You’re probably reading this on a Tuesday afternoon, maybe eyeing the clock and wondering why on earth we all agreed that forty hours is the magic number. It feels like a law of nature. It’s not. In fact, if you’d asked a factory worker in the mid-1800s about a forty-hour week, they would’ve thought you were describing a vacation. Back then, "sunup to sundown" wasn't a poetic phrase; it was a grueling, literal reality that often stretched into 80 or 100 hours of bone-breaking labor every single week.

So, who invented the 40 hour work week?

If you search for a quick answer, you’ll likely see the name Henry Ford pop up. People love a simple narrative. They love the idea of one visionary titan of industry snapping his fingers and changing the world for the better. But history is messier than a LinkedIn thought-leader post. Ford didn’t just wake up one day and decide to be generous. He was responding to decades of bloody protests, radical labor organizing, and a shifting economic landscape that made shorter hours more profitable than long ones.

✨ Don't miss: TV Stations in the US: Why Most People Get the "Death of TV" Wrong

The Long, Violent Road to the Eight-Hour Day

Before we get to the 1920s and the assembly line, we have to talk about the 1860s. This is where the real "invention" happened. It wasn't invented by a CEO in a suit; it was invented by workers who were tired of dying in mills.

The slogan was simple: "Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, and eight hours for what we will."

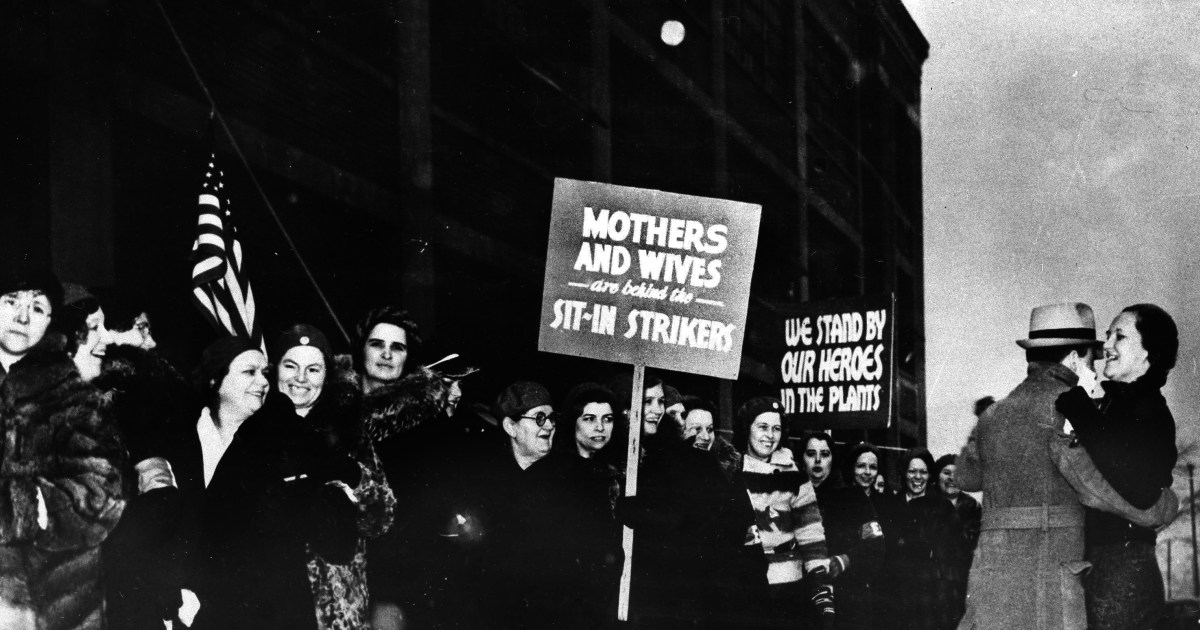

It sounds catchy now. In the 1880s, it was revolutionary. It was dangerous. The labor movement, spearheaded by groups like the Knights of Labor and later the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions, pushed for this breakdown of the day. They argued that a man who worked 14 hours a day was little more than a machine. He had no time to vote, no time to read, and no time to raise his children.

The Haymarket Affair in 1886 is the most famous—and tragic—turning point. Workers in Chicago went on strike demanding an eight-hour day. A bomb was thrown, police opened fire, and people died. The "invention" of our modern schedule was literally paid for in blood. It’s easy to forget that when we’re just annoyed by a Monday morning meeting.

Did Henry Ford Actually Invent the 40 Hour Work Week?

Kinda. But mostly no.

In 1926, Henry Ford did something that shocked the industrial world. He established a five-day, 40-hour work week for his factory workers without cutting their pay. This was a massive jump from the prevailing six-day schedule.

Why did he do it? It wasn't out of the goodness of his heart. Ford was a pragmatist. He realized two very specific things that changed the course of American capitalism:

- Burnout is expensive. Ford noticed that when men worked 60 hours a week, their productivity actually dropped. They made mistakes. They got hurt. By cutting the hours, he found that workers were more intense and focused during the time they were there.

