reader a firm tug. If it’s loose or feels like a "sleeve" over the real hardware, walk away. Criminals have evolved just as fast as the inventors.

- Use Contactless: Most modern ATMs now support NFC (near-field communication). Tapping your phone or card is significantly more secure than swiping, as it uses a one-time token rather than transmitting your actual card data through the magstripe reader.

- Bank Choice Matters: If you hate the fees that grew out of this invention, look for "Allpoint" or "MoneyPass" networks. Many online-only banks use these networks to give you fee-free access to ATMs in CVS, Target, or Walgreens.

- Audit Your PIN: If you are still using 1234, 0000, or your birth year, you are negating sixty years of security engineering. A four-digit PIN has 10,000 possible combinations. Don't pick the top three.

The ATM was the first "robot" most people ever interacted with. Whether you credit the man in the bathtub or the engineer in the lab, it remains one of the most successful pieces of technology in human history because it solved a universal human problem: wanting your own money when you want it.

Next Steps for Your Research:

To truly understand the evolution of this tech, you should look into the history of the magnetic stripe, specifically the work of IBM engineer Forrest Parry. While the ATM gave us the machine, Parry’s work with a strip of tape and a hair dryer gave us the card that made the whole global network possible. Check out the archives of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History for photos of the original 1960s prototypes.