Ask anyone on the street who invented airplanes first and they’ll give you the same two names. Orville and Wilbur Wright. It’s the standard answer in every history textbook from Ohio to Tokyo. But if you head down to São Paulo, Brazil, you’re going to get a very different answer: Alberto Santos-Dumont.

History is messy.

The truth is that the "first" airplane depends entirely on how you define the word "airplane." Are we talking about the first thing to leave the ground? The first thing to stay up for more than a few seconds? Or the first machine that could actually take off under its own power without a giant catapult?

When you dig into the archives of the early 1900s, you realize the Wright brothers weren't working in a vacuum. They were part of a global, frantic, and often dangerous race to conquer the sky.

The December Day in North Carolina

On December 17, 1903, at Kitty Hawk, the Wright brothers made history. Or did they?

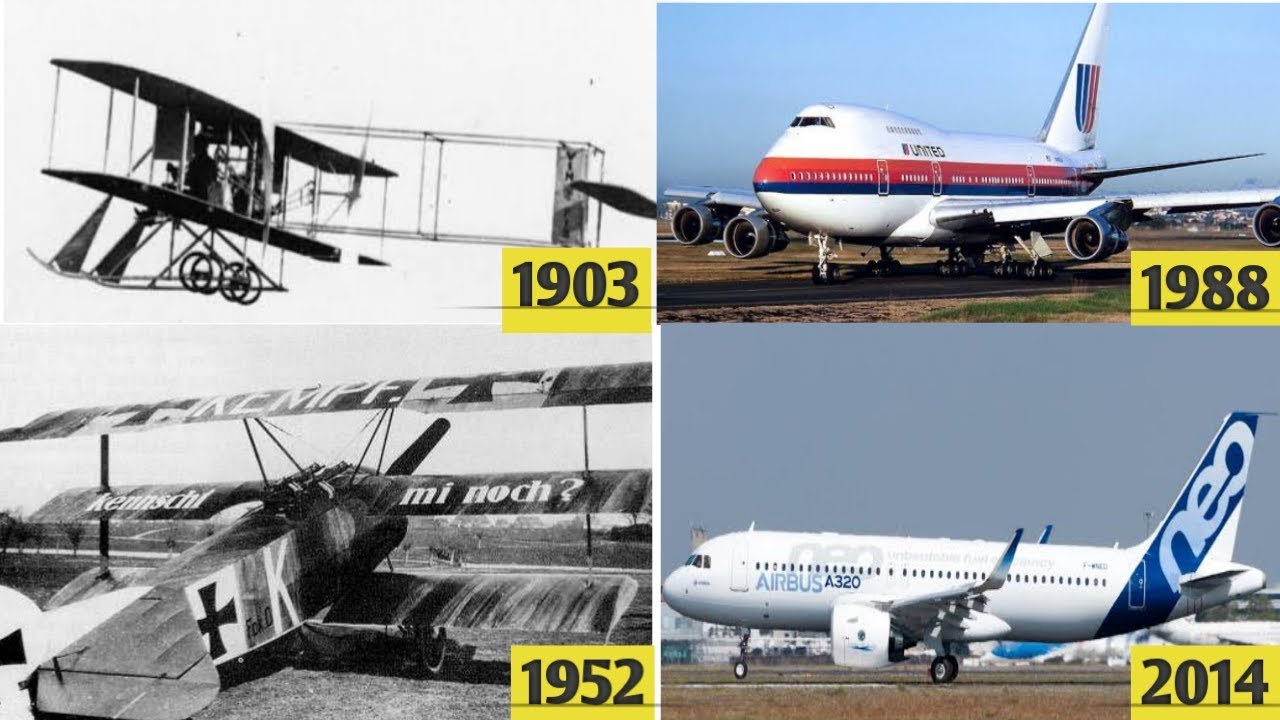

Orville took the controls of the Wright Flyer and stayed in the air for 12 seconds. He traveled 120 feet. That is shorter than the wingspan of a modern Boeing 747. It was clumsy. It was shaky. But it was controlled.

Later that day, Wilbur managed a flight of 852 feet, staying aloft for nearly a minute. This is the moment most historians point to as the definitive "first." They used a gasoline engine and a sophisticated system of "wing-warping" to tilt the aircraft. This was their secret sauce—lateral control.

But there’s a catch that critics always bring up.

📖 Related: World Travel Adapter Kit Apple: Why This $29 Accessory Still Beats Cheap Knockoffs

The Wrights used a rail system and a weight-drop catapult to help get their machine into the air. In the eyes of many Europeans at the time, if you needed a "kick" to get up, you weren't truly flying. You were just an advanced glider with a motor.

Alberto Santos-Dumont and the Brazilian Claim

Enter Alberto Santos-Dumont. He was a dapper, eccentric Brazilian living in Paris. He wore high collars and flew his personal dirigibles to dinner parties, tying them to lampposts. He was the world's first true celebrity aviator.

In 1906, three years after Kitty Hawk, Santos-Dumont flew his "14-bis" aircraft in front of a massive crowd in Paris.

This is the big distinction.

