You probably think of Carl Benz. Or maybe Henry Ford if you’re leaning into the American side of things. But honestly, if you're looking for one single person who invented internal combustion, you’re going to be disappointed. It didn't happen in a "Eureka!" moment in a clean lab. It was a centuries-long, often explosive, and frequently accidental series of failures involving gunpowder, turpentine, and a lot of frustrated Frenchmen.

The internal combustion engine wasn't born. It evolved.

It’s easy to point at a patent date and say, "There, that’s the start." But patents are just paperwork. Before the first piston ever successfully moved a wheel, there were decades of guys trying to figure out how to set things on fire inside a metal tube without blowing themselves up. Most of them failed. Some of them actually succeeded but had terrible marketing. It’s a story of geniuses who died broke and practical tinkerers who got rich by polishing other people's ideas.

The gunpowder phase and the guys you’ve never heard of

Long before gasoline was even a thing, people were obsessed with the idea of using vacuum and pressure. In the late 1600s, a Dutch polymath named Christiaan Huygens—a guy better known for clocks and Saturn’s rings—decided that gunpowder was the answer. He built a machine that used a small explosion to drive air out of a cylinder. When the air cooled, the resulting vacuum pulled a piston down. It worked, kinda. But it wasn't exactly practical for a commute. Using gunpowder to power a machine is basically like trying to use a hand grenade to open a door. It works, but it's a one-time trick that usually ends in a mess.

Then came the 1800s. This is where things get interesting and very French.

In 1807, Isaac de Rivaz, a Swiss inventor, actually built a vehicle powered by an internal combustion engine. He used a mixture of hydrogen and oxygen. It was bulky. It was slow. It was basically a giant cart with a bomb on the back. He’s technically a massive frontrunner for the title, but his design lacked the continuous cycle needed to make it useful. Around the same time, the Niépce brothers (who you might know from the invention of photography) were messing around with the Pyréolophore. This weird contraption used controlled dust explosions—literally Lycopodium powder—to power a boat. They got a patent from Napoleon Bonaparte himself.

