You’d think a system that revolutionized literacy for millions would have been dreamed up by a panel of high-level scientists or some government committee with a massive budget. It wasn’t. It was actually a teenager. Louis Braille was just fifteen years old when he finalized the system we still use today. Imagine being a kid in the 1820s, living in a world that basically wrote off blind people as "unteachable," and deciding to reinvent the way the human eye—or rather, the human finger—processed language. It’s wild.

Louis wasn’t born blind. That’s a detail people often miss. He was born in 1809 in Coupvray, a small village near Paris. His dad was a leather maker. When Louis was three, he was messing around in his father’s workshop, trying to mimic the work he saw. He picked up an awl—a sharp, pointy tool used to punch holes in leather—and it slipped. It struck him in one eye. Infection set in, and back then, medical science was... well, let’s just say it wasn't great. The infection spread to his other eye. By age five, he was completely blind.

The Frustrating Reality of Early Literacy

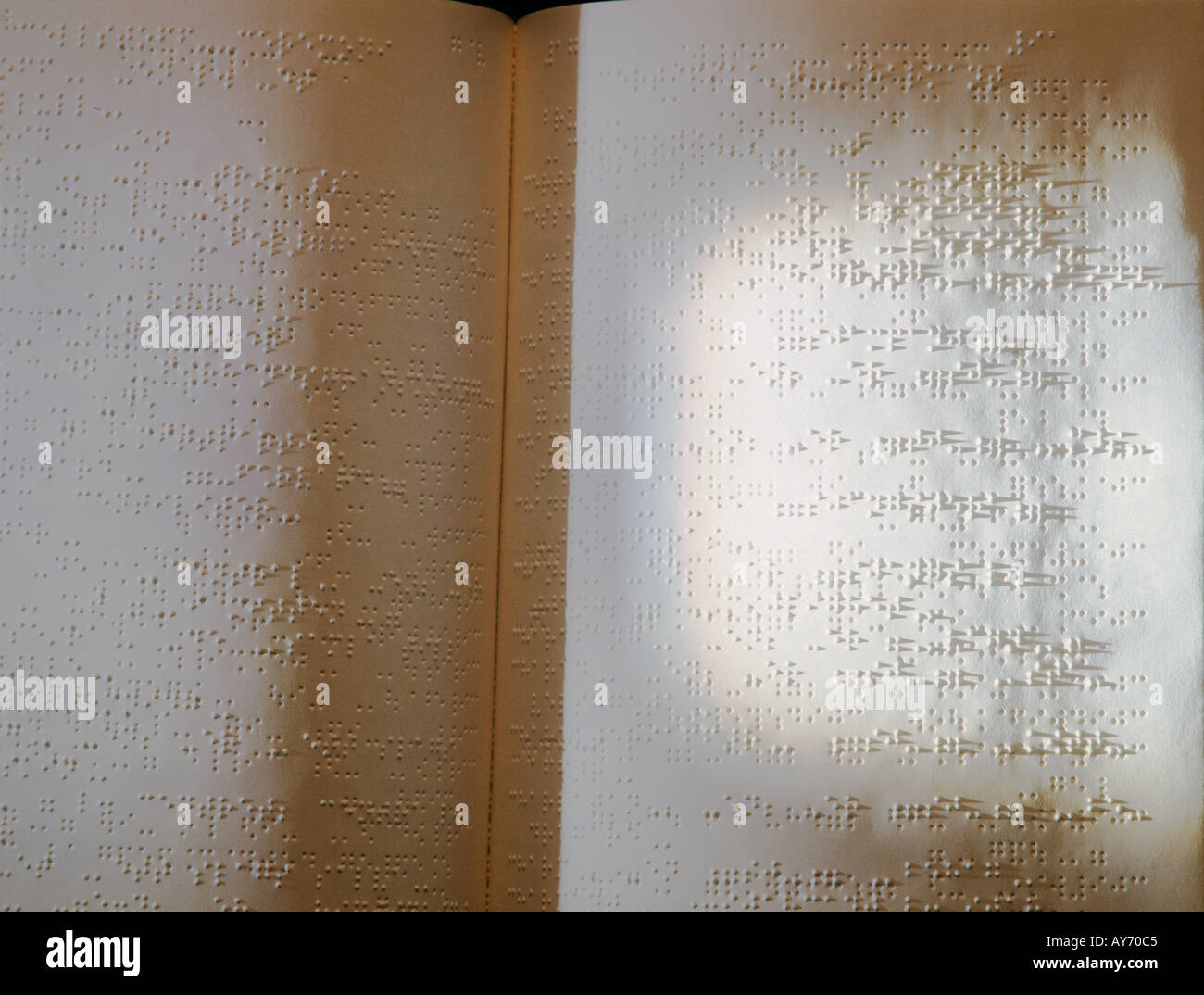

Before Louis came along, the options for blind students were honestly pretty depressing. He ended up at the Royal Institute for Blind Youth in Paris. It sounds fancy, right? It wasn't. The school was damp, the food was mediocre, and the teaching methods were incredibly clunky. They used something called the Haüy system. Basically, they took heavy paper and embossed the shapes of standard Latin letters onto it.

Can you imagine trying to read a whole novel by feeling the outline of a capital "R" or a "Q"? It took forever. The letters were huge. A single short story would require multiple heavy volumes. Plus, the students couldn't write back. They were passive consumers of information, trapped in a one-way street of learning. Louis hated it. He was a bright kid, a talented organist, and he wanted more than just "feeling" big, bulky letters that weren't designed for fingers in the first place.