Unlike the Wright brothers, who were notoriously secretive and flew in a remote corner of North Carolina with few witnesses, Santos-Dumont did it in public. More importantly, the 14-bis took off under its own power using wheels. No rails. No catapults. No headwinds required.

For the Aero-Club de France, this was the first "real" flight because it met the strict criteria of unassisted takeoff. If you go to Brazil today, Santos-Dumont is the undisputed Father of Aviation. The Wright brothers? They’re often viewed as clever tinkerers who used a slingshot to get a head start.

The Forgotten Pioneers Who Came Close

It’s a mistake to think it was just a two-way race.

Samuel Langley, the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, was the "official" favorite to win the race. He had massive government funding. His "Aerodrome" was a serious piece of machinery. However, he tried to launch it from a houseboat on the Potomac River twice in late 1903. Both times, it crumbled and fell into the water like a wet cardboard box.

Then there’s Gustave Whitehead.

Some researchers in Connecticut swear that Whitehead flew a powered, bird-like machine called "No. 21" in August 1901—two years before the Wrights. The evidence? A newspaper report from the Bridgeport Herald. There are no clear photos of the flight, only blurry images of the plane on the ground. Most mainstream historians at the Smithsonian dismiss Whitehead's claim, but the debate is so heated that it actually led to legal disputes over museum contracts.

And we can't forget Richard Pearse.

A lonely farmer in New Zealand, Pearse supposedly flew a monoplane of his own design in March 1903. His plane was incredibly prophetic. It had a tricycle landing gear and a steerable nose wheel. But Pearse himself was humble—maybe too humble. He later admitted his flights weren't "controlled" in the way the Wrights' were. He mostly just crashed into his own hedge.

Why the Wright Brothers Usually Win the Debate

So, why do the Wrights get the crown?

It’s not just because they were first. It’s because they solved the physics of flight better than anyone else.

Before the Wrights, most people thought of flying like driving a car. You turn left, you go left. But flying happens in three dimensions. You have pitch (up and down), yaw (left and right), and roll (leaning side to side).

The Wright brothers realized that to turn an airplane, you have to bank it, like a bicycle. Their "wing-warping" technique allowed them to manipulate the lift on each wing. This made their aircraft a true vehicle, not just a projectile. While Santos-Dumont's 14-bis was essentially a series of box kites strapped together, the Wright Flyer was a masterpiece of aerodynamic engineering.

They also built their own engine. When no car manufacturer could provide a motor light enough and powerful enough, they built a four-cylinder aluminum block engine from scratch in their bicycle shop. That's some serious grit.

The Controversy of the Smithsonian Agreement

Here is a bit of "inside baseball" that most people don't know.

For decades, there was a massive feud between the Wright family and the Smithsonian Institution. The Smithsonian originally claimed their former boss, Samuel Langley, had built the first machine "capable" of flight.

Orville Wright was so furious that he sent the original 1903 Flyer to a museum in London. He refused to bring it back to America unless the Smithsonian admitted the Wrights were first.

In 1948, a contract was finally signed. The Smithsonian got the Flyer, but only on the condition that they always label the Wrights as the first to fly. If they ever recognize anyone else—like Whitehead or Santos-Dumont—the Wright heirs can take the plane back.

This contract is why some skeptics think the "official" history is a bit rigged. It’s a legal requirement to say the Wrights were first if you want to display the world’s most famous airplane.

How to Decipher History for Yourself

When you're trying to figure out who invented airplanes first, you have to look at the milestones rather than a single "Eureka" moment.

- Sir George Cayley (1804-1850): He’s the guy who actually figured out the four forces of flight (lift, weight, thrust, and drag). He’s the "Grandfather of Aviation."

- Otto Lilienthal: The "Glider King." He proved that human flight was possible if you understood the shape of the wing. He died in a crash, famously saying, "Sacrifices must be made."

- The Wrights (1903): First controlled, sustained, powered flight.

- Santos-Dumont (1906): First public, unassisted takeoff flight.

The reality is that aviation wasn't "invented" by one person. It was a cumulative effort. The Wrights were the first to put the whole puzzle together into a package that actually worked reliably.

Actionable Steps for Aviation Buffs

If you want to really understand this history beyond a Wikipedia summary, here is what you should do next:

- Check out the "Aviation Museum of New Hampshire" or the "Wright Brothers National Memorial": Seeing the actual scale of these machines changes your perspective. The 1903 Flyer is surprisingly flimsy-looking in person.

- Read "The Wright Brothers" by David McCullough: It’s the definitive biography and uses their actual letters to show how much they struggled with the "inventor" label.

- Research the "Pre-Wright" era: Look up Octave Chanute. He was the mentor to the Wright brothers and the "hub" through which all aviation knowledge flowed in the 1890s.

- Visit the Smithsonian's website: Look specifically for the "Whitehead Controversy" articles to see how they defend their position against recent claims.

Aviation history isn't a closed book. While the Wrights have the trophy, the story is big enough to include the eccentric Brazilians, the New Zealand farmers, and the German glider kings who all risked their lives to get us off the ground.