Why we actually talk about Étienne Lenoir

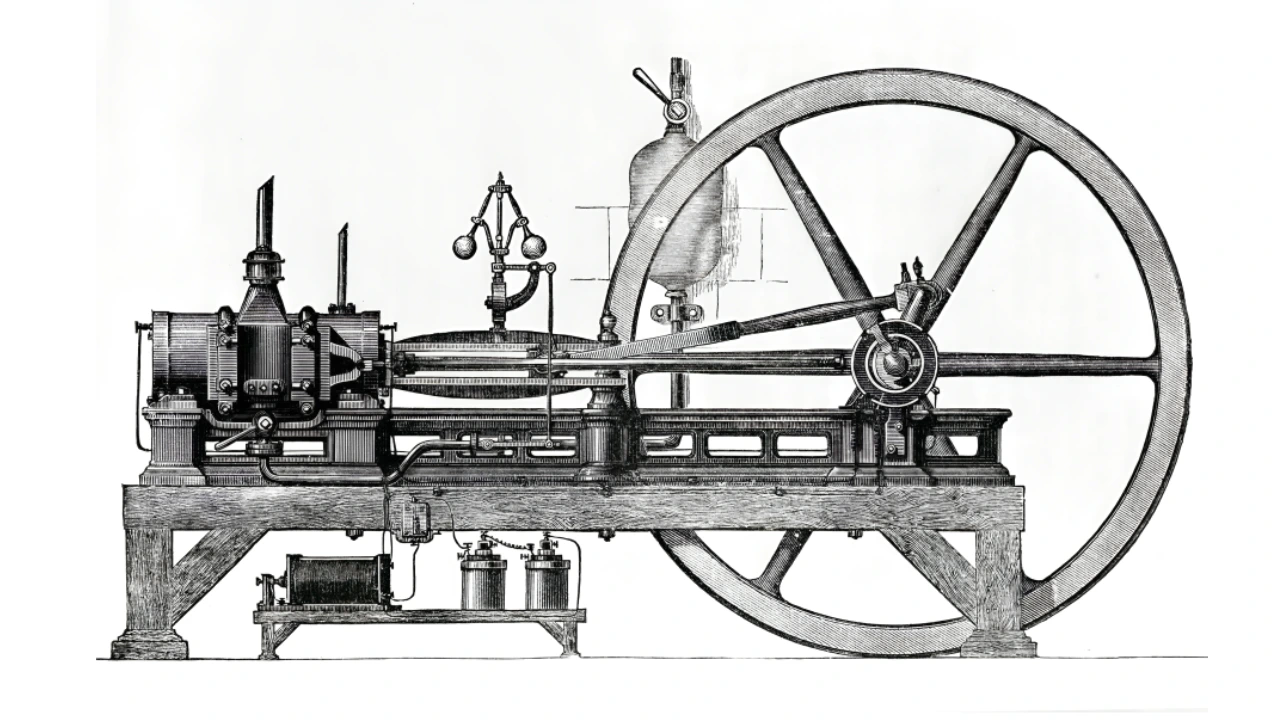

If we’re being real, the first "commercial" success happened in 1859. Jean Joseph Étienne Lenoir, a Belgian engineer living in Paris, finally created a gas-fired engine that didn't just explode once and quit. It used illuminating gas (the stuff used in streetlights) and looked a lot like a steam engine.

It was loud. It was incredibly inefficient. It wasted about 95% of the energy it created. But it sold.

Lenoir built about 400 or 500 of these things. People used them to power lathes and printing presses. He even stuck one on a "horseless carriage" and drove it from Paris to Joinville-le-Pont. It took three hours to go six miles. You could literally walk faster, and yet, this was the moment the world realized that steam engines—massive, heavy, coal-burning monsters—might actually have competition. Lenoir is the unsung hero here because he proved there was a market for this stuff. He didn't make it perfect, but he made it real.

The Nikolaus Otto breakthrough

While Lenoir was tinkering in France, a German traveling salesman named Nikolaus Otto saw one of those gas engines and thought he could do better. He was right. Otto is the reason your car doesn't sound like a rhythmic sneezing fit today. He realized that if you compressed the fuel-air mixture before you ignited it, you got a much bigger bang for your buck.

💡 You might also like: Can You See Who Looks at Your Pinterest? Why You Probably Can’t (But Should Care Anyway)

This led to the "Otto Cycle."

- Intake.

- Compression.

- Power.

- Exhaust.

The four-stroke engine. This is the DNA of almost every car on the road today. Otto’s 1876 engine was a massive leap forward. It was efficient enough to actually compete with steam. However, even Otto didn't see the full picture. He was focused on stationary engines for factories. He didn't think his engine was light enough or fast enough to power a vehicle. He was thinking big and heavy, while the world was about to move small and fast.

The lawsuit that almost changed history

Here’s a fun bit of legal drama: Otto didn't actually invent the four-stroke cycle. A Frenchman named Alphonse Beau de Rochas had already patented the theoretical concept in 1862. He just never built it. When Otto tried to defend his patents in court, the lawyers dug up de Rochas's old papers. Otto lost his patent protection in Germany in the 1880s. This was actually a huge win for humanity because it meant anyone could now build four-stroke engines without paying Otto a dime.

Enter Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach.

These two were former employees of Otto. They took the four-stroke design and obsessed over making it smaller. They wanted high-speed engines. They invented the "Grandfather Clock" engine and eventually the carburetor, which allowed for the use of liquid gasoline. Up until this point, most engines were running on gas piped in from the city. Liquid fuel meant portability. Portability meant freedom.

Benz, the finish line, and the woman who saved him

By 1886, Karl Benz had built the Patent-Motorwagen. It’s often cited as the first "true" automobile because he didn't just slap an engine on a carriage; he designed the whole thing as a single unit. It had three wheels, a steering tiller, and an engine that produced roughly 0.75 horsepower.