- Workers need time to buy stuff. This is the big one. If your employees are working six or seven days a week, they don't have time to go on road trips. If they don't go on road trips, they don't need to buy a Model T. By giving them Saturday and Sunday off, Ford was essentially "creating" a consumer class.

He basically turned his employees into his best customers. It was a brilliant business move, but he was adopting a standard that labor unions had been screaming about for forty years. He didn't invent the concept; he proved it was profitable.

The Law Finally Catches Up

Even after Ford's big move, the 40-hour week wasn't "the law." Plenty of companies kept grinding their workers for 50 or 60 hours. It took the Great Depression to finally cement the 40-hour week into the American legal system.

Enter the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938.

During the Depression, unemployment was astronomical. The logic of the Roosevelt administration was basically: "If we make people work fewer hours, employers will have to hire more people to get the same amount of work done." It was a job-creation strategy.

The FLSA initially set the limit at 44 hours, then dropped it to 40 hours two years later. It also mandated time-and-a-half pay for anything over that limit. Suddenly, the 40-hour week wasn't just a "best practice" for car manufacturers; it was the law of the land. If you want to know who invented the 40 hour work week in a legal sense, look toward Frances Perkins. She was FDR’s Secretary of Labor and the first woman to hold a cabinet position. She was the powerhouse behind the FLSA and spent her life fighting for the protections we now take for granted.

The Myth of the "Standard" Week

We treat 40 hours like it's a scientific constant, like the speed of light or gravity. It's not.

In fact, the United States is one of the only "advanced" economies that doesn't have a federal law mandating a maximum work week length or a minimum amount of paid vacation. In many European countries, the "standard" is closer to 35 or 37 hours.

There's also the weird reality of the "white-collar" shift. The FLSA was designed for factory workers—people whose output is tied to time. If you’re on an assembly line, 40 hours of work equals a specific number of widgets. But if you’re a software engineer or a graphic designer, does "time" actually equal "value"?

Probably not.

Research from the University of Iceland and various trials in the UK have shown that a 32-hour work week (the four-day week) often results in the same—or higher—productivity. We are currently living in a world where the "40-hour" invention of 1926 is crashing into the digital reality of 2026.

Surprising Facts About Your Schedule

- The Weekend was a religious compromise. Saturday was added because Jewish workers needed the Sabbath off, and Christians wanted Sunday. Before the 40-hour week became standard, "Saint Monday" was a common tradition where workers would just... not show up on Mondays because they were hungover or tired from working through the weekend.

- Kellogg’s beat Ford to the punch. In 1930, W.K. Kellogg (the cereal guy) introduced a 30-hour work week at his plant in Battle Creek, Michigan. It was a huge success. Workers loved it, and productivity soared. It only reverted back to 40 hours during World War II because of labor shortages.

- The "Knowledge Worker" Trap. Many modern employees "work" 40 hours but are only productive for about three. The rest is spent on "performative work"—emails, meetings about meetings, and looking busy.

What This Means for You Right Now

Understanding who invented the 40 hour work week matters because it reminds us that the way we work is a choice, not a requirement of physics.

We are currently seeing a massive shift. The "Great Resignation" and the rise of remote work have reopened the debate that Frances Perkins and Henry Ford thought they settled a century ago.

If you feel like 40 hours is "too much," you aren't lazy. You're just living in a system designed for 1920s manufacturing while trying to navigate a 2020s digital economy. The 40-hour week was an incredible invention for its time—it saved lives and built the middle class—but it was never meant to be the final version of how humans spend their lives.

How to audit your own work life:

- Track your deep work. For one week, actually clock how many hours you are "producing" vs. "attending." You’ll likely find that your true 40-hour output happens in about 15 hours.

- Negotiate for results, not hours. If you’re in a position to do so, ask for a "results-only" evaluation. If the work is done in 30 hours, why stay for the extra 10?

- Study the 4-day week trials. Organizations like 4 Day Week Global provide data-backed resources you can bring to your HR department if you're looking to propose a pilot program.

- Recognize the "Overtime" trap. If you are consistently working 50+ hours, you are essentially giving your employer a 25% discount on your hourly rate.

The 40-hour week was a hard-won victory for the labor movement. It was a tool to stop exploitation. But as the nature of work changes, the "invention" needs an upgrade. Whether that means a 32-hour week or a total decoupling of time and pay, history shows us that the status quo only lasts until someone proves there's a more profitable, more human way to live.

Next Steps:

If you're interested in shifting your own schedule, start by documenting your "Value-to-Hour" ratio. Identify the tasks that generate 80% of your results and see if they can be condensed into a shorter window. The goal isn't just to work less, but to work with the same intentionality that Henry Ford saw in 1926—without the 1920s exhaustion.