Ask a dozen historians who invented first computer and you’ll basically get a dozen different answers. It’s a total mess. People love a clean story where one genius shouts "Eureka!" in a dusty shed, but the reality of computing is a long, jagged line of failed experiments, massive government grants, and brilliant people who died long before their machines ever actually turned on.

If you're looking for a single name to put on a trivia card, you're going to be disappointed. Was it the guy who drew the blueprints in the 1800s? Was it the team that built a room-sized calculator to crack Nazi codes? Or maybe the guys who finally ditched the mechanical gears for vacuum tubes?

Honestly, the "first" depends entirely on how you define the word "computer." If you mean a machine that can do math, we’re looking at the 1600s. If you mean something you can actually program to do different tasks, that's a whole different century. Let's get into the weeds of who actually built the foundations of the world we live in today.

The Victorian Visionary: Charles Babbage

Most people start the clock with Charles Babbage. In the 1830s, this British mathematician designed something called the Analytical Engine. It’s wild to think about. He was trying to build a general-purpose, programmable computer using nothing but brass gears, steam, and punch cards.

It had a "mill" (a CPU) and a "store" (memory). It even had a way to loop instructions, which is the bread and butter of modern coding. But here's the catch: he never actually finished it. The British government eventually got tired of throwing money at his "Difference Engine" projects, and Babbage was known for being, frankly, a bit difficult to work with. He had the right idea—arguably the perfect idea—about a century too early.

We can't talk about Babbage without mentioning Ada Lovelace. She wasn't just some assistant; she saw what Babbage couldn't. While he was focused on numbers, she realized the machine could manipulate any symbol, even music or art. She wrote the first algorithm intended for a machine, making her the first programmer in history. If Babbage provided the hardware (in theory), Lovelace provided the soul.

The Secret War Hero: Alan Turing and Colossus

Fast forward to World War II. This is where things get fast and incredibly high-stakes. The British needed to crack the German "Tunny" cipher, which was way more complex than the famous Enigma.

Enter Tommy Flowers, a post office engineer who doesn't get nearly enough credit. Working at Bletchley Park, he built Colossus in 1943. This was the world’s first large-scale electronic digital "computer," though it was purpose-built for codebreaking rather than being a general machine you could use for anything.

It used 1,600 vacuum tubes. Think about that for a second. While Babbage was messing with gears, Flowers was using electricity. The problem with Colossus’s claim to being the "first" is that it was kept top secret for decades. After the war, Churchill ordered the machines destroyed. If the world had known about Colossus in 1945, the history books would look very different today.

Then there’s Alan Turing. He gave us the "Turing Machine" concept in 1936, which is essentially the logical blueprint for how all computers work. He proved that a machine could simulate any algorithmic logic. He’s the father of computer science, even if he didn’t physically solder the first circuit boards of the machines that eventually won the war.