🔗 Read more: How can I see my sons texts? A Parent’s Reality Check on Privacy and Safety

The Military Connection: "Night Writing"

The real turning point for who invented braille script didn't happen in a classroom. It happened because of the French military. A man named Charles Barbier, a captain in Napoleon’s army, showed up at the school with an invention he called "sonography" or "night writing."

Barbier’s goal wasn't actually to help the blind. He wanted a way for soldiers to share top-secret tactical information in the dark without lighting a lamp and getting shot by the enemy. His system used a 12-dot grid. It was phonetic, meaning it represented sounds rather than letters.

It was a total failure for the army. The soldiers found it way too complicated. But when Louis Braille saw it, he realized the potential. He saw the dots. He saw the raised bumps. But he also saw the flaws. A 12-dot grid is too big for a single fingertip to scan without moving. If you have to move your finger up and down just to recognize one character, you lose the flow of the sentence. Your brain forgets the beginning of the word by the time you reach the end.

How Louis Braille Fixed the System

Louis spent his nights poking holes in paper with his father’s awl—the very same tool that had blinded him. There’s a poetic irony in that, isn't there? Between the ages of 12 and 15, he hacked away at Barbier’s system.

He made two massive changes that changed everything:

- He shrunk the 12-dot grid down to 6 dots.

- He switched from phonetics (sounds) to an actual alphabet.

By shrinking the cell to two columns of three dots, he made it so the entire character fit under one stationary fingertip. That’s the "secret sauce." It allowed for "sight reading" with the fingers. By 1824, he had it. He had created a 63-combination code that included the alphabet, punctuation, and even mathematical symbols.

He didn't stop there. Later, he even figured out how to transcribe music. As an organist, he needed to read scores. So, he adapted his dot system to represent notes, accidentals, and timing. It was brilliant. It was elegant. And, predictably, the adults in charge initially hated it.

Why it Took So Long to Catch On

You’d think the school would have thrown him a parade. Nope. The teachers at the Royal Institute were actually afraid of Braille. Why? Because if blind students could read and write a code that sighted teachers couldn't understand, the teachers would lose control. They literally banned the script for a while. They forced students to keep using the old, bulky Haüy letters.

🔗 Read more: BHO Extraction: Why Hash Oil with Butane is Still the Industry Standard

But you can’t stop a good idea. The students loved it. They started learning it in secret, passing notes, and teaching each other. It was like an underground literacy movement. It wasn't until 1854—two years after Louis died of tuberculosis—that the school finally officially adopted the system. By the late 1800s, it was spreading across Europe. By 1932, a "Standard English Braille" was finally agreed upon between the US and the UK.

Braille in the Digital Age: Is it Still Relevant?

A lot of people ask me, "Hey, with screen readers and AI like Siri or Alexa, do we even need Braille anymore?"

Honestly, the answer is a resounding yes. Think about it this way: would you say sighted people don't need to learn to read because we have audiobooks? Of course not. Literacy isn't just about hearing information; it's about grammar, spelling, and the structure of language.

Studies from organizations like the National Federation of the Blind show a direct correlation between Braille literacy and employment. If you only rely on audio, you don't learn how a word is spelled. You don't "see" the punctuation. For a blind person, Braille is the difference between being "informed" and being "literate."

Today, technology has actually made Braille cooler. We have:

🔗 Read more: Apple Store Chula Vista: Why the Otay Ranch Spot Still Matters

- Refreshable Braille Displays: These are devices that connect to computers or phones. Small pins pop up and down to create Braille cells in real-time as you navigate a website.

- Braille Note-takers: Think of these as specialized tablets for the blind.

- Tactile Graphics: New printing tech allows for complex maps and diagrams to be rendered in raised dots.

What Most People Get Wrong About Braille

There are a few myths that just won't die. First, Braille is not a language. It’s a code. You can write English in Braille, but you can also write French, Spanish, Chinese, or Arabic. Every language has its own Braille adaptation.

Second, it’s not just for the "totally blind." Many people with low vision or progressive eye conditions use Braille to reduce eye strain or to read when lighting is poor.

Third, it’s not "hard" to learn compared to any other alphabet. Kids pick it up incredibly fast. The challenge is often the lack of teachers (called TVIs—Teachers of Students with Visual Impairments) and the high cost of Braille embossed books.

Actionable Insights and Next Steps

Understanding who invented braille script is more than just a history lesson; it’s about recognizing the importance of accessibility in design. If you’re looking to support literacy or learn more, here’s what you can actually do:

- Audit your surroundings: Look at the elevators, ATMs, and room signs in your office or apartment. Is there Braille? Is it damaged? Most people walk past it without ever noticing.

- Support Braille Libraries: Organizations like the National Library Service (NLS) for the Blind and Print Disabled provide free Braille books. They often need volunteers or advocacy.

- Explore "Unified English Braille" (UEB): If you're interested in the technical side, look up how the code was updated in 2016 to better handle web URLs and email addresses. It’s a fascinating look at how a 200-year-old system evolves for the internet.

- Consider Universal Design: If you're a business owner or a creator, think about how your "physical" or "digital" products can be felt, not just seen.

Louis Braille didn't just invent a code; he handed people a key to a door that had been locked for centuries. He proved that a teenager with a leather-working tool and a lot of persistence could literally change the way the world "sees." By focusing on the user (the finger) rather than the tradition (the eye), he created one of the most successful pieces of user-interface technology in human history.