But nobody wanted to buy it.

Benz was a brilliant engineer but a bit of a perfectionist and a nervous marketer. The invention might have died in a workshop if it weren't for his wife, Bertha Benz. In 1888, without telling her husband, she took her two sons and drove the Motorwagen 60 miles to her mother’s house. She had to fix the fuel lines with her hatpin. She used her garter to insulate a wire. She even convinced a local cobbler to nail leather onto the brake blocks, essentially inventing brake pads.

That road trip proved to the world that the internal combustion engine wasn't just a toy for scientists. It was a tool for travel.

The Diesel detour

We can’t talk about who invented internal combustion without mentioning Rudolf Diesel. In the 1890s, he wanted to create an engine that was even more efficient than Otto's. He hated how much heat energy was wasted. His idea was "compression ignition"—squeezing air so hard it gets hot enough to ignite the fuel without a spark plug.

His first prototype exploded and nearly killed him.

Eventually, he made it work. Diesel engines were way more efficient, but they were heavy. For a long time, they were only used in ships and submarines. Rudolf himself had a tragic end; he disappeared off a steamship in the English Channel in 1913, just as his invention was starting to take over the industrial world. Some people think it was suicide; others think he was tossed overboard by competitors or government agents. It’s one of the great mysteries of the industrial age.

What we get wrong about the timeline

When you look back, the timeline is messy. It isn't a straight line.

- 1680: Huygens and his gunpowder vacuum.

- 1807: De Rivaz and his hydrogen cart.

- 1860: Lenoir makes the first "buyable" engine.

- 1876: Otto perfects the four-stroke cycle.

- 1885/86: Daimler and Benz turn the engine into a car.

- 1892: Diesel ups the efficiency game.

So, who invented it? If you have to pick one, Otto is the mechanical father, but Benz is the one who made it matter. But really, it was a collective effort of about twenty guys who were all obsessed with the same problem: how do we stop using horses?

Why this history matters right now

The internal combustion engine is currently in its twilight years as electric vehicles take over. But understanding its origin helps you realize that technology never happens in a vacuum. It took 200 years to get from gunpowder to the Ford Model T. We often think of tech as something that moves "fast," but the core of how we've moved around the planet for the last century was actually a very slow, very painful series of incremental gains.

📖 Related: 4.2 Divided by 10: Why This Tiny Calculation Trips People Up

It’s also a reminder that the person who gets the credit is usually the one who survives the longest or has the best business partner. Lenoir was first to market, but we don't drive "Lenoirs." We drive cars based on Otto's cycle because Otto’s team figured out how to make it reliable.

Practical takeaways and next steps

If you're a student, a car enthusiast, or just someone who likes winning trivia nights, keep these nuances in mind. The "who" is less important than the "how."

Track the evolution yourself

If you want to see these machines in person, don't just look at photos. The Smithsonian in D.C. has some of the earliest experimental engines. If you're in Europe, the Deutsches Museum in Munich is basically the holy grail of internal combustion history. Seeing an original Otto engine in person makes you realize how massive and terrifying these early machines actually were.

Research the "Missing" inventors

Look into Samuel Morey. He was an American who patented an internal combustion engine in 1826—long before the Germans. He even powered a boat on the Connecticut River. Why didn't he win the history books? Mostly bad luck and a lack of funding.

Understand the mechanical legacy

Next time you’re sitting at a red light, remember the "Four Strokes." Every time your engine revs, you're hearing the exact cycle Nikolaus Otto perfected in a workshop in 1876. We are still using his logic, even if the fuel is cleaner and the parts are made by robots.

The story of the internal combustion engine is ultimately a story of persistence. It wasn't about one genius. It was about a hundred people who were willing to get their hands dirty, fail publicly, and occasionally blow up their workshops until they finally figured out how to harness fire.