The American Giant: ENIAC

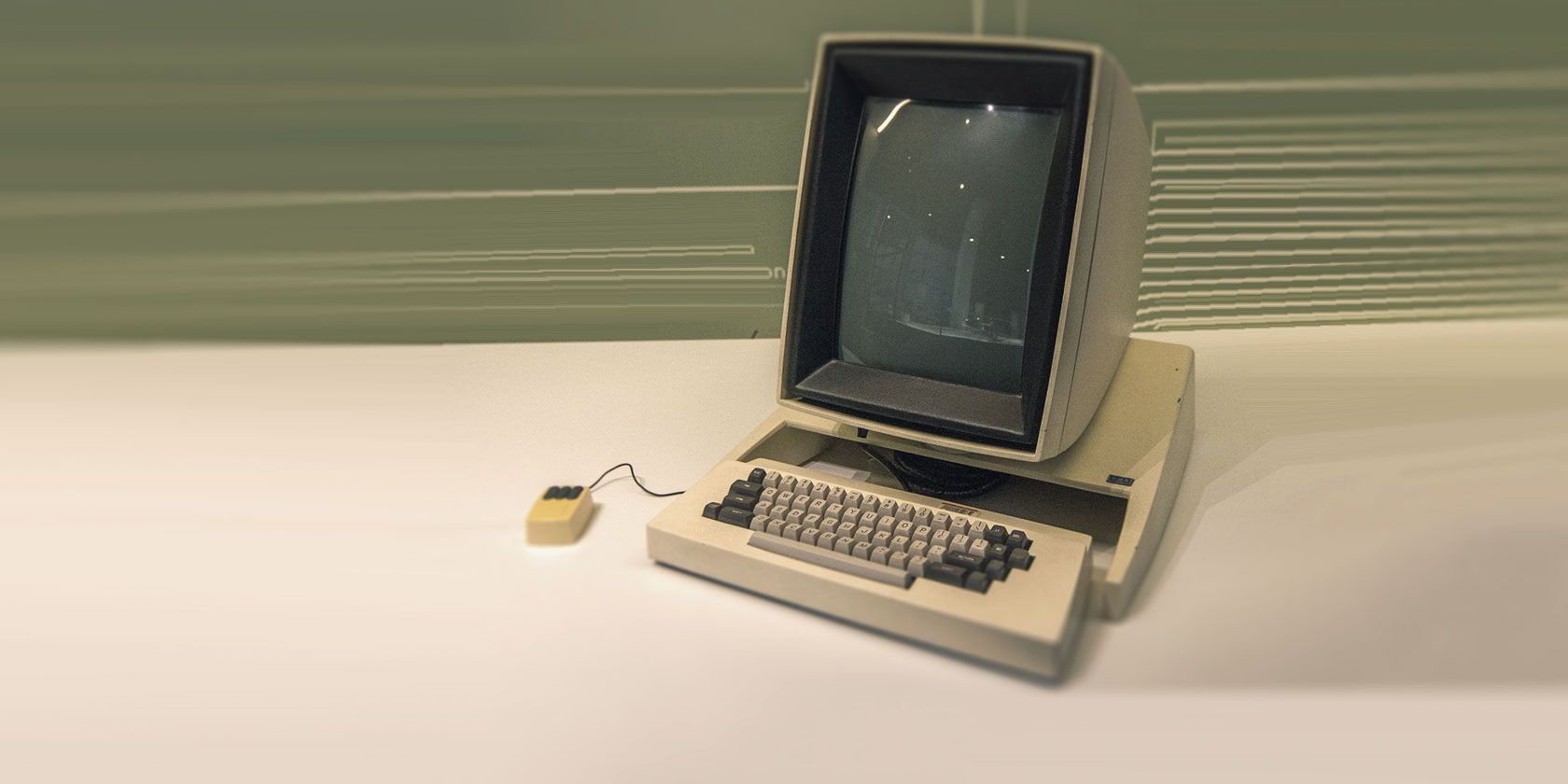

If you grew up in the US, you probably learned that J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly at the University of Pennsylvania are the ones who invented first computer. Their machine, the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer), was unveiled in 1946.

ENIAC was a beast.

It weighed 30 tons.

It took up a 30-by-50-foot room.

It used 18,000 vacuum tubes.

Supposedly, when they turned it on, the lights in Philadelphia dimmed. Unlike Colossus, ENIAC was "Turing complete," meaning it could be reprogrammed to solve a vast range of numerical problems. But "reprogramming" it didn't mean typing code. It meant a team of women—like Kathleen Antonelli and Jean Bartik—physically pulling cables and flipping switches for days at a time.

The Courtroom Twist: The Atanasoff-Berry Case

For a long time, Eckert and Mauchly held the patent for the electronic digital computer. But in 1973, a massive legal battle flipped everything on its head. A judge ruled that the ENIAC patent was invalid and that the "inventor" was actually a guy named John Vincent Atanasoff.

💡 You might also like: The wallpapers for ios 11 that changed how we look at our iPhones

Atanasoff, along with his student Clifford Berry, built the ABC (Atanasoff-Berry Computer) at Iowa State College between 1939 and 1942. It was small, but it was the first to use binary math (1s and 0s) and electronic switching. Mauchly had actually visited Atanasoff and seen his work before ENIAC was built.

The judge basically said that Mauchly "derived" the idea from Atanasoff. This is why, if you look at modern textbooks, the ABC is often cited as the first electronic digital computer, even though it wasn't programmable and it never really went into full operation like ENIAC did.

Konrad Zuse: The Forgotten German Genius

While the Brits and Americans were building machines for war, a German engineer named Konrad Zuse was working in his parents' living room. In 1941, he finished the Z3.

This was a massive achievement. The Z3 was the world’s first working, programmable, fully automatic digital computer. It used telephone relays instead of vacuum tubes, which made it slower than ENIAC, but it was arguably a more elegant design. Because it was developed in Nazi Germany, it remained isolated from the rest of the scientific world for years. Had Zuse had better funding or a different location, the computer revolution might have started in Berlin instead of Manchester or Philadelphia.

Making Sense of the Timeline

So, who wins? It really comes down to your criteria.

✨ Don't miss: What Would I Look Like as a Man? The Science and Tech Behind Gender Swapping

- First Design: Charles Babbage (1837)

- First Electronic Digital (Special Purpose): Tommy Flowers / Colossus (1943)

- First Programmable Digital: Konrad Zuse / Z3 (1941)

- First Binary Electronic (Small Scale): John Atanasoff / ABC (1942)

- First General-Purpose Electronic (Large Scale): Eckert & Mauchly / ENIAC (1945)

It's a relay race. No one person "invented" the computer. They all stood on each other's shoulders, sometimes without even knowing it because of wartime secrecy and slow communication.

Why This Matters Today

Understanding who invented first computer isn't just about trivia. It’s about recognizing that technology is iterative. We often give credit to the person who markets the product or the person who has the loudest patent lawyer, but the actual breakthroughs usually happen in quiet labs or living rooms years earlier.

If you're looking to apply this knowledge, here's the reality: innovation is rarely a solo act. If you're building a business or a new piece of tech, don't obsess over being the "first" in an absolute sense. Focus on being the first to make the technology useful and accessible. Babbage was a genius, but his machine didn't change the world because it didn't exist in a functional state. ENIAC changed the world because it actually crunched the numbers for the hydrogen bomb and weather patterns.

Actionable Takeaways for Modern Tech Enthusiasts

- Look for the "Unsung" Contributors: In any project, there is usually a "Tommy Flowers" figure—the person doing the technical heavy lifting while others get the headlines. If you're hiring or building a team, find those people.

- Binary is King: The shift from decimal (Babbage) to binary (Atanasoff/Zuse) was the real turning point. Simplicity in architecture usually wins in the long run.

- Documentation is Permanence: The reason we remember Babbage so well, despite him never finishing his machine, is that his notes and drawings were meticulous. If you have a groundbreaking idea, write it down in detail.

- Hardware vs. Software: Realize that the "computer" was just a shell until people like Ada Lovelace or the ENIAC programmers figured out how to make it do something. Logic is just as important as the physical machine.

The story of the first computer is a reminder that great things take time, a lot of money, and usually a few lawsuits to sort out. It’s a messy, human story, which makes it way more interesting than a simple name and date in a history book. Next time you pull your phone out of your pocket, remember it’s not just a descendant of Steve Jobs; it’s the great-great-grandchild of a 30-ton monster in Philadelphia and a bunch of brass gears that never quite